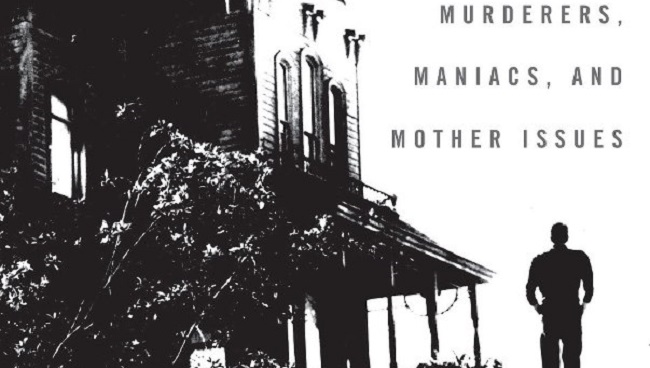

Hitchcock’s Villains: Murderers, Maniacs And Mother Issues Review

Authors: Eric San Juan and Jim McDevitt.

Some of the most colourful villains in cinema’s rich history have been those in Hitchcock films. Think Robert Walker as the rather campy and thinly veiled homosexual Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker) in Strangers on a Train (1951) or Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) in Psycho (1960). It is perhaps a little hard to imagine today what a different kind of ‘villain’ that Norman Bates was – there had been no one like him before. He did not fit into the archetype of snarling monster villain or ruthless killer; he was far more complex drawing on deep rooted psychoanalysis to draw him out. At the heart of this was the mother issue – that it was not Norman but the part of his brain that was controlled by his ‘mother’ that was killing.

Some of the most colourful villains in cinema’s rich history have been those in Hitchcock films. Think Robert Walker as the rather campy and thinly veiled homosexual Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker) in Strangers on a Train (1951) or Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) in Psycho (1960). It is perhaps a little hard to imagine today what a different kind of ‘villain’ that Norman Bates was – there had been no one like him before. He did not fit into the archetype of snarling monster villain or ruthless killer; he was far more complex drawing on deep rooted psychoanalysis to draw him out. At the heart of this was the mother issue – that it was not Norman but the part of his brain that was controlled by his ‘mother’ that was killing.

Grouping the nine films singled out for detailed discussion there is a clear thread and pattern that runs through nearly all of them. The films studied span throughout his career: the terrorist family man Karl Anton Verloc in Sabotage (1936), Uncle Charlie, the alleged Merry Widow murderer who hides out with his middle American family in Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Alexander Sebastian the renegade Nazi living in Brazil in Notorious (1946), the two student killers who murder for the experience and kicks in Rope (1948), the aforementioned twisted Bruno Anthony in Strangers on a Train, the wealthy fifth columnist Phillip Vandamm in North by Northwest (1959), Norman Bates in Psycho (1960), the violent rapist tie strangler Bob Rusk in Frenzy (1972), Hitch’s last masterpiece and most controversial of all is Scottie Ferguson in Vertigo (1958), who one can argue that he was a villain at all, but the authors seem to be under no doubt. Looking at all these films together the links become clearer with on many occasions the mother being at the heart of it all – whether she be domineering or molly coddles her offspring. With Psycho it’s clear: overbearing mother brings Norman up sheltered from women, tells him that they are evil and their flesh is sinful. Years before she is killed in a fit of rage by Norman who then preserves her as though she were still the dominating force in his life. The mother in Notorious works in the same way and is perhaps the most snarling villain in the entire film. For Bruno Anthony’s mother she is the opposite pampers to every one of her capricious son’s demands much to the chagrin of Bruno’s father (who Bruno wants to have killed off).

Throughout the book the author’s try to link up what we know of Hitchcock’s personality and the villains themselves. This can be dangerous territory. At one point the authors are labelling Hitchcock biographer of some sometimes gossipy tabloid readings of Hitchcock and yet on the other hand they are trying to compare Hitchcock’s mother issues in his films with the close, not untypical of the time strange relationship he had with his own mother. Psycho-biography is always an interesting read but can be presumptuous rather than fact based. It’s duly noted that despite the Master’s own admission of impotence the authors are reluctant to make the distinction with the sexual kicks Bob Rusk gets from killing in Frenzy. They certainly make the comparisons with Claude Rains’ Alex in Notorious and Scottie in Vertigo with his obsession for one woman. It was well publicized that Hitchcock had an infatuation bordering on obsession with many of his (blonde) leading ladies including Grace Kelly and Vera Miles before most famously reaching a disastrous head with Tippi Hedren star of The Birds (1963) and Marnie (1964) – two other films it is noted have very strong mother issues.

Chris Hick