Disc Reviews

Woodfall: A Revolution in British Cinema Box-Set

The latest release by BFI is a box-set collection, a 9 disc, 7 film collection that should be seen as a celebration, a celebration of some of the greatest films in British cinema history. Woodfall may not have the same household name as Ealing, Hammer or even the Rank Organization it so deserves, but the films themselves are true unchallenged classics and also provides a few surprises. Woodfall Film Production was a studio formed in 1958 by Tony Richardson, playwright John Osbourne and producer Harry Saltzman. Saltzman would not long after become the producer for most of the James Bond films up to The Spy Who Loved Me (1977).

The earliest film in the collection is the studio’s first film, Look Back in Anger (1959), adapted by Nigel Kneale (the Quatermass creator) and Osbourne himself. The story is the classic angry young man tale. Jimmy Porter (Richard Burton) lives in an attic bedsit with his best friend Cliff (Gary Raymond) and his wife, Alison (Mary Ure). Although he loves Alison, angry Jimmy is also underwhelmed by their relationship. He is clearly intelligent, plays trumpet in a jazz club, but is also a drifter with a chip on his shoulder. When Alison’s best friend, the posh Helena (Claire Bloom) shows up, this proves to be more than Jimmy can take.

Next is The Entertainer (1960), in which Laurence Olivier plays Archie Rice, a has been music-hall star on the Morecambe sea-front who still thinks he’s a hit with the ladies and still dreams of stage success. Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (also 1960) is one of the greatest of all British films and saw a new star in Albert Finney (who had also appeared briefly in The Entertainer). Finney stars as the brash and arrogant working-class machine engineer, Arthur Seaton who likes to get drunk at weekends and is having an unashamed affair with the wife (Rachel Roberts) of one of his colleagues. Until he gets her pregnant that is. Finney would star again in one of the most unusual and different films in the set in that it was in colour and based off the 18th century novel by Henry Fielding, the hugely successful Tom Jones (1963). Directed by Richardson, he was always a director looking forward and bought much of the bawdy style of Fielding’s novel to the screen.

A Taste of Honey (1961), a personal fave broke all sorts of taboos. Set in Manchester and Salford, it stars Dora Bryan as a brassy single parent who is more interested in getting married to the glass-eyed spivvy (Robert Stephens) than the well being of her 16-year-old daughter, Jo (Rita Tushingham). Jo has a brief fling with a black sailor whom she falls pregnant by and sets up home with the lonely and gay Geoffrey (Murray Melvin). Again, it is based off a play, this time by Shelagh Delaney and with a tragi-comic script it deals with its subject matter very sensitively.

Two more films in the set starred Tushingham: the Dublin set Girl with the Green Eyes (1964) about a young innocent Catholic girl who has an affair with a married man (Peter Finch) and the classic ’60s Swinging London movie, The Knack …And How to Get It (1965) in which Tushingham (again) plays an innocent who arrives in London where she winds up being caught between ladies man Ray Brooks and the sexually inexperienced character played by Michael Crawford.

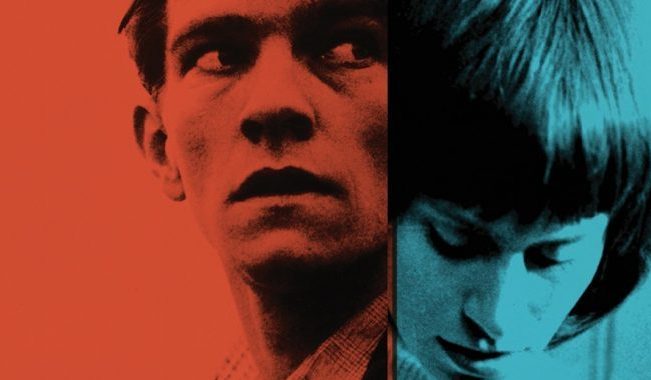

The other film in the set is The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962) which stars Tom Courtenay in another powerful role as the inmate of a young offendors institution who faces ridicule but competes in a long distance run. This and all the films here give a slice of life hitherto unseen in this country. True, that Ealing had often portrayed regional types in their film, the little man against big government and big business, while the Rank Organization were also not afraid to show the underclass in post-war society, but often those in charge spoke with plummy British accents. In these so-called Kitchen Sink dramas we saw a darker side of everyday life and Richardson et al were not afraid to tackle subjects as wide ranging as mixed-race relationships, homosexuality, abortion, sex out of wedlock and rape with an everydayness hitherto unseen. Much of this was helped by Walter Lassally’s camerawork and in most cases the stark nocturnal and urban camerawork.

The collection is absolutely laced with extras too numerous to mention, including interviews with the cast and crew from the films, both recent and vintage, Reisz’s celebrated documentary, We Are the Lambeth Boys (1959) about Teds in South London among other shorts. Elsewhere there is footage dating from 1901 of the Morecambe seafront, short films and stage versions of some of the adapted plays. The quality of the images on Blu-ray are outstanding of some of the greatest and most earnest and honest films to emerge from this country.

Chris Hick