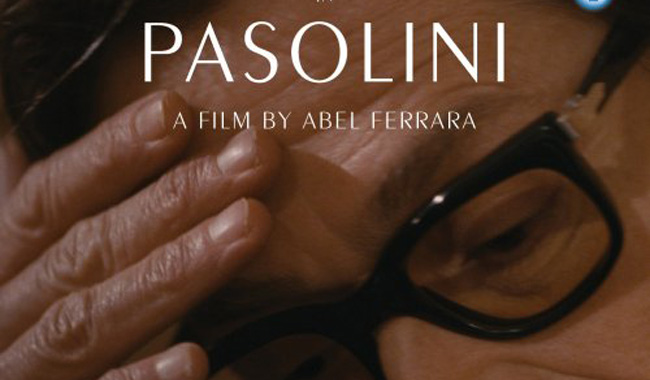

Pasolini Review

The early films of director Abel Ferrara caused controversy on their release: notably the banned video nasty Driller Killer (1979) and his controversial Bad Lieutenant (1992). And so too was it with Pier Paolo Pasolini and most particularly with his last film, Salò: 120 Days of Sodom (1975) about the power of corruption in the dying days of what remained of Mussolini’s fascist Italy. Pasolini was shockingly killed on 2nd November 1975 and Ferrera’s film focuses on the last couple of days of the director and writer’s life and gives an interpretation of what occurred on the night of his murder as history has been a bit sketchy on this, shrouding the director life in further mystery. This has been exacerbated as there were theories that it was connected with Salò following the disappearance of some negatives from the film not long before he was murdered.

The early films of director Abel Ferrara caused controversy on their release: notably the banned video nasty Driller Killer (1979) and his controversial Bad Lieutenant (1992). And so too was it with Pier Paolo Pasolini and most particularly with his last film, Salò: 120 Days of Sodom (1975) about the power of corruption in the dying days of what remained of Mussolini’s fascist Italy. Pasolini was shockingly killed on 2nd November 1975 and Ferrera’s film focuses on the last couple of days of the director and writer’s life and gives an interpretation of what occurred on the night of his murder as history has been a bit sketchy on this, shrouding the director life in further mystery. This has been exacerbated as there were theories that it was connected with Salò following the disappearance of some negatives from the film not long before he was murdered.

The film begins with the director returning from Sweden while working on the post production of Salò. He is struggling to write his next project (Pasolini, as the film tells us considers himself a writer first and foremost but was also a poet) and intended as his next film, Porno-Teo-Kolossal. He is also working through drafting his magnum-opus, a novel he entitled ‘Petrolio’. Over his last couple of days we see him relaxing in the banality of his home, spending time with his mother (touchingly played by Adriana Asti, who acted in several of Pasolini’s films) and friends, as well as an interview, more accurately sparring with an Italian journalist from ‘La Stampa’ as well as spending time with his muse and other regular actor, the puckish Ninetto Davoli.

Pasolini was brought up in Bologna and grew up a communist with strong Catholic convictions – something he had few struggles with as was exemplified in the almost neo-realist The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). He also had a voracious sexual appetite for younger men, often known for picking up rough trade from the poorer parts of Rome (Mama Roma 1962 was a film that spoke of these communities) and around the Termini station. To say that this would be the death of him would be a cruel joke. Within the film there are a couple of shocking scenes – in one he gives a blowjob behind a bush to a young man and of course another being with the young hustler ‘Pino’ Pelosi who was later arrested for his murder.

Casting Willem Dafoe was a real coup to play one of the 20th Century’s great director’s of art films. Dafoe is a spitting image of the Master and plays him with a good deal of subtlety, limiting his use of speaking Italian. Elsewhere it is a fitting tribute that Asti appears, but most significantly is the casting of the now 67-year-old curly haired Davoli, former lover and muse of Pasolini playing Epifanio in the fantasy sequence to Porno-Teo-Kolossal while young Riccardo Scarmarcio plays Davoli.

Extras on the disc include a conversation and Q&A with director Ferrara, cast members Dafoe, co-star Maria de Medeiros and Giada Colagrande with Paulo Branco. Also included is a 23 minute interview with, bizarrely British actor Robin Askwith. Askwith, better known for the 1970s saucy Confession sex comedies talks about his brief experience of working with Pasolini in his adaptation of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) and how he maintained his friendship with the director through letters after the film. This interview would probably be better served on BFI’s release of The Canterbury Tales. Thankfully Pasolini will be better remembered for his films and even his controversy rather than his tragic murder. As Pier-Paolo once said: “To scandalize is a right and to be scandalized is a pleasure”. Needless to say that in Italy Pasolini is still rightly revered as a director of his artistic merit should be.

Chris Hick