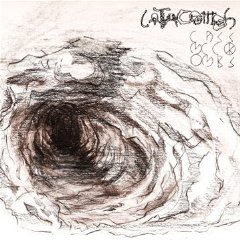

Cass McCombs – Catacombs

Catacombs is a puzzling piece of genre-defying semi-acoustica, with its familiar light and prettiness carries within itself the shades of something darker, knottier, at odds with itself to often productive effect. To start with the name itself, Catacombs is a deliberately eerie title for such a wistful sounding album on cursory listening. Essentially a singer-songwriter LP, its harmonies vary between The Beatles, Eagles, Ewan McColl and Lyle Lovatt, it’s all sighing steel pedals and sighing vocals alike. With a Willie Nelson meets Willie Mason sound then McComb’s debut enters an overloaded zone of troubadours whose product wavers between the affecting and the indulgent by its nearness to confessional and emotional expunging.

It takes a certain kind of artist just to transcend their material; create mood rather than either reducing tumults to a prosaic ‘I love you babe’ or something so personal its uselessly esoteric. Being a country album, it’s also almost natural that Combes’s debut veers towards the artificial and theatrical- towards other people’s voices in his titles– ‘lionkiller’, ‘executioner’ ‘sister bride’. Country has always relied– in it’s purest forms– on the old standards; just like the standard melodies and sounds associated with the genre, whether blue-grass or americana traditional images of prospectors and surviving prairies wives form the basis of its mythologies at most in modernised forms. Hence it begins with an ode to the siren girl of a thousand faces; romantic archetype or closet chauvinism, –debates rage– but he sounds at least impassioned in believing, until you hear the same modulations of pleading attached to his characters, to praising his ‘executioner’ job or lamenting absence from distant shores somewhere in a never-never-world underground in the ‘catacombs’. Like a countrified Bright Eyes, he can channel or mimic earnestness without being too scabrulous in his real disaffection- even the harsher moments are lyric.

Catacomb’s not just sonically country either but alt-country; full of experimental textures utilised by everyone from Wilco to Jace Evertett (he of ‘Bad Things’-theme to ‘True Blood’ semi-fame) , then transposed into a Celt-inflected mountainscape. Initially he sounds lorn, then on ‘Lost’ a sparse keyboard bass cranks up a kind of vaguely sensual tension beneath the clip-clop wood-block beats and sixties harmonics ending in a nebulously troubling electronic was. The same with ‘Harmonia’ later on the album, slide guitar cooing discovering chords which dig into nerves and move tear-strings yet with a dab of futurism sprinkled over all that dust-coated organic reminiscent of Geoff Barrow’s Portishead work or Danger Mouse on Joker’s Daughter’s electro-folk. Hence the album represents a tricksier but more interesting, should you wish to disappear into its world, proposition -made from pieces of the musical landscape and cult-culture around it, in an album which persuades you more of your own happiness faced with its art than of Cass’s sincerity in literal terms.

‘Executioner Song’ epitomises the disquieting lo-fi faux-naivety and the subtexts flowing through the work- occasionally moving into the Fairport Convention/1969 Bowie lilts across the its sparse-wooded hill images and underhanded confessional tone. An off-kilter tone none more so realised than towards the second half of the LP. ‘Sister, My Spouse’ with its ‘candle’ and ‘incestuous metaphors/anecdotes veers between fantastic wordplay and faintly disturbing naked invocations all delivered in Combe’s airy tremulous pitch. A pitch occasionally sliding without premonition into high-notes evoking the ‘spouse’ of its imagined dialogue within, like a disturbed fairytale or reptressed folk song from a time when civilisation hadn’t yet been forged.

‘Lionkiller got Married’, with its strange associations, also sums up the ever-more outré genre-bending juxtapositions fused with traditional songwriting nous. With its third-chord palm-muted build up fixed to salvation army trumpets, evoking 1968 lennon-esque surrealism with its deferred climax and tips to blues-rock laments whilst underpinned by soft organ drones. Its wooziness somnambulistic tone flows into the White Album piano of ‘Eavesdropping’, which revisits the mandolins and country violins. There’s indeed a east-european cracked-waltz vein running through at least four of these tracks, the sound of drink-saddened companions of flesh or ghost around him in this celebration of fine melancholy and indication of ‘Catacomb’s scope.

Penultimate cut ‘Jonesey Boy’ is a one of those minor key elegies- calling out to a kindred soul lost in one of life’ accidents, but with its familiar stymied boogie and a dream paced r n b Cas displaying more animated vocals, sounds impressively like our singer fighting a way out of his own haziness. All which would be a gently contrary to end this intriguing set of personal accounts and genre role-plays.

With an album which starts with laments to the impossible, and names itself after signs of loss, it cant all be joys though. And occasionally the record moves too much into pale-blooded woolly territory where the low-mixed words, however strange, can’t quite save it from inertia; the climactic ‘One way to go’ is a pall, locked in a recidivist mule-trot and larrisitude lyrics which would slip in seamlessly as a respite to the more intensive mid-album sections but comes across here as an afterthought, stretching the LP three minutes beyond a quietly triumphant sequencing.

Still, this is a hugely promising set from a composer with an instinctive feel for what makes his genre-splicing so special at the organic level.