High Noon (1952) Blu-ray Review

“A man’s gotta do, what a man’s gotta do…” is a phrase that’s acredited to many Westerns, usually ones connected to John Wayne, whether it is Stagecoach (1939) or Hondo (1953). These are false attributions, as it is also to attribute it to High Noon (1952). Nevertheless, it would be a quote that would perfectly fit this classic psychological Western. In the guise of the town marshal, Gary Cooper’s character of Will Kane is iconic, stoic and human in this, one of the actor’s strongest performances. However, Cooper’s humanity in this role led to much criticism as well as criticism for screenwriter Carl Foreman, a writer who was blacklisted in Hollywood during the anti-communist witch hunts. All this forms a part of the background to High Noon and goes someway towards highlighting what a great film this is. It is a role that is associated with Cooper which, along with Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Sergeant York (1941) is hard to separate from Cooper. Ironic then that he was far from the first choice, having been turned down by John Wayne among others.

The plot is fairly straight forward and standard, hardly surprising given that it is based off a short story, ‘The Tin Star’ by John W. Cunningham printed in a Western anthology magazine. But in the hands of Foreman and ultimately director Fred Zinnemann’s, the story is made into an absolute classic. It opens with the wedding between the town marshal Will Kane (Cooper) and his quaker bride, Amy (played by newcomer, Grace Kelly) in the small town of Hadleyville. The time is 10:35 in the morning and all the townsfolk appear to be enjoying the happy occasion. They leave on a buggy for their honeymoon when Kane learns that Frank Miller, an ex-con outlaw caught by Kane years ago is returning on the noon train. On the way out of town Kane is troubled and decides to go back and face his troubles rather than be constantly on the run, much to Amy’s chagrin. Because of her religious beliefs, she threatens to leave him on the noon train if he stays, the very train Miller is due in on. Kane believes that he has support from the town and can face down Miller and his gang. He soon learns that everyone from his deputy to the churchgoers and his former posse refuse to help him, finding himself alone and against the odds.

The term High Noon has of course become a metaphor for a showdown thanks to this film, demonstrating how important it is. On an extra on the disc, one of the film’s fans, Bill Clinton states this and can relate to Kane’s ordeal. Yet at the time of its release and depsite its Academy Awards the film was heavily frowned upon, in part because of its black listed writer (who Cooper defended to the hilt) to the false representation of the marshal as a coward as had been suggested by John Wayne and Howard Hawks (between them they made Rio Bravo, 1959 in response). Many Western purists found it had to believe that a marshal would be afraid of his duty (which Kane clearly overcomes and faces up to) or the representation of the townsfolk as cowards, which many saw as un-American or a metaphor for the communist witch hunts taking place in America.

Credit on the film should also be given to the incredible editing, not to mention the flat and stark cinematography by Floyd Crosby, father of folk star, Dave Crosby. Thanks to these elements, as well as Zinnemann’s economic and tight direction the film comes together perfectly for one of the greatest Westerns of all time. Add to this, there is the extraordinary performances by the characters actors, such as a young Lloyd Bridges as the cowardly deputy or Lon Chaney Jr. as the retired arthritc former town marshal. There is also a couple of great female co-performers, not least of all a young Grace Kelly, this being only a 2nd role as Kane’s Quaker bride. One performance often overlook is that of Mexican actress, Katy Jurado, adding a racial element into the film, that stands out as a strong woman in which her strong character breaks the stereotyped role of a beautiful Mexican woman.

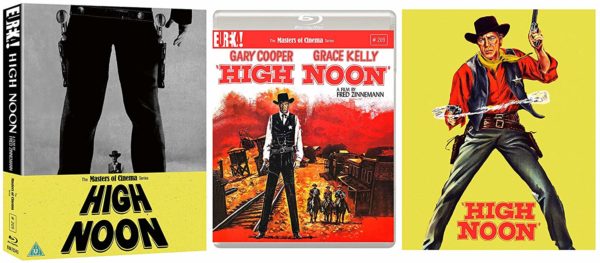

This package by Eureka in their Masters of Cinema label is exceptional. As well as a wonderful 100 page booklet, there are also a whole bunch of featurettes, some new, others old, including an appreciation by critic Neil Sinyard, a regular contributor to Eureka! (Sinyard had also written by biography on Zinnemann). There are also commentaries on the film by Glenn Frankel (who has also written on the film) and Stephen Prince.

Chris Hick