Intolerance Blu-ray Review

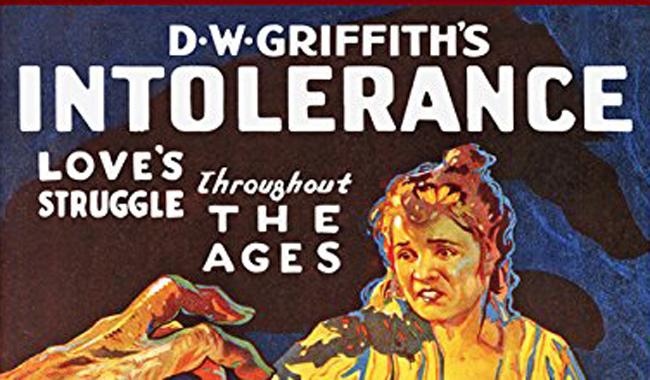

In 1915 D.W. Griffith, one of the great movie pioneers made a feature length film which became a ground breaking movie in narrative cinema. That film was the controversial The Birth of a Nation. The following year he repeated the critical success of that film (although not the box-office success) with a multi-story film called Intolerance. Once again it extended and re-wrote the rules of narrative cinema and storytelling. Intolerance is a four story film that covers four historical eras of social intolerance, cutting back and forth to each story, all of which are punctuated with a universal image of a mother rocking a crib (played by screen legend Lillian Gish). The four stories are: a Judean story of Christ and his struggle with the Pharisees after they attempt to stone a ‘sinner’ and his eventual demise at the hands of Pontius Pilate; a story set in 539 BC Babylonia and a feud between Prince Belshazzar of Babylon and Cyrus the Great of Persia and their ensuing war and the fall of Babylon; another occurs on the eve of the St. Bartholomew’s Day’s Massacre in 1572 in which the Protestant Huguenots face persecution and are massacred by a Catholic majority. The final tale is a modern one about the struggles between capital and labour. A girl, known only as The Dear One is brought up an innocent and vowed to her father that she would never let a man into her room or offer a kiss until marriage. When a young suitor who always seems to be skirting with the wrong side of the law gets upset because she denies him he does end up marrying her and bearing a child by her. During their travails and hardships brought about by the industrialists and their struggle with the Unions, The Dear One and the man become victims of circumstance leading one man to attempt to rape The Dear One. The man is shot by a jealous rival and The Man is blamed for the death and sentenced to death.

In 1915 D.W. Griffith, one of the great movie pioneers made a feature length film which became a ground breaking movie in narrative cinema. That film was the controversial The Birth of a Nation. The following year he repeated the critical success of that film (although not the box-office success) with a multi-story film called Intolerance. Once again it extended and re-wrote the rules of narrative cinema and storytelling. Intolerance is a four story film that covers four historical eras of social intolerance, cutting back and forth to each story, all of which are punctuated with a universal image of a mother rocking a crib (played by screen legend Lillian Gish). The four stories are: a Judean story of Christ and his struggle with the Pharisees after they attempt to stone a ‘sinner’ and his eventual demise at the hands of Pontius Pilate; a story set in 539 BC Babylonia and a feud between Prince Belshazzar of Babylon and Cyrus the Great of Persia and their ensuing war and the fall of Babylon; another occurs on the eve of the St. Bartholomew’s Day’s Massacre in 1572 in which the Protestant Huguenots face persecution and are massacred by a Catholic majority. The final tale is a modern one about the struggles between capital and labour. A girl, known only as The Dear One is brought up an innocent and vowed to her father that she would never let a man into her room or offer a kiss until marriage. When a young suitor who always seems to be skirting with the wrong side of the law gets upset because she denies him he does end up marrying her and bearing a child by her. During their travails and hardships brought about by the industrialists and their struggle with the Unions, The Dear One and the man become victims of circumstance leading one man to attempt to rape The Dear One. The man is shot by a jealous rival and The Man is blamed for the death and sentenced to death.

Griffith’s innovative use of editing is the driving force behind the narrative but the film also includes some very impressive and innovative camera work too. The iris shutter close up is a trait of pioneering and silent cinema but used to much greater dramatic effect by Griffith. Other images are haunting such as the close-up right into the face of The Dear One when she realises her fate and the situation she is in after her husband’s conviction giving strong psychological impact to the narrative becoming one of the iconic images of silent cinema. In addition the spectacular battle in the Babylonian story is extraordinary and grand in scale. It is also very violent and bloody as we see heads lopped off, spears thrust into men and the equipment that the Babylonians and Persians use against each other such as the climbing towers as hot oil is poured down and the fire spewing tank like battle machine as well as battering rams and giant mechanic spear launchers. The staging of the battle, the sets and set pieces as well as the violent orchestration of the battle are all quite incredible achievements. It is in the Babylonian section that much of the money has clearly been thrown with a cast of thousands of extras. The giant elephants in the sets have recently been discovered buried in a desert outside of LA while a shopping mall in Los Angeles, Hollywood and Highland also has a recreation of the Babylon set as a part of the design giving some indication as how this film has become revered and is recognized in modern day Hollywood/Los Angeles as a film that helped build the city (ironic considering the city and California generally seems to have little respect for its own heritage).

Intolerance cost an estimated $2.5 million, $1 million of which was personally financed by Griffith himself. This was an astronomical sum by the standards of the day and one which nearly financially ruined Griffith but it is easy to see where the money went. But overtime the film has earned its place as a Hollywood great as one of the standout classics of the golden age of silent Hollywood; indeed it could even deserve to be called an Art picture, with a capital A attached to it at that. The film had originally begun life as a feature only with the modern section, originally titled The Mother and the Law before Griffith expanded it with a broader idea centred on intolerance. The rather Dickensian melodrama, The Mother and Law does stand up to being a stand-alone film and is included on the Eureka! Masters of Cinema release with additional scenes added but the raid on a brothel expunged from the film following outrage from the moral right. The other feature length film included on the disc is The Fall of Babylon, yet another feature expanded from the segment in the film. Both these films were released in 1919 and are included on the disc. Also included is an observational documentary, as well as one on the restoration of the film by Kevin Brownlow and the usual high quality booklet to accompany the package.

Despite his clear genius, Griffith is viewed as something of a divisive director following the criticism and calls that The Birth of a Nation was racist. There is definitely more of a humanist story being played out here, what many commentators have dubbed his apology for the previous film, but this seems to be something of a rather simplistic approach to the film and the filmmaker. The picture quality is outstanding whereas in previous releases, many prints of which were available as public domain titles are barely watchable. This makes the film even more impressive than previously realised with relatively few signs of deterioration visible. What the viewer cannot deny is the daring risk taking Griffith was carrying out, a maverick pioneer capable of folly as well as vision, well deserving of that moniker: Master of Cinema.

Chris Hick