The War Lord Review

Hollywood Medieval history films had tended to be more like westerns with swords and armour showing little interest in any historical detail or even attempt at some kind of historical accuracy. This was the case in both Hollywood and Britain where this medieval past was romanticized à la Walter Scott or the glamorous folk legend of Robin Hood. However, a film released in 1965 altered that course, in Hollywood at any rate. In non-English speaking European countries such as Sweden, Russia and France the medieval period was perfectly realized in a handful of classic films. Sadly this film, despite its good intentions had little impact on what lay ahead while the successful but flawed musical Camelot released a couple of years through that ambition backwards. The film in question was The War Lord and was a joint effort in its creation between director Franklin Schaffner and actor Charlton Heston (before the pair went on to make Planet of the Apes together a couple of years later). The origin of the story of The War Lord began as a play by Leslie Stephens called ‘The Lovers’ which had been put on Broadway 10 years previously. It was not a success but certainly drew the attentions of Schaffner and Heston. The play was adapted and the unsuccessful flashback narrative was negated in place of a straight sequential story. They were both keen on creating an earthy realism hitherto unseen in similar Hollywood ‘historical epics’. Naturally the creative pair was to face many difficulties in realizing these ambitions, wishing to retain an earthy grittiness. Heston also insisted that he have a fashionable dome haircut (the publicity agents and managers tried to prevent this as it would jeopardise his sex symbol appeal), they wanted to film to be shot in England (rejected) as well as a British ensemble cast (again mostly rejected).

Hollywood Medieval history films had tended to be more like westerns with swords and armour showing little interest in any historical detail or even attempt at some kind of historical accuracy. This was the case in both Hollywood and Britain where this medieval past was romanticized à la Walter Scott or the glamorous folk legend of Robin Hood. However, a film released in 1965 altered that course, in Hollywood at any rate. In non-English speaking European countries such as Sweden, Russia and France the medieval period was perfectly realized in a handful of classic films. Sadly this film, despite its good intentions had little impact on what lay ahead while the successful but flawed musical Camelot released a couple of years through that ambition backwards. The film in question was The War Lord and was a joint effort in its creation between director Franklin Schaffner and actor Charlton Heston (before the pair went on to make Planet of the Apes together a couple of years later). The origin of the story of The War Lord began as a play by Leslie Stephens called ‘The Lovers’ which had been put on Broadway 10 years previously. It was not a success but certainly drew the attentions of Schaffner and Heston. The play was adapted and the unsuccessful flashback narrative was negated in place of a straight sequential story. They were both keen on creating an earthy realism hitherto unseen in similar Hollywood ‘historical epics’. Naturally the creative pair was to face many difficulties in realizing these ambitions, wishing to retain an earthy grittiness. Heston also insisted that he have a fashionable dome haircut (the publicity agents and managers tried to prevent this as it would jeopardise his sex symbol appeal), they wanted to film to be shot in England (rejected) as well as a British ensemble cast (again mostly rejected).

However, much of the earthiness and reality of the story remains intact. It is set in the 11th Century Lowlands and sees a troop of Norman warriors sent to take and hold in a castle against the Frisians. In an opening battle to take the castle (more like a fortified tower) in the marshy locale they also kidnap, unbeknownst to them the Frisian nobleman’s young son. When they enter the village under the protection of the tower they also find much in the way of superstition. The Normans are led by Chrysagon de la Cruex (Heston) and his squabbling brother, Draco (Guy Stockwell). On entering the village Chrysagon takes to a beautiful young virginal woman, betrothed to marry a local villager. Another local custom allows a noble ruler to deflower the girl/woman if she is a virgin on her wedding night (this custom is mooted as myth by some historians). Although he attempts to carry this out, it is clear that Chrysagon is unable to go through with this but the girl decides to stay with him anyway and soon they become willing lovers. Understandably this makes the young fiancée very jealous and he assists the Frisians in trying to take the castle, leading to the climactic and actually quite impressive battle sequence in which the Frisian raiding party attempting to storm the castle using fire, arrows, battering rams and portable towers to breech the defenses.

The climax is exciting, a great set piece to the film whereas the opening conflict is less so and falls more into type. This climax attempts to show medieval battle as a determined battle of wills and ingenuity rather than a ‘cowboys and Indians’ sought of duel that had been the case with earlier films. Heston and Schaffner made a bold effort to make an intelligent film with much in the way of earthy realism. It would seem that Universal Pictures let the film down with its refusals to allow the filmmakers any degree of artistic license but they were able to make do with what limitations they had. It was filmed on the backlot of Universal with some pretty obvious back projection work and matte paintings (although these are better), yet they defeat the object and make the film look more Walter Scott like. Don’t be fooled by the film’s title, for with the exception of the book ended battle scenes the rest of the film instead focusses on superstition in the face of the more enlightened Normans and the politics of the Heston’s knight with Bronwynn, the peasant girl. Therefore, if preparing for an action adventure the viewer will be bitterly disappointed.

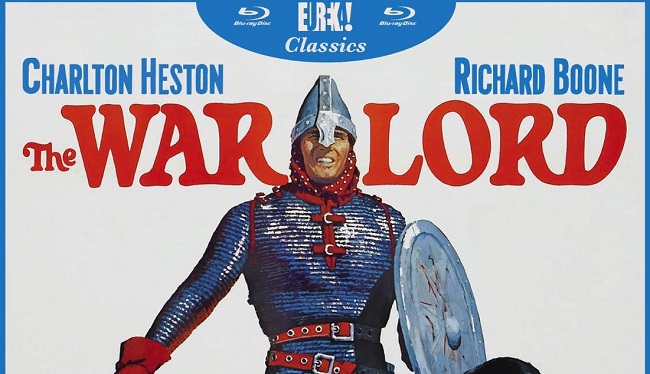

The War Lord is not a classic in the canonical sense but is never the less an interesting film that could have been a great and even fairly ground breaking film were it not for studio interference and as such credit should surely go to Heston and Schaffner in pulling the film off despite their limitations. As it has been released by Eureka, one can expect a good package. With the films poster as the front cover and a Blu-ray 1080p transfer with a 2.35:1 aspect ratio the film looks stunning and beautiful in tone. This sharp image can over emphasize the soft focus and lenses used on the film, but never the less is worthy seeing in this version. It has never been sold in the UK for home entertainment so that alone makes it worthy viewing. There are some good essays and the original review for the ‘Monthly Film Bulletin’ by Tom Milne in the nicely illustrated accompanying booklet.

Chris Hick