Introducing… Willis

Hayley Willis – Willis to you and me – is a black blues/soul singer of indeterminate age from the southern United States, trapped in the body of a young white woman from west London. Her debut album, Come Get Some, was released by 679/Warners in the noughties to great acclaim for its startling assimilation of US blues and soul – and country and folk – styles, and for Willis’ vocals, which were as mesmerizingly raw and authentically powerful as the pre-war belters whose spirits she so effortlessly summoned. Willis, the critics agreed, was a true one-off.

And then Willis – who studied Television and Film with Drama at University before spending several years immersed in everything from psych and krautrock to funk noir, working at London’s legendary Soul Jazz record store-cum-label – seemed to disappear off the face of the earth.

In the meantime, a whole slew of soul girls with names like Amy and Duffy came along and filled the gap she’d left. Willis could have been a contender, but she was always keen not to telegraph her sex, just as her songs deliberately presented a blurry image of a musician of no fixed sex or sexuality. “There had been a lot of conversations [at the record company] about my picture not being on the cover and being told that wasn’t a good idea,” says Willis. “But I chose not to have one on there because all female artists are sold on being overtly sexual and I didn’t want my music to be gender specific. There were lots of [internet] forums asking whether I was a man or a woman and I had no problem with that. I didn’t want to kill that buzz, and I don’t particularly want Willis music to be about being female.”

Despite her absence from the scene, there were some who refused to forget about her: fans would email and gently suggest that the world needed another Willis record. And so she decided, after much soul-searching, to “pick myself up and dust myself down” and make that long-awaited second album. “It took a while to find my mojo again,” admits Willis. Mojo regained, the direction of her second album was determined by a dream, a dream that would provide not just the title of the record but also the imagery, atmosphere and central theme.

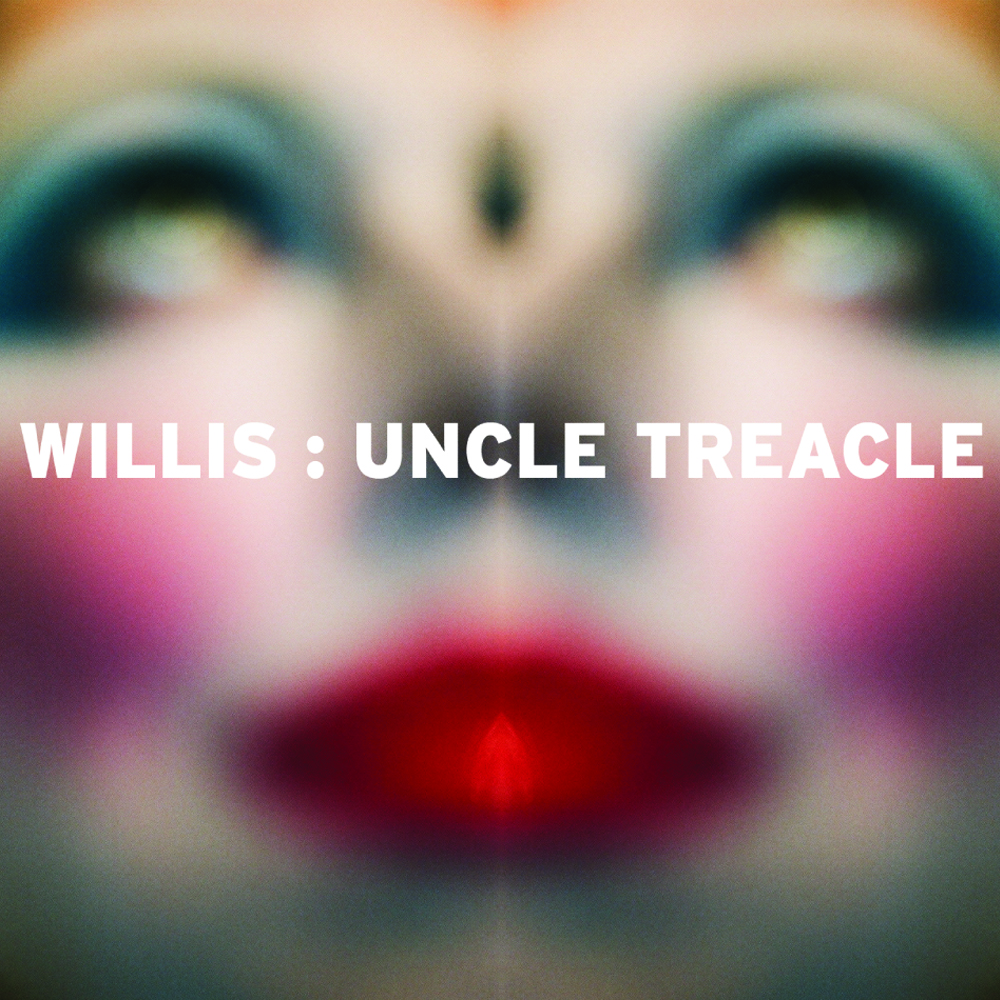

“I dreamed about this character who was a sort of cross between Felix The Cat and Papa Lazarou from the League Of Gentlemen,” she revals. “When I woke up I had the idea for Uncle Treacle.”

Willis is loathe to commit to one single understanding of Uncle Treacle, but agrees that this record of busy, bustling noise, of songs that hit you with an almost feral force, this merry maelstrom of voices and instruments, has about it the air of a surreal, dark carnival.

“It’s not a concept album,” she explains, “but Uncle Treacle is the nucleus of it all and the songs are like waves feeding off that.”

Those songs are as vivid and visceral as your last nightmare. Candyman is like a mad Balkan waltz, and finds Willis moving with ease up and down the vocal range, from throaty to threnody. Get In The Ring has such a hectic energy you imagine dozens of players in the studio grabbing whatever instrument was at hand – Willis likes to encourage participation. Round Again moves at the speed of a tango and is tangy, as in saucy, as in charged with an erotic force.

You sense that much of the music on Uncle Treacle could have existed without the impetus of rock’n’roll – it comes from a pre-rock place; a masked gathering in a mysterious forest at night. Hell-Money-O brings things forward with a withering attack on our acquisitive, consumerist culture, but as ever the music is the most livid purple rhythm’n’bruise. October is less frenzied, with acoustic guitar and a mournful violin figure. Weatherman is a percussive assault. On What You Want For Me, Willis slips into the guise of a back-porch blues woman. Finally, she strips Dolly Parton’s 9 to 5 back to the bare bones of the original, reminding us of the bluegrass country girl who composed it (Parton. It reveals a stark, dramatic protest anthem. “I like doing covers, but I always make sure I turn the original on its head,” says Willis, whose version of Cameo’s Word Up was featured on an episode of CSI: Miami.

She agrees that her songs conjure distant places and times even if she is careful to always reconfigure her influences, whether they’re from the Victorian or pre-war period: “I like to absorb, then regurgitate in a new way.” She always gives a contemporary spin, just as her music features programming and ProTools alongside accordions, ukuleles and zithers.

Uncle Treacle has a sustained mood and detailed richness that would work well as the soundtrack to something strange on-screen. “People tell me my music’s cinematic and I could imagine it being used in a film,” she says. Willis produced the album, and her vocals fill every last space in the same way that a high-energy actor can dominate every scene. The individual contributions of the musicians combine to make the swirling, intoxicating whole – think Tom Waits’ swordfishbones meets PJ Harvey’s Dry for some idea of Uncle Treacle’s density and intensity.

Willis insists that it’s a triumph of collaboration rather than solipsist invention. Her directions for the other players were, she admits, eccentric – she would sit musical partner Pascal Glanville down and “show him three pieces of fabric and 12 photos, then I’d play him three films and say, ‘Do you understand what I mean?’ And he’d know exactly what I meant!” Uncle Treacle shows a headstrong artist successfully realising her idiosyncratic vision with a cast of sympathetic associates.

“Everyone helped interpret what was inside my head,” she says. “I was incredibly fortunate to have found them.” And we are incredibly fortunate to have found Uncle Treacle, even if it is recommended not to be listened to last thing at night.

Willis’ ‘Uncle Treacle’ will be released by Cripple Creek Records on 27th September 2010