The Flight of the Phoenix Blu-ray review

As the 1960s developed the budgets of Hollywood films became massive with each film arriving on the screen seeming to be more like a blockbuster with an all-star cast. Think of The Longest Day (1962), How the West Was Won (both 1962) and Cleopatra (1963) among the many others. This would result in the studio system collapsing and the studios almost becoming bust by the end of the 1960s. One other such film was Robert Aldrich’s The Flight of the Phoenix, a film that is often seen as the proto-Disaster film that paved the way for many of the classics in the 1970s in which survivors have to escape from their catastrophic situation: The Poseidon Adventure (1972), Earthquake and The Towering Inferno (both 1974) among others.

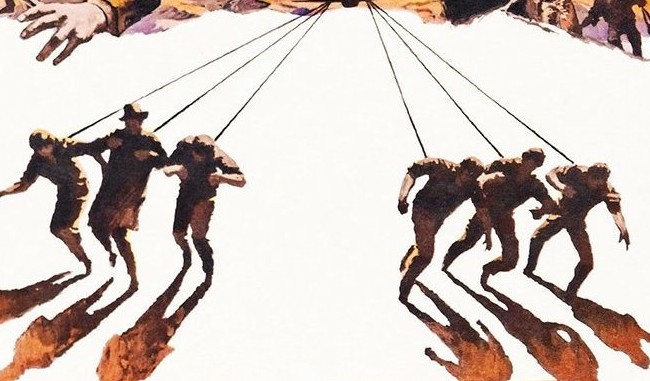

Released by Eureka! in their Masters of Cinema series, The Flight of the Phoenix, a Sunday afternoon favourite is quite a macho film with no love interest (apart from the critically wounded passenger thinking about his wife and a mirage in which Ronald Fraser’s character has a mirage image of a belly dancer – a concession that surely could have been excised from the film). The characters are made up of oil engineers, designers, soldiers, a doctor and other assorted misfits in the Middle East. The passengers are flying in a passenger plane over the desert when it hits a sandstorm and is forced to crash in the desert. A couple of the passengers are killed in the crash and another is critically injured. They are aware that their situation is serious and chances of them being found, especially as they are hundreds of miles off course is minimal. The plane’s pilot (James Stewart) feels terrible guilt for the crash (recording in his log that the cause of the crash was down to pilot error) and his co-pilot (Richard Attenborough) had already lost his nerve previously due to his alcoholism. Among the survivors are a British army officer (Peter Finch), his bitter career sergeant (Fraser), a design engineer (Hardy Krüger), a French doctor (Christian Marquand), some oil workers (Ernest Borgnine, Ian Bannen and George Kennedy), a teacher (Dan Duryea) and an injured Greek man among others. They soon calculate that they have plenty of dates to eat and enough water that will last them less than 2 weeks so long as they don’t exert themselves too much. They shelter from the heat under the wing of the plane and use a parachute to attract attention and as a panoply. Of course over the course of the next couple of hours they try to work out how they are going to get themselves out of the situation from walking to the nearest oasis to trying to flag down a plane flying over at 35,000 feet. The designer comes up with the crazy plan of re-building the plane and using skis to take off from the sand leading to a conflict of egos between Stewart’s pilot and Krüger’s engineer.

The Flight of the Phoenix failed at the box-office costing a great deal of money for 20th Century Fox but it is never the less a pretty good film. Aldrich did not shoot the film in Cinemascope, as most big blockbusters were, but instead in the standard 1.85:1 ratio and therefore filling the screen of most modern TVs. Probably because he felt that this format gave him more control. Therefore for the sake of the sweeping desert vistas that would be found in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) would be replaced by some slick action within the frame which is what Aldrich delivered on. Aldrich proved he was adept at action thinking of other films he made such as Attack! (1956) and The Dirty Dozen (1967), two war films in which he kept the action up throughout. There is still some grain on the image but this film has never looked better than with this transfer. At 142 minutes the film does not seem overly long and moves at a good pace. Most of the actors in the film however were getting towards the latter stages of their careers: Stewart, Attenborough, Duryea and Finch included, whereas the younger actors made up the more international cast: Bannen (Scottish), Marquand (French) and Krüger (German). Fraser offers plenty of down to earth humour in the film but also has a good deal of internal conflict with his commanding officer. Meanwhile, Krüger is also a driven younger character who makes a perfect foil against the wise but grizzled Stewart, while Attenborough pulls through as a character with a good deal of rational sense and open mindedness. By the last half of the film the there are a couple of very identifiable struggles going on – one between Fraser and his rebelliousness against Finch’s commanding officer which he wind by deceit and defiance but most significant is that between the humanistic and world weary Stewart and the pragmatic and rational Krüger character, both driving their determination to win the day. Other than the trailer, the only significant extra is a 25 minute essay on the film by film historian Sheldon Hall who has written books on Zulu and on the genre of the epic.

Chris Hick