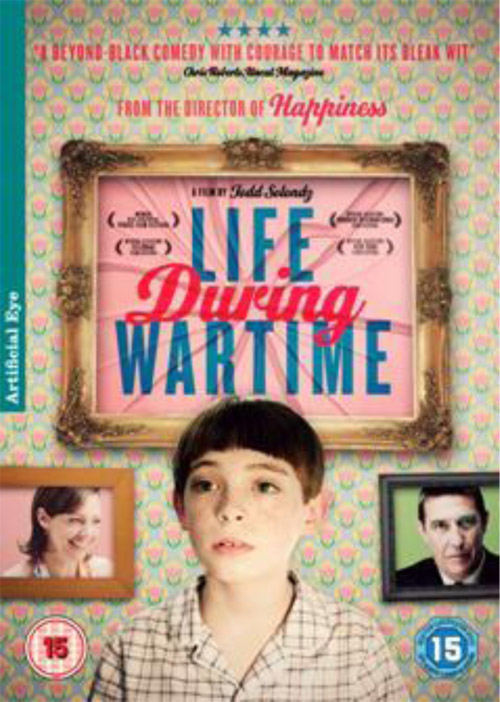

Life During Wartime –

Films that set out to expose and explore the murky flipside of American suburbia practically warrant their own genre, and Todd Solondz’s Happiness might be the bleakest of the lot. His sophomore effort divided opinion sharply in 1998: it’s either a brilliant, daring black comedy or unwatchable filth depending on who you ask. This sequel, bafflingly featuring an entirely new cast, catches up with the characters from the first film twelve years on.

There’s Trish (Allison Janney), a middle-aged housewife now looking for love and trying to hide the truth about her recently-released-from-prison paedophile husband – portrayed with brooding gusto this time by Ciaran Hinds – from her 12-year old son. There’s the brilliantly successful but profoundly discontent Helen (Ally Sheedy), now living in estrangement on the other side of the continent, and there’s Joy (Shirley Henderson), a put-upon musician with a tragic past and failing marriage, who has returned home to mull things over.

The film is essentially a jumpy sequence of artfully shot set-pieces, following various narrative, the most compelling of which is Hinds’ progress on leaving prison, drawn towards his eldest son – now a somewhat messed-up college student – apparently in search of forgiveness. Look out for Charlotte Rampling, who mercilessly steals her only scene as a jaded seductress with no such delusions of redemption.

The performances are terrific all-round, with The Paul ‘Pee Wee Herman’ Reubens in a particularly surprising supporting turn, exuding plenty of creepy pathos as a tragic figure from Henderson’s past. The sisters are excellently portrayed: The West Wing’s Janney as a die-hard optimist trying to support her irreconcilably damaged family, Sheedy as an embittered ice queen, and Henderson the pick of the three as she radiates anxiety and self-doubt. But they are all topped by the work of young Dylan Riley Snider, who does a magnificent job as Janney and Hinds’ confused son, in the unenviable position of struggling simultaneously with his approaching adulthood and the aforementioned unpalatable truth about his father.

If you were expecting Solondz to have eased off the heavy a little after all these years, or provide his doomed characters with a happier denouement than the ironically-titled first film gave them, you will be disappointed. The director’s vision is still mercilessly bleak, all helped along this time with an unsubtle pinch of post-9/11 paranoia.

It would be an unbearable watch were there not so many genuinely funny moments, usually delivered via the zippy dialogue. It’s not always – though it mostly is – laughter in the dark either, there’s an occasional but very noticeable recurring element of quirkiness about the film that recalls the gentler, Wes Andersen-style approach to indie comedy. And there’s a feeling that Solondz really does love loves these complex, deeply-flawed characters, in spite of the nihilistic plot he subjects them to.

If you’ve a very high misery threshold and like your comedy none more black, then this is the perfect film for you.