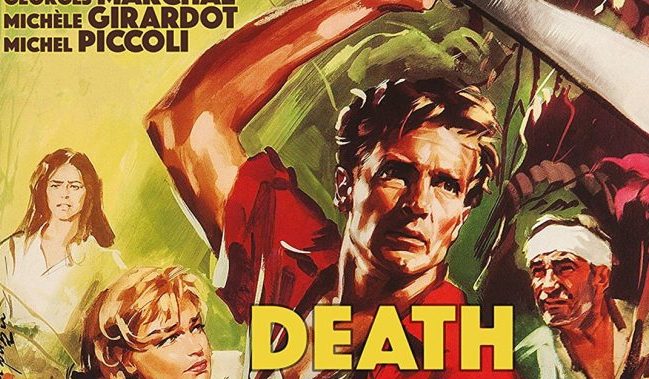

Death in the Garden (1956) Blu-ray Review

Both ends of Luis Buñuel’s long career are well written about. There are his early films and collaborations with fellow Spanish Surrealist, Salvador Dalí: the short Un Chien Andalou (1929) and his first feature, L’Age d’Or (1931) before he was forced into exile in Mexico for many years. In 1967 he made Belle de Jour and for the next 10 years working with his co-screenwriter, Jean-Claude Carrière he made arthouse classic after arthouse classic. Then there is the long stretch in the middle in which most of his films were made in Mexico. Of course there were exceptions and Death in the Garden (La mort en ce jardin) (1956), which is one of three films he made in the 1950s that were French-Mexican co-productions. The other two were That is the Dawn (Cela s’appelle l’aurore) (also 1956) which also starred Georges Marchal and La fièvre monte à El Pao (1959). Death in the Garden is the better known and the best of the three films. It is an action adventure and although does not have those distinct Surrealist elements of his French films from the two ends of his careerbut does have a very interesting narrative structure. There are some very Buñuelian elements in its subtle imagery while the anti-clericism or anti-religiosity is very apparent in the character of Father Lizardi.

Death in the Garden is set in an unnamed South American country bordering Brazil (possibly French Guiana). Unlike in most of Buñuel’s films of this period all the protagonists, particularly in the second half are French ex-pats. There is civil unrest in the country and it would seem that the country is run under fascistic military rule. Many of those working here are opportunists and diamond miners. The soldiers comes in one day and tell the prospectors that they are no longer allowed to work. The prospectors and the workers alike rise up and take up arms against their violent oppressors. One such person is the gruff and rough Chark (played by the now all but forgotten leading French actor, Georges Marchal). He has already upset the elderly French expat Castin by mocking and molesting his pretty mute daughter Maria (Michèle Giradon). In the saloon Chark rests his head for the night but is awoken by the hooker Djin (Simone Signoret) who’s bed he is sleeping in. He pays her to spend the night, but the next day Djin has grassed him to the authorities when he is taken for imprisonment by the army, allegedly for a bank hold-up in another city. Chark is beaten but is offered help by Father Lizardi (Michel Piccoli). Chark escapes and helps with the armed insurrection against the army and eventually must escape from the town along with Djin, Castin and Maria, Father Lizardi and the two-faced Alvaro (Raúl Ramírez). Castin also believes that Djin will open a restaurant with him in Paris. They make their way on a launch down river but when they break down they are forced to make their way through dense jungle to Brazil. With the soldiers in pursuit their position is betrayed by Alvaro who Chark kills. Now it is a matter of survival of the fittest as they fight their way through the dense jungle without provisions.

There are no Surrealist elements in the first half of the film as it mostly deals with the struggles of the workers and fleshes out the characters for us. There is only one scene of absurdity when Chark, arrested and beaten by soldiers is led to a church where Father Lizardi is given a sermon and is beaten to the floor to pray where he is helped this time by Maria. This is a running element, not only in this film but throughout Buñuel’s oeuvre where the ritual of the catholic church is mocked. However, it is the scenes in the jungle where Buñuel’s imagery comes to life. There is one scene in which we jarringly see a nocturnal scene on the Champs Elysees when the car sounds grind down and we realise it is a postcard Castin must put on the fire to keep the fire going in the jungle, representing his longing for France. This highlights not only Castin’s lost hopes, but also that of the entire group. Although he is a support character Piccoli’s priest is among the most interesting as he goes from this conforming character who can only accept the status quo to having to burn pages from his bible to put on the fire and, in a sense makes him more human (during the Spanish Civil War the catholic church had supported the fascists). It is here where the subtlety of Buñuel’s art lies in the way he cleverly shows the inadequacies and farcical nature of the church.

The jungle in the film also represents the chaos in life which the characters must literally fight their way through until the survivors receive redemption at the end of the film. The scene in which Chark finds the downed plane represents their return to the bourgeois trappings of society. The three approximately 30 minute interviews on the disc draw to our attention these and many of the themes Buñuel explores in this film as well as others in his career. The interviews are discussions on the film and Buñuel by Tony Rayns, Buñuel biographer Victor Fuentes and an archived interview with Michel Piccoli.

Chris Hick