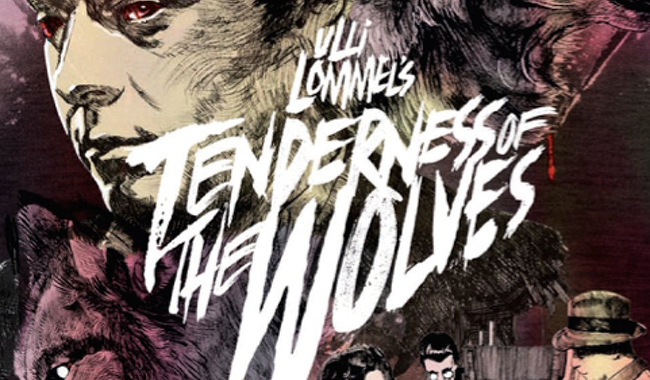

Tenderness Of The Wolves Blu-ray review

There is a shot towards the end of Tenderness of the Wolves (1973) with the bald headed character of Fritz Haarmann, with blood on his lips having taken a bite out of the throat of one of his victims. There was a large black and white still of this scene in a book I owned as a youngster on vampire films. This was always something of a haunting image for me, as haunting as that of Nosferatu’s shadow ascending the stairs. This film was rarely seen in this country and even less so in the USA where it was banned for many years. It fared better in the UK though with a long run at the Notting Hill Coronet on its gay themed evenings. Tenderness of the Wolves is the true story of serial killer Fritz Haarmann, who’s story is every bit as grisly as any horror film, probably more so. The real Fritz Haarmann was known to operate between approximately 1919 until he was caught in 1924 having being responsible for in the region of 30 murders. The film is ambiguously set after the Second World War, probably due to budget constraints and this period costumes available but otherwise the film is faithful to the real life story. Haarmann worked closely with the police investigating black market racketeers, his job giving him justification to prowl the streets of Hanover at night picking up young men, runaways and teen children. He would show kindness and groom them before luring them to his attic flat where he would seduce and murder them by strangulation, afterwards taking bites out of their throats. He would then chop the bodies up and allegedly sell on as meat to neighbours. Fritz Haarmann was executed by beheading for his crimes in 1925.

There is a shot towards the end of Tenderness of the Wolves (1973) with the bald headed character of Fritz Haarmann, with blood on his lips having taken a bite out of the throat of one of his victims. There was a large black and white still of this scene in a book I owned as a youngster on vampire films. This was always something of a haunting image for me, as haunting as that of Nosferatu’s shadow ascending the stairs. This film was rarely seen in this country and even less so in the USA where it was banned for many years. It fared better in the UK though with a long run at the Notting Hill Coronet on its gay themed evenings. Tenderness of the Wolves is the true story of serial killer Fritz Haarmann, who’s story is every bit as grisly as any horror film, probably more so. The real Fritz Haarmann was known to operate between approximately 1919 until he was caught in 1924 having being responsible for in the region of 30 murders. The film is ambiguously set after the Second World War, probably due to budget constraints and this period costumes available but otherwise the film is faithful to the real life story. Haarmann worked closely with the police investigating black market racketeers, his job giving him justification to prowl the streets of Hanover at night picking up young men, runaways and teen children. He would show kindness and groom them before luring them to his attic flat where he would seduce and murder them by strangulation, afterwards taking bites out of their throats. He would then chop the bodies up and allegedly sell on as meat to neighbours. Fritz Haarmann was executed by beheading for his crimes in 1925.

The film opens with the credits over the shadow and footsteps of a figure walking down the wet paved streets. This is one of the first of a couple of reference points to another film which dealt with similar if not the same subject matter – Fritz Lang’s classic M made in 1931. Lang’s film was made only 6 years after Haarmann’s execution but he is not directly stated as the notorious Hanover criminal. The other character and child killer referenced by Peter Lorre’s character in Lang’s film is Peter Kurten, the equally notorious so-called Vampire of Dusseldorf. More of these similarities later. It is some time into the film before we see the nature of Haarmann’s crimes; up to this point they are only alluded to. We see him taking children and young men up to his flat having caressed them. We then see meat being given away. During one police inspection, a newspaper on the floor is kicked and pushed under the room heater stove. This is a reference to a real incident in which the newspaper had covered a severed head tucked behind the stove. We also so get to see that Haarmann is benevolent with neighbours and hangs around with an assortment of salubrious characters himself including his gay lover, the white suited (and looking somewhat like French actor Alain Delon) Hans Grans. Grans often would tease Haarmann and was well aware that his lover would bring up young men and boys to flat, murder them and chop up their bodies. There is one scene in which we see a naked young man with his throat bitten and quite dead lying next to the killer on the bed. There is also a story that Grans had liked a jacket a youth had, who Haarmann killed giving Grans the jacket, making him more than complicit.

The film was made on a very low budget and was initially brought together by the famous New Wave German director Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Fassbinder’s name is attached to the film and almost certainly helped in giving it a broader distribution. He also appears in the film as one of Haarmaan’s seedy associates. Fassbinder had a great deal of control on the film but credit must also go elsewhere, firstly to Kurt Raab the writer and as the main character of the film. His mere presence in the film is very evocative as the serial killer. For the film he shaved his head which again makes another reference to Lorre’s character in M; there is even a scene shot of children playing and a ball rolling which is caught by Haarmann who gently hands it back to the child in another reference to Lang’s film. There are only two scenes in which we see the method of Fritz Haarmann’s murdering. In one he goes from gentleman to clasping his hands round the throat of his semi-naked lover. The semi-naked Raab’s mass moves across the screen as he animalistically throttles the life out of his victim demonstrating some impressive acting skills (although he always claimed that he was an amateur actor). The other credit must go to cinematographer, Jürgen Jürges and his inventive use of lighting under the economy of budget constraints. Jürges used small 150 watt lights called Inkies that helped give some atmospheric directional lighting to faces. This looks particularly impressive in the print on DVD and Blu-ray by Arrow and probably never looked better. Either way the print perfectly captures the cameraman and director’s vision; close-ups on faces are especially effective.

Extras on the Arrow release are not only insightful but give excellent context to a rarely seen film – once again affirming Arrow’s place as the major distributor of cult films demanding either a wider audience or re-evaluation. The extras include interviews with director Lommel (who also provides the commentary), cinematographer Jürgen Jürges and Rainer Will, who played one of the victims. In each the cast and crew give credit to the enormity of Fassbinder’s contribution. Sadly Raab died of AIDS in 1988. There is also a long (20 minute introduction) to the film by Stephen Thrower, author of ‘Nightmare USA’ and ‘Murderous Passions: The Delirious Cinema of Jesús Franco’, although he does make some factual errors by stating that Fritz Haarmaan was the first modern serial killer. This is not even true in Germany as the so-called Silesian Bluebeard was also operating in Germany at the time. He could also made more of the so-called Lustmord in Germany, the nations obsession with sex crime that seemed to permeate German society and culture in the 1920s. Never the less a fascinating and underrated film well packaged.

Chris Hick