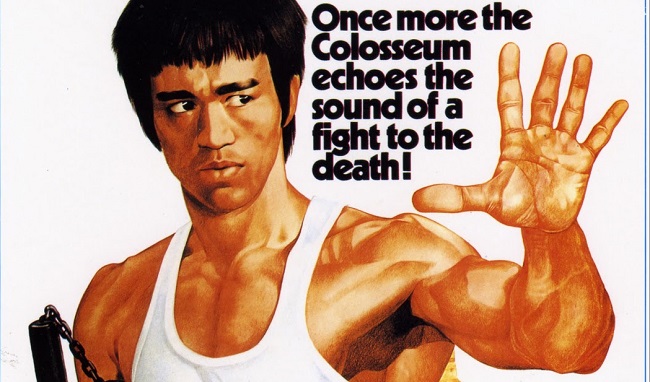

Action Heroes – Bruce Lee: Way Of The Dragon

When the subject of doing these retrospectives came up at Filmwerk Towers, I immediately began mentally sketching out each film. It quickly became apparent that even though I had my favourites among my favourites; I was going to find the actual writing of them a challenging, and even weirdly illuminating experience. I would hesitate to use the old ‘voyage of discovery’ chestnut, because I still have some self respect, but you take my inference. Sometimes a movie that you love dearly, and know inside out, and back to front, is the hardest one to find your groove with in terms of writing about it. Happens all the time. So when It came to drafting out this particular retrospective; I was fully expecting the phenomenon to be invoked. That is because today we are talking about film number three in the Bruce Lee canon, and one of my personal favourites. Way of the Dragon (Return of the Dragon for some of our North American friends), marked the completion of Bruce Lee’s transition from Hong Kong superstar under contract, to autonomous filmmaker superstar extraordinaire. On this film he would be writer, director, producer, fight choreographer, and of course star. It would be the first (and only) time, he would truly be in the driving seat, and master of his own destiny on a completed film project.

As is my won’t, some background, and apologies in advance to those who may find the following to be partially retreading points raised in either The Big Boss, or Fist of Fury retrospectives. Naturally, each retrospective has to be able to stand alone, and explain itself without having to ever wholly rely on reference to any of the others in the series, hence some reiteration of key points may be inevitable. Having said that, I will try not to repeat myself exactly.

OK, so back in the 90s, I owned all of the Bruce Lee movies in a VHS box set (excluding Enter the Dragon, which, no doubt due to some licensing/ownership blockade; never seemed to be included in these types of collections). This set did however, feature the truly objectionable Game of Death II (which, thankfully we are not bothering to cover in these retros, save for a quick mention in the Game of Death piece), and also sported a bonus tape featuring two or three of the best old documentaries, which is where I really first began to learn more about Bruce Lee. It was actually the second such set I had owned, and on the whole, was a serviceable enough package. I kept it in regular use until giving up on VHS completely around 2001. Luckily, right around this time; Hong Kong Legends began re-releasing all the movies in nice, clean, expanded, restored, widescreen DVD editions, and so a slow process of replacement began to occur over the next few years. As mentioned in my Fist of Fury retrospective, both of my original VHS box set editions, featured the James Ferman (then head of the BBFC) era, heavily censored cuts of the movies. These BBFC butchered versions enforced the wholesale removal of every single scene featuring Bruce wielding his trademark nunchaku weapon (literally, every frame was exorcised, except the odd shot of him tucking them in to his waistband). Incidentally, for those of you old enough to have experienced this; these were the same weird UK censorship forces that created the infamous and confusingly titled ‘Teenage Mutant [Hero] Turtles‘ – removing the terribly dangerous, child corrupting word ‘Ninja’, as well as all images of young Michelangelo wielding his humble rice beaters in a half-shell), crazy times eh?! Younger eagle eyed readers who don’t remember that, may have felt some of Ferman’s weird influence in this matter anyway, as the Bruce Lee bio/drama Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story was also subject to certain idiotic cuts in the UK. Not to want to allow ourselves to be sidetracked too much, but I feel that poor James Ferman has got a bad rap from me of late, and deservedly so in these cases. However, that being said; I quite liked the fellow, and in terms of the frequency and intensity of their interference; the BBFC certainly improved their reputation under his tenure. Put it this way, Mary Whitehouse had no love for him, which kind of endears him to me straight away.

Anyway, despite the ridiculous persecution of the humble nunchaku (not to mention the resulting horrendous continuity and scene flow issues, horrid pan & scan TV format, and grainy print), I loved Bruce’s movies dearly, and practically wore those tapes down to the sprockets. Of all of the included movies; it was certainly today’s subject movie, that stood out as the strongest contender for favourite at the time, and it vied for supremacy with the more obvious, Enter the Dragon, (owned of course on a separate tape). I will talk about this again in more detail when we get to it, but like most kids my age, Enter the Dragon was the first, most accessible, and most indelible Bruce Lee movie you saw growing up, and it’s Hollywood production values gave it a natural advantage in that sense; making objective comparison trickier but not impossible.

For me, Way of the Dragon was usually the instant ‘go to’ Bruce Lee movie to watch as a sort of ‘tonic’, after sitting through the unfathomable strangeness of Game of Death. I did this so often in fact, that when watching ‘Way’ even now, I’m always genuinely delighted, and almost surprised at how much actual, real, honest to goodness Bruce Lee there is in it. If that sounds crazy to you, then all will be explained in the Game of Death retrospective (as well as an attempt to explain why I even watched it that much to begin with). For now, let me admit that the notion of being delighted that your leading man is actually in the movie, does sound odd indeed. But go watch Game of Death, check out the scene where they use a life-size cardboard cutout of Bruce’s face stuck to a mirror, and then we’ll talk.

Moving on swiftly.

As usual, for those that maybe haven’t seen all of Bruce Lee’s movies, or are maybe unfamiliar with the specifics of each of them individually (suffering the blend and bleed phenomenon described in The Big Boss retrospective, where key scenes, images or concepts blend the movies together in an indistinct way; here’s a quick recap of what to expect from Way of the Dragon.

It’s a pretty simple premise really. Bruce plays Tang, a young man who travels from Hong Kong to Rome, sent to help protect his friend’s young niece’s restaurant. It turns out that the local mafia boss wants to ‘acquire’ said establishment, and Chen (the nice, and pleasingly progressive, defiant niece in question), and her uncle Wang, simply won’t sign it over to him.

Cue escalating intimidation techniques, threats, disruption of patronage, and plenty of reasonably good natured fighting….at first. The character of Tang is what we could call the first perfected Bruce Lee archetype. He is tough, honourable, proud, unflappable, strong of mind and body, and as honest as the day is long. He cannot be bought or intimidated, and is quick to show any bad guy the back of his hand, or the sole of his Kung Fu slippers. He is also supremely skilled, and more than a match for any number of tuppenny mob thugs ranged against him. He attempts to teach Chen’s loyal restaurant bus boys his ‘Chinese Boxing’ techniques (they all favour karate at first), and after a shaky start, ingratiates himself with them and quickly becomes their leader, at least in terms of their resistance to the mob attacks. Chen begins the movie full of doubt regarding Tang, both in terms of his character, and a broader resentment of the need for him to even be there. However, she is also eventually won over by his commitment to the task at hand, his determination, and of course, his impressive physical prowess. In typical Bruce fashion; this obvious ‘love interest’ potential is not explored at all. I find it interesting that he could just have easily made Chen and Tang related, thereby nullifying the romance angle entirely. Instead, he chose to make Tang almost amoeba-like in his disinterest in Chen that way, and despite some scenes clearly showing that she may well be developing amorous feelings; their relationship remains very platonic. Some folks I’ve talked to, and even various online sources incorrectly believe the characters in fact are related (cousins usually). If you listen closely to the dialogue, it’s clear they are not. If any more proof of Bruce’s attitude towards the ladies is required, watch the scene just after Tang meets Chen at the airport. Tang is invited up to a very lovely lady’s apartment (it’s not clear if she’s a prostitute or just really horny for some Tang action), but when unexpectedly presented with her rather lovely breasts; Tang freaks out and gets the hell out of Dodge at top speed.

Anyway, I digress.

Going back to the subject of Tang winning Chen and the bus boys over; it is precisely these most admirable of qualities in Tang that, instead of actually diffusing the situation; of course causes it to ramp up in severity to vicious, and eventually deadly proportions.

Ultimately, Tang, Chen, and the bus boys must defeat the increasingly menacing and serious forces ranged against them. On top of this, they suffer an unexpected, cruel and poisonous betrayal within their own camp, when it is revealed that Chen’s uncle Wang is a traitor. In a rather ‘off tone’ moment, Wang brutally kills several of their number in the final reel, before getting his comeuppance.

The movie climaxes with the mob boss bringing in their most lethal killer for hire, in order to kill Tang and take the restaurant forcibly.

Of course, they fail.

I think that roughly covers the gist.

Segueing from Fist of Fury to Way of the Dragon; It seems obvious that Bruce Lee was on a mission to make a very different film to that which had come before. He had been unhappy with some of the artistic and dramatic choices he’d been obliged to accept in his two previous movies, and was not about to make a third one that way. If there were long standing, accepted limits and confines to the Hong Kong film industry (the industry that Lee had, in just two movies, become the undisputed king of), then he was equally as rapidly wriggling out of each and every one. He was out of contract with Golden Harvest, and a huge star; which meant he would be coming to the table with some pretty irresistible bargaining chips.

As a result of this new found autonomy, sweeping changes were instigated; not the least of which was the formation of a new production company with Raymond Chow (Concord Productions Inc), through which his films would be produced from now on. Way of the Dragon was of course the first fruit of the new flesh, and represents Bruce cut loose, free to navigate, and master of all he surveys. Critics of the film might point to this as perhaps being a bad thing i.e. with no-one around to tell you ‘no’, you run the risk of making ‘Magical Mystery Tour’ instead of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ if you get the analogy. The flip side of that argument of course is to quote the saying ‘A camel is a horse designed by committee’, and remember that sometimes great art can only be the work of a single auteur.

As mentioned at the top of this retrospective; Way of the Dragon was Bruce Lee’s first foray into directing, as well as writing, and producing. I’m not so sycophantic as to sit here and tell you that Lee’s directorial prowess matched his martial arts skill; there are certainly some nice setups, and one or two adventurous angles now and then, but it’s not particularly spectacular in this respect. As a director, Lee was on a steep curve, and to be fair to him; he does a very serviceable job in delivering an enjoyable, entertaining and thrilling movie. He brought a certain degree of Hollywood cinematography to the look of certain key pieces (and a noticeable reduction in the more typical Hong Kong cinema crazy cuts and zooms). Lee uses the attractive and exotic locations of Rome to maximum effect (I’ll bring this up again in a moment), and at least for a while, Bruce plays up the rural Chinese ‘fish out of water’ factor to both comedic, and dramatic reward. However, as most of the significant supporting characters are Chinese folks living in Rome, this aspect is more limited than it obviously would be, had Tang been the only Chinese character amid a supporting cast of Italians for example. Ah yes, I mentioned the comedy, and herein lies the rub that bothers many people about this film. The comedic sensibility (particularly during Tang’s initial arrival at Rome International airport), is something of a shock to the system for anyone coming off of the dramatic intensity of Fist of Fury. Personally, I have always liked this little light hearted and generous introduction to Lee’s latest character. For me; it allows Tang to be immediately crafted as a very different dude from Lee’s previous heroes. I also think it helps to reinforce him as a noble, likeable guy once the whuppassery commences later on. The light hearted touch is maintained throughout, and Lee is genuinely amusing to watch, when he’s not being incredible instead. This tone takes a knock when the aforementioned betrayal of Wang happens; which is why that plot development comes as such a shock (and not an altogether welcome one for some).

As well as the locations (and no doubt, partly because of them), Lee hired several notable western martial artists to add a more international appeal to the movie. Firstly, there was Bob Wall, who would also play a prominent role in Enter the Dragon, but most significant was of course a certain hairy backed, slightly ginger Karate champion. Yes, Mr. Carlos Ray ‘Chuck’ Norris appears playing the aforementioned climactic showdown über nemesis, Colt. Norris’s scene with Bruce has become the stuff of cinematic legend, and for most it’s easy to see why. It is truly a mini masterpiece of perfectly focused fight choreography. It must be said that when it really mattered; Lee was exceptionally canny at casting the right people to be his fight opponents. I will talk more about this in the Game of Death retrospective, because it is so much a fundamental part of that film’s inception. However, the seeds of it are already present in the casting of both Norris and Wall in villainous roles here, as well as a brief, and unflattering appearance (not to mention an instant dismissal from Tang), of sixth level Hapkido master Hwang In Shik. These three men were properly formidable and well respected opponents for Bruce (and legitimate fight champions in real life – which is very key). Yet, when ranged against Lee’s electric presence and most importantly; the first real on-screen interpretation of his martial arts philosophy of ‘no way, as way’; both American men in particular look slow, heavy footed, and awkward. In juxtaposition to Lee’s lithe, elastic, almost weightless fluidity; all three seem trapped by the very styles they are bonafide masters of. As we shall explore in much greater detail in Game of Death; this was absolutely built in by design. A little more on this in a moment.

In my opinion, the fight choreography, and Lee’s shot design and camera coverage of it, is peerless to this day. The action is wonderfully grounded in reality, albeit the absurdly impressive reality of Bruce’s electrifying martial arts skill, and the story mostly skips along at a nice even pace. As a director, Lee’s coverage of many of the sights of Rome can seem a little gratuitous in places. More than once or twice, one finds oneself jumping out of the movie and remembering that Bruce really had to try and shoehorn as much of the city’s sights into his movie as possible. This being part of the deal of low budget location filmmaking; using what the location gives you for free, to maximum effect, and running the risk of over milking it. Lee certainly lingers and drifts over more than a few statues, fountains and squares throughout the movie, and it is here that the otherwise pleasing pacing takes a knock. On balance, I guess we can give him a pass on the slightly copious footage.

However, he’s all business at the right times though. Some of the best shots are to be found in and around the Colosseum during the lead up to his now legendary fight with Norris. All that stuff was shot guerrilla style too, with not a permit in sight. The fight itself was almost entirely shot on a sound stage, using a mocked up set, and theatre style painted backdrops. Watching the movie again these days, particularly the nice cleaned up, crisp HK Legends DVD special editions; that little Colosseum set convinces no one, but I don’t recall it ever being a problem back in the day, and nor is it now. Somehow, suspension of disbelief is maintained if you’re in the moment. Continuity with the location shots before and after the fight, is also pretty good, which helps a great deal of course. I never noticed the subterfuge back in the day, I must say.

One of the reasons I think any budgetary shortcomings shouldn’t really phase the modern viewer too much, especially once the fists and nunchaku start flying around, is that It’s all one can do to try and prise one’s eyes off of Bruce’s constantly fluid, magnetic physicality. We even get an entire section of the Lee/Norris fight shot in slow motion. Before you think to yourself “Huh, big deal, so what?!”, try and remember the last time you saw any modern, unarmed close quarter fight in a Hollywood movie, framed in medium and long shot, and delivered in extended slow motion. Doesn’t happen. Modern movie parlance tends to favour close up shots, jump cut editing, and every other trick in the book to try and add dynamism and kinetics that aren’t actually present, and paper over less than convincing technique and average choreography. Some of the fights in The Bourne Identity come to mind immediately, as an example of how this type of editing can really create a lot out of very little, if done well. Framing your fighters in a full body two shot, and opting for slow motion is pretty much the polar opposite of that, and takes no prisoners; forgiving absolutely nothing. Bruce knew this, and deliberately did it anyway. He knew that his measured, balletic, constantly fluid motion, lightness of step, and perfectly lean physical form, would be offered up for lingering scrutiny by the viewer, and look fantastic. He also knew that Norris’ naturally heavier set physicality (dialled in on purpose for the movie), and his motive style, would suffer, and appear horribly limited, rudimentary and clumsy under these same conditions. Bruce was of course, spot on. Although, I would go so far as to say that, in shooting that part of the fight the way he did, he very nearly ran the risk of damaging Norris’ credibility in the eyes of the audience (for some modern viewers, the damage is done). After all, Colt is defined by the narrative as being the most ultimate of badass opponents, so it was a very fine line Lee was treading.

In a more abstracted historical sense, It is also important to note, that the fight itself, is a clear dramatic demonstration of Bruce’s emergent martial arts philosophy of ‘no way, as way’.

At one stage, Tang’s fixed style ‘Chinese Boxing’ approach is comprehensively losing the fight for him, seemingly unable to penetrate Colt’s iron defences. Seemingly, the basic potentials of the two men are just too weighed in Colt’s favour. Tang abandons set form, and begins bouncing around oh his toes like Ali. He uses his natural speed and flexibility to exploit all of his previous disadvantages; flipping them around into natural advantages over the bigger, slower man. Suddenly, Colt finds himself in a world of trouble, completely outmatched by Tang’s ability to adapt and flow around him like water. The tables turn, and Tang becomes practically untouchable. It’s not too subtle, but it is some bold magnificent fight cinema, shot clearly and beautifully for all to see, no tricks. What’s more, the subtext is clear: Adaptation, flexibility, and no adherence to any set forms, is the superior combat approach. Set forms impose limitations, and a warrior must be limitless in his ability to adapt and respond to the situation presented to them.

Bruce would plan to cinematically hammer this philosophy home even more clearly in the unfinished movie [The] Game of Death, and if this last sentence confuses you, all will be explained in the retro for the finished movie Game of Death, coming soon.

So, Way of the Dragon further cements Bruce as a through and through noble hero. Yes, there are one or two fatalities by his hands (or slippered feet), but they are always VERY bad guys, or legitimate life or death situations. Gone is the rather gratuitous death dealing to all and sundry, both lowly and critical; that either Cheng or Chen (Bruce’s characters in The Big Boss and Fist of Fury respectively), would deal out.

Even when Colt (by his own stubborn inability to concede defeat, remember), buys his one way ticket to hairy heaven, Bruce is appalled at what the other man has forced him to do. Despite this, he honours his fallen opponent by collecting up his dusty karate Gi jacket and belt, and places them carefully over his lifeless body in a poignant moment. It is a proper tribute to a hard fought victory against a more than worthy adversary.

As is often the way in Hong Kong action films, the hero does win out in the end, but at what cost? Through his own defiance, and of course, uncle Wang’s treachery, many are now dead, even if Tang’s hands are personally less bloody. Even though the villains have been vanquished, and the restaurant saved; the tone is somewhat muted, and there is no real glory in the kind of victory offered here. Life goes on, and Tang says his goodbyes and returns to Hong Kong. He’s is a hero of course, but again; the question is raised. What would have happened had he simply not come to Rome? Perhaps Chen would have eventually given up, and sold the restaurant to the mobsters (it seems clear that they were at least offering a reasonable sale price at first). She may of course have even lost the restaurant with no compensation at all. Crucially, there seems to be a sense that the film does set up a niggling thought that, had Tang just stayed in Hong Kong; no-one would have died at all. This is an interesting line of thought, and one I like to think was considered and acknowledged while Bruce was writing the movie.

It’s not a downer ending per se, and the film does not feel like it falls flat at the last hurdle or anything. True, it doesn’t end with anything approaching the kind of light slapstick comedy it began with, and that lends a certain imbalance to things. However, for me, Bruce’s screen appeal and charisma carries it to the last frame.

Way of the Dragon represents something of an interesting check point in Bruce Lee’s filmography. It was the last project he completed on his own personal career trajectory, before that trajectory was sent off on a tangent with the sudden green lighting of Enter the Dragon (a very different animal, as we shall see).

Naturally, I will talk a great deal more about this in the retrospectives of both Enter the Dragon and Game of Death. But it’s clear that, at least in terms of its philosophical and emotional thrust, and of course, Bruce’s continuing desire to promote on-screen, his approach to martial arts; Way of the Dragon is really ground zero, and pointed the way towards the aforementioned unfinished project The Game of Death. As we shall see, despite his best efforts otherwise; it doesn’t really relate to how Enter the Dragon turned out at all.

Having said that, of course it is Enter the Dragon that actually got produced and released the following year, and is next on the list for discussion by yours truly.

So let us gird our loins and move on to that seminal film now. As we all know, It would be Bruce’s last completed project before his tragic ‘Death by misadventure’ just 6 days before it’s release.

Author’s note: So my concerns that I would not find my groove, and struggle to write this retrospective proved unfounded, and I’ve managed to prattle on about this lovely movie in quite the epic fashion. Apologies for that, should apologies be necessary. Perhaps the remaining retrospectives will prove a little less vast.

Here’s hoping!

Ben Pegley