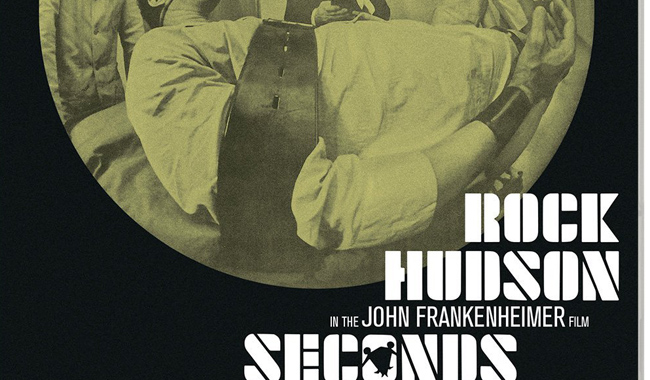

Seconds Review

They say that timing is everything. Well in the case of John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, made in 1966 this is true as he may have been just a couple of years early to tap into the counter-culture zeitgeist and the dissatisfaction of the have it all age. The film is a psychological nightmare seen through the eyes of a banker dissatisfied with his life and forms a part of what is known as Frankenheimer’s paranoid trilogy that was preceded by The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and the apocalyptic Seven Days in May (1964). But this film tapped into its age better than any of his films and ironically is arguably the least known of the three.

They say that timing is everything. Well in the case of John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, made in 1966 this is true as he may have been just a couple of years early to tap into the counter-culture zeitgeist and the dissatisfaction of the have it all age. The film is a psychological nightmare seen through the eyes of a banker dissatisfied with his life and forms a part of what is known as Frankenheimer’s paranoid trilogy that was preceded by The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and the apocalyptic Seven Days in May (1964). But this film tapped into its age better than any of his films and ironically is arguably the least known of the three.

The film opens with a terrifying title sequence designed by the brilliant Saul Bass (who had also designed the posters and title sequences to many of Hitchcock’s films) and played to a frightening organ piece that would have been perfectly suited to any gothic horror. Shot through distorted mirrors we see close ups of a face and head details with other shots of a bandaged head. This alone is enough to give a viewer the frights. The establishing opening scene with its shots of Grand Central Station shows POV shots of the central character of the film as he negotiates the crowds and boards a train. He is then handed a piece of paper by a stranger. The banality of this scene of any rush hour is given a level of paranoia that we are yet unable to fathom. It is truly Kafkaesque in its scale of paranoia. It is slowly revealed that the protagonist is Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph), a banker who dreams of escaping it all. He is no Reggie Perrin. He is a man who seems to be on the edge of a nervous breakdown, discontent with his suburban life, his suburban wife and feels trapped by his privilege and wants to be reconstructed. The piece of paper thrust in his hand is the contact for The Corporation, a faceless, secret group that promise a new life. He enters The Corporation via a slaughter warehouse where he enters a modern space and is asked to wait. They promise him a new life at a cost of $30,000. And so he undergoes surgery, with his past ‘self’ set to be killed in a car accident and he becomes a Malibu artist going under the name of Antiochus Wilson (now he is played by Rock Hudson). As Wilson he is living the bohemian life, surrounded by beautiful young women and joins them in orgies and hippy festivals. But he is still not satisfied and wants to return to his old life and back to his wife. After a waiting period his wish is granted but as the saying goes, be careful for what you wish for and here it is with terrible nightmarish consequences (it would be too much to give away the reveal here).

In many ways this is a film that defies genre categorisation. It has often been labelled as a horror film or a science-fiction film but to attach these monikers to it would be a misnomer and not really accurate. And that is despite the science-fiction elements of a secret organization offering ground breaking surgery or the horror that runs through it. The film is shot by one of the great cinematographers, James Wong Howe. Wong Howe hails from the golden age of Hollywood: he had lit Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express (1932), filmed the gothic horror Mark of the Vampire (1935) with Bela Lugosi and shot the inspired in the ring boxing drama Body and Soul (1945), a film that was a huge influence on Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980). In Seconds he uses close-up wide-angle lenses to create the feeling of claustrophobia and paranoia, not to mention the aforementioned opening sequence. The black and white cinematography also assists in the mood of the film.

To use Hudson in the role of his new self is inspiring. Hudson was famous for his fluffy light comedies with Doris Day or his hero roles in melodramas and women films, making him one of the truly great male pin-ups of his age. Later of course it was revealed that he was gay and would in the 1980s become one of the first top celebrities to succumb to the AIDS virus. But in the mid-1960s he was an icon. Randolph, on the other hand, who plays the banker, is a lesser known actor and looks handsome, but ordinary and jaded compared to the chiselled features of Hudson.

It is a rare treat to see this film and does demand multiple viewings. As usual the clarity of the image on Eureka! is second to none with a host of extras including a thorough booklet and an introduction by horror expert Kim Newman who has done the same for a number of recent horror related release by Eureka!

Chris Hick