Disc Reviews

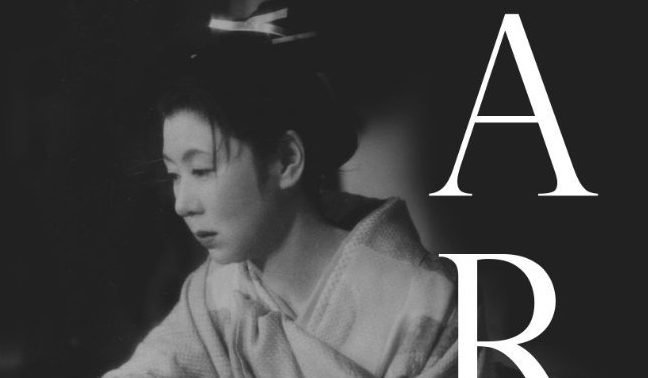

The Life of Oharu (1952) Blu-ray Review

Kenji Mizoguchi’s The Life of Oharu (1952) perhaps should have been expanded to the title ‘The Tragic Life of Oharu’. Based off a novel by Ihara Saikaku, ‘The Life of an Amorous Woman’ (written in 1686), the harsh injustice that society metes out to women historically demonstrates its universality. In the West there are many well known examples of how women have to conform to society’s rules or face alienation, whether it is the novels of Jane Austen, George Eliot, the Brontes or Flaubert’s ‘Madame Bovary’.

Set in the late 17th century, the films opens with a street walker, approximately in her late 40s complaining about how slow business is to the other ‘courtesans’. She finds herself in a temple and looks at little statues of figures. Her memory is cast back to when she was younger as the face of the statuette takes on the appearance of a lover from her past. Her memory flashes back to when she was in her 20s and the tragic circumstances of how her life has gone from being a lady courtier to prostitute. She recalls when she was primed to be married to a Lord but is instead swept off her feet by Katsunosuke, a man said to be beneath her station ( he is played by Akira Kurosawa regular, Toshiro Mifune in his only film for Mizoguchi). The couple fall in love, but their relationship is doomed and they are arrested simply due to his lowly status as a servant. Oharu and her parents are banished forever from the city and he is beheaded for his ‘crime’. Oharu is devastated once she learns of his death while her father is deeply ashamed and beats Oharu. One day while living in banishment in the country she is approached by a member of the court of Lord Matsudaira who has very strict and fussy instructions to find the perfect woman to bear a child. Oharu fits the bill and she reluctantly goes pleasing her father again. After some time she does bare him a son and is once again happy now she has her baby. In no time the baby is taken off her and she is once again banished having fulfilled her duty. Her life takes other twists and turns, ending up becoming a prostitute. Later she tries to escape from this period in her life, but her past constantly comes back to haunt her, causing her to be castigated by society. She even finds further brief happiness when she is married briefly to a small-time textile tradesman, but tragically he is murdered, once again landing her in poverty and a further fall from grace.

The common thread running through Mizoguchi’s films, the best known of which are his post-war films, are about the struggles of women, this being one of his best examples. In that sense it can very much be classified as a women’s film or melodrama. Mizoguchi himself was something of a rebel and the film faced some censhorship scrutiny, while the adaptation was of a notorious Japanese novel. However, probably for censorship reasons the suggested high appetite for sex in Saikaku’s novel gives way to a woman who works as a prostitute out of necessity, giving the film more power. While The Life of Oharu is clearly talking about a society 250-300 years earlier, it also makes some sided comments about the way society views women in post-war Japan, even then far from being an emancipated society and one built on patriarchal dominance. In many ways contemporaries such as Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse firmly set their films in contemporary Japanese society they only brushed the hardships portrayed in films like The Life of Oharu. Setting most of his films in an older period allowed Mizoguchi to be able to present more controvertial themes.

The framing of Mizoguchi’s films such as this one show an influence of classic Japanese floating art prints (after all he had also made Utamaro and His Five Women, 1946 about the famous Japanese printmaker). The American occupiers in Japan at the time both frowned on the Japanese nationalism of his films as well as approving of the more liberal emancipation themes. It was said that the director was a lover of women and his films certainly underscore this, as well as his sympathy and understanding in the way he portrayed prostitutes and courtesans, based, it is said the personal experience of people he knew. Extras on the disc are not as plentiful as on other Criterion Collection releases but are of high quality; ‘Mizoguchi’s Art and the Demimonde’ is an illustrated audio essay by Dudley Andrew that gives some great context, while the documentary, ‘Kinuyo Tanaka’s New Departure’ follows the actress’s cultural tour of the United States after the war in 1949 and how she was popularly received in post-war America.

This is an excellent introductory film to the career of Kenji Mizoguchi.

Chris Hick