Disc Reviews

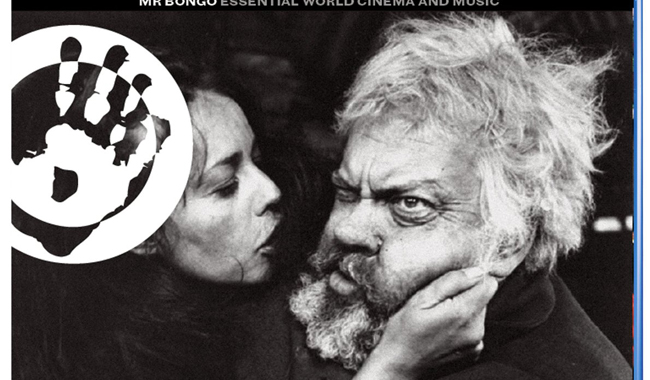

Falstaff: Chimes At Midnight Review

By the 1950s Orson Welles was feeling as if he was gaining more artistic freedom. After the success of Citizen Kane in 1941 this wunderkind director was perceived by Hollywood as a maverick with risky and ambitious ideas, despite said film’s critical acclaim and were therefore wary to finance his film projects. As the studio system became less important so Welles was gaining some freedoms which essentially began with the eccentric indie film Mr. Arkadin in 1955 (also known as Confidential Report). As the 1960s entered Welles found he perfect foil in the guise of the great 1960s arthouse director’s: Pasolini, Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel and Ingmar Bergman. The plays of Shakespeare would not perhaps make great populist entertainment but Laurence Olivier had proven the critics wrong with his three loyal Shakespeare adaptations and so Orson Welles would follow suit with his three adaptations of plays by the Bard. The first two were Macbeth (1948) and Othello (1952) and this third now released on the Mr. Bongo label is Falstaff (also known as Chimes at Midnight) made in 1966. Again Hollywood was not willing to finance the film or have anything to do with it and as a result this would become a Swiss-Spanish co-production, financed in Switzerland and shot in Spain.

By the 1950s Orson Welles was feeling as if he was gaining more artistic freedom. After the success of Citizen Kane in 1941 this wunderkind director was perceived by Hollywood as a maverick with risky and ambitious ideas, despite said film’s critical acclaim and were therefore wary to finance his film projects. As the studio system became less important so Welles was gaining some freedoms which essentially began with the eccentric indie film Mr. Arkadin in 1955 (also known as Confidential Report). As the 1960s entered Welles found he perfect foil in the guise of the great 1960s arthouse director’s: Pasolini, Federico Fellini, Luis Bunuel and Ingmar Bergman. The plays of Shakespeare would not perhaps make great populist entertainment but Laurence Olivier had proven the critics wrong with his three loyal Shakespeare adaptations and so Orson Welles would follow suit with his three adaptations of plays by the Bard. The first two were Macbeth (1948) and Othello (1952) and this third now released on the Mr. Bongo label is Falstaff (also known as Chimes at Midnight) made in 1966. Again Hollywood was not willing to finance the film or have anything to do with it and as a result this would become a Swiss-Spanish co-production, financed in Switzerland and shot in Spain.

In the film Richard II has died and is succeeded to the throne by King Henry IV. Meanwhile, the rotund Sir John Falstaff (played by Welles) spends his days drinking and carousing in the Boar’s Head Tavern surrounded by peasants, thieves, disgraced nobles and wenches. Intercut with scenes of royal machinations and the underhanded behaviour of those in the tavern, Sir John Falstaff with some of these men join the knights and noblemen on the battlefield as the film demonstrates human betrayal at different levels. In the midst of the realties of battle a rather comical figure of the overweight and very round Falstaff dressed in a knight’s uniform is seen trying to dodge the battlefield to comic effect.

Composed of five Shakespeare plays, Falstaff was a recurring figure in many of the Bard’s plays, Welles cleverly producing his own drama from Shakespeare’s writing, clearly understanding much of the human failings prevalent in the premier English writer’s plays. Edmond Richard’s grainy cinematography comes into particular effect during The Battle of Shrewsbury sequence, the long battle sequence that has enough up close gritty hand to hand combat it breaks up the two halves of the film. In addition the shots of the castle with John Gielgud playing the King is stark and majestic as the light beams through a high window.

For many years the film had been critically ignored but has since been rightfully restored as one of Welles’ strong artistic accomplishments but it is unfortunate that the Mr. Bongo release with some changeable picture quality is without extras.

Chris Hick