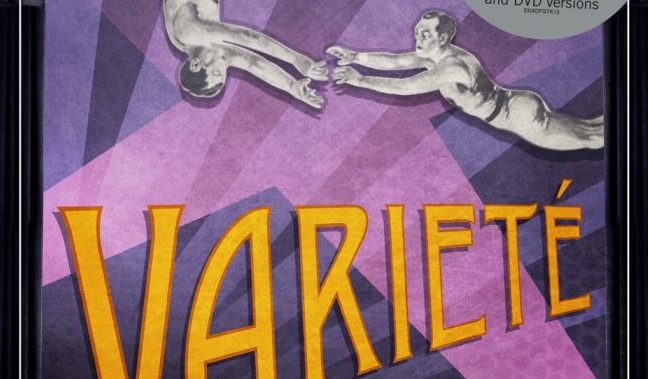

Varieté (1925) Blu-ray release

Ewald Andre Dupont’s German film Varieté (known and shown in the USA on its release as Variety and Jealousy) is most assuredly a zeitgeist film made slap bang in the middle of the Weimar Period in Germany between the First World War and Adolf Hitler’s accession to power. It depicts the famed, perhaps even overstated decadence of that period with a femme-fatale at its heart. Like the femme-fatale in the two films Louise Brooks made for G.W. Pabst at the end of the decade (Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl) the lust of one man after another woman spells his downfall; in art, literature and theatre since the 19th century the evil ways of the sexualised woman had dominated the arts.

The story, based off Friedrich Hollaender’s novel is set around the community of aerial trapeze artistes. ‘Boss’ Huller (played by the great German film star of the silent period, Emil Jannings) is a former trapeze artist who now works in a circus. He is something of a has-been and has largely given up the high wires due to domestic commitments. He is introduced to a young émigré called Berthe-Marie (played by Hungarian actress Lya de Putti) who’s beauty he is immediately attracted to. Fascination and lusting leads to obsession and once again he begins flying through the air with the greatest of ease. Boss leaves his wife and baby and sets up house with Berthe-Marie. He joins up with Artinelli (Warwick Ward) a slightly younger and suave aerial artist and start appearing at the famed Wintergarten in Berlin. Artenelli flirts and begins his seduction of the young attractive woman and ‘forcefully’ seduces her followed by the couple now going behind Boss’s back to conduct their affair.

E.A. Dupont was never able to live up to the artistry of this film. Ably assisted by the greatest of all German silent actors, if not the greatest actor in silent cinema Emil Jannings and cinematographer Karl Freund. This film was not the first time Junnings played a cuckold and would not be his last. One of his great roles was as Professor Rath, the older teacher humiliated in his relationship to Marlene Dietrich’s cabaret singer in the first German sound film, The Blue Angel (1930, also released by Eureka!). Here, the performance and his dialogue is in his facial expressions as we see the cloak slowly lift from his eyes with regards his younger lover. The other great addition to this film is that greatest of all silent German Expressionist cinematographers, Karl Freund. In Freund we see some particularly impressive camerawork with the aerial sequences including some impressive POV shots of somersaults through the air and the views of the crowd below shown as a mass. In one shot we see a very Modernist shot of a kaleidoscopic mass of eyes which when we see as individuals who appear as grotesques waiting for some death defying spectacle. During these aerial sequences the roof of the music hall they perform in looks as though it is electric with sparking stars while the crowd below and the whole scene has an almost Impressionistic quality like a Manet painting.

Hungarian actress Lya de Putti also offers a freshness and sexual allure to the film, of the type would only by superceded by Louise Brooks. De Putti has a rather wide eyed elfin look with the seeming sexual abandon of the flapper generation, an ingenue of the Clara Bow type in Hollywood. She often played vamps and sirens and is perfectly cast as she may appear cute and innocent but is in fact subtlety sexually manipulative. One scene particularly plays this out well as we catch Boss leering at Berthe-Marie’s sheer stockinged legs when he looks back at his wife darning some thick wool leggings, Berthe aware of her voyeur. Not long after this film De Putti went over to Hollywood but never really equalled the success of this role before she died in 1931 at the age of 34.

As ever with Eureka! releases the image of the film is crystal sharp in its 2K restoration. The original German version of the film is the main version on the disc running at approximately 95 minutes, as well as the American version that runs in at 112 minutes. What is missing on this release is any context or visual essay that the film demands. This would give some context in the differences between the German and American releases and in relation to other films of the period. The film, however, is shown with three different soundtracks. There is a piano score on one track by Stephen Horne, a good music arrangement by Johannes Contag (arguably the best soundtrack), as well as the more recent controversial score and songs provided by cabaret band The Tiger Lillies, a group I often saw playing at my North London local. The Tiger Lillies music was specially written for the film and performed at the 2015 Berlinale. For those who love the artistry of 1920s German Expressionist cinema, no collection would be complete without this film. Although it does not quite reach the true artistry of Sunrise (1927), it is more than a fair contender.

Chris Hick