City of the Dead (1960) Blu-ray Review

The City of the Dead opens in Massachusetts on 3rd March 1692. A witch called Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) is being burnt at the stake by Protestants; she is seen hissing and cursing at her persecutors. This scene is surprisingly violent for its period in that it uses lots of close-up shots and in particular showing a lit torch being thrust towards the camera as though the film were in 3D, involving the audience with the action. The film then cuts to the present day and a quite intense Christopher Lee as Professor Driscoll lecturing his young students on the Whitewood witch trials. Naturally this story is referencing the Salem Witch Trials (which also took place in Massacusetts in the same year that this fictional version takes place). Throughout these early scenes we can see an unusual degree of intensity in Lee’s expressions hinting that he may not be as he first appears. Driscoll is angry at some of the students disinterest but appreciative of one bright student, Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson, an actress with only a handful of credits to her name) who plans to travel to Whitewood, Mass. on her own to carry out further investigation of the case. Driscoll recommends a hotel for her to stay in, the Raven’s Inn. On the journey there, close to Whitewood at a fork in the road she picks up a stranger who helps show her the way; he identifies himself as Jethrow Keane. Keane is played by a wonderful and a sadly under-used Shakesperean actor called Valentine Dyall who has the perfect John Carradine-like stoney face with a sonorous voice – perfect for gothic horror. When they arrive at foggy Whitewood Nan’s passenger mysteriously disappears. At the inn Nan is greeted by the proprieter of the inn, a Mrs. Newless (we never meet Mr. Newless). If she looks familiar, that is because this is also Ms. Jessel who we previously met as Elizabeth Selwyn. Jessel has the perfect angled features for the role of a witch. What is clear from the introduction to all the characters so far is the way veteran cinematographer Desmond Dickinson shoots his subjects using a mixture of shadows and lenses very well. This is also the case when Nan goes to the local church where Nan speaks to the elderly blind Reverend Russell (Norman Macowan) who warns her of danger. The few locals Nan meets are strange zombie-like figures who look at her with sinister blankness. The one exception is the reverend’s granddaughter (Betta St. John) who runs a local antique shop and has recently moved there. She lends Nan a book on witchcraft, but it soon becomes clear that her life is in danger.

The City of the Dead was released in the US as Horror Hotel, the title change probably cashing-in on the Bates Motel from Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. (The American version is included on the disc but if this is your first viewing I would stick with the original British release.) In the UK Psycho and City of the Dead were both released in September 1960, but the shorter and cut Horror Hotel was not released until 1962. Much was made of the similarities between Psycho and City of the Dead (ths is covered in interviews with several participants on the disc). This link is in all probabililty a misdirection as City of the Dead began shooting before Psycho and any similarities are in all probability coincidental. Never the less there are some, dare I say zeitgeist themes present in the film. The film is almost exclusively studio bound, shot at Shepperton Studios with an almost comical if effective overuse of a fog effect present through most of the film. Some scenes also bare some similarity to Mario Bava’s cult Italian horror, Black Sunday (also made in 1960). Most significantly in the history of British horror cinema this film marks the start of an acknowledged rival to the Hammer horror films and a segue between the maturer gothic horror of the earlier Hammer horror films and aiming for a younger teenage market. Two of the film’s producers were Max J. Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky, two Americans who had by this time settled in Britain having made a couple rock and roll films in the USA that included performances from the likes of Chuck Berry and Fats Domino. After City of the Dead Messrs Subotsky and Rosenberg would go on to form Amicus Productions in 1962, the acknowledged rival to Hammer Films, although the style here is quite different to the Amicus films. Another aspect of the film is the emergence of teenage protagonists. In the US Roger Corman had been making many teencentric exploitation B movies which have included sci-fi, horror, dragstrip movies and other teen themed movies in which teenagers were the heroes defeating evil or alien invaders (although not Roger Corman, 1957’s Invasion of the Saucer Men is a key example). The scene between the opening Puritan witch burning and the next scene in the classroom jars a little with the focus shifting to a teen conversation after Lee’s Professor Driscoll demonstrates his disapproval of the disinterested teens.

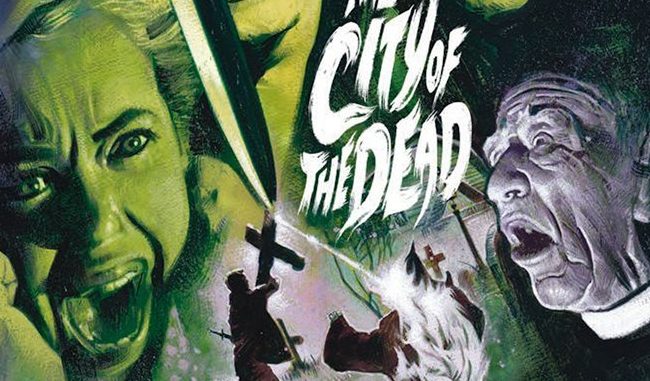

The atmosphere for City of the Dead, considering that this is a B picture is outstanding which looks even more stunning with its 2K transfer from the original negative. Christopher Lee, not yet the star he was to become either in horror or elsewhere was beginning to break away from the Hammer stereotype – he was still playing support to Peter Cushing or cast as the monster. Yet by 1959-1960 he started to appear in international films and was adding some genuine class to B pictures made by small independent or minor studios, as he would continue to do throughout the 1960s. It is also true that Lee (and Cushing) would bring some style and class to the most terrible films. This is not one of those terrible films, for despite its low budget from an inexperienced director and an independent studio (Vulcan Films, although released by Britannia Films and British Lion) this film showed what can be achieved on a low budget. The extras on the disc, as expected from Arrow Video are plentiful. As well as the very attractive cover artwork there are plenty of wonderful extras including an interview with director John Llewelyn Moxey, who would mostly go on to direct on TV rather than features and an as always fascinating archived interview with Christopher Lee who candidly speaks about the problems within the British film industry. There are three commentary tracks on the disc. As well as one from Moxey, there is one from Lee who adds his own recollections on the film as well as Christopher Lee and classic horror film expert Jonathan Rigby who packs the entire film with his vast knowledge on the film, the cast and crew and horror films at the time. A long awaited and superb package from Arrow Video.

Chris Hick