The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) Blu-ray Review

When The Sorrow and the Pity was released in 1971 France was not ready for this self-reflective study of itself under the occupation during the Second World War. Many cinemas and French television refused to show it. In an extra on the disc director Marcel Ophuls claims that on its cinema release just 60,000 people saw it, when it was finally shown on French television in 1981 it reached 2 million viewers. The film would also be referenced in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) when Woody takes his date (Diane Keaton) to see it at a movie theatre in New York. Three years after this documentary was released Louis Malle made Lacombe Lucien (1974), his feature about denouncers and the collaborators of a town in Vichy France. That film too received a tirade of criticism in France for daring to besmurch the legacy of France during the Second World War. Some of the more interesting of those interviewed include Wehrmacht officers, such as one interviewed at his daughter’s wedding (!) who remains until the very end of the documentary unrepentant of his and Germany’s role in the war. Elsewhere a farmer talks of his experiences in the resistance and his later imprisonment at the concentration camp of Buchenwald.

At 249 minutes this is a long documentary but one that I found to be enthralling. Split into two parts: ‘The Collapse’ and the ‘The Choice’, the film is mostly focused on the people from Clermont-Ferrand, a town in the Massif-Central, just south of the seat of the Vichy Government during the occupation. The town is ordinary and for many their lives changed little during the occupation. It was also one of the early town’s where the resistance against the German occupiers began. Although there is some archive footage, some of which has rarely been seen, it mostly consists of interviews with some of the town’s inhabitants as well as a couple of German Wehrmacht officers and even some key British players as Foreign Minister during the Second World War, Sir Anthony Eden, as well as Georges Bidault who fought with the resistance before becoming France’s Foreign Minister after the war. Others include a local pharmacist who sits with his children and seemed to have zero role in the war and is merely an observer, as well as a local who talks candidly about why he joined the foreign SS Charlemagne Division.

Part One keeps its attention on the swift Blitzkrieg and the shock defeat of France, while some clearly felt abandoned by the British (Dunkirk is not even mentioned). There does seem to be a collective denial from all these French players who’d rather blame others rather than poor leadership that led to the concession to defeat, the humiliation of France and the amelioration by Marshal Pétain and his active collaboration between the Vichy government that led to French citizens denouncing neighbours, active collaboration from the police and later the rabid round up of France’s Jews that one commentator says went further than the German Nuremberg Laws. Yet in the conclusion Eden says “no nation has the right to sit in judgement for any country that has been through all that”. As Part One ends the French settle down to normalisation.

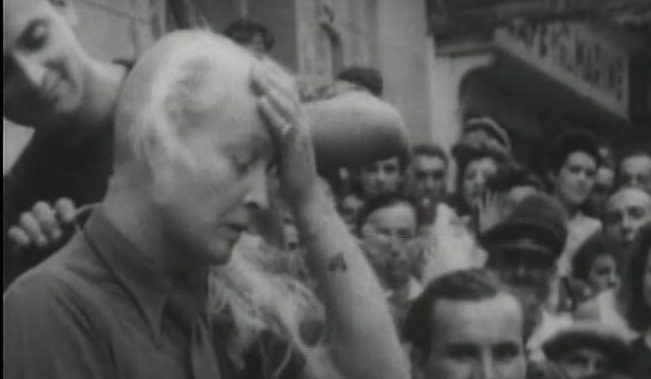

Part Two shows the choices the citizens of Clermont-Ferrand face as a microcosm of the rest of France. While some chose to do nothing other than support Pétain’s puppet government others joined the resistance. Of course the decisions that each person made would have drastic effects on how they would be treated once the war was over. The Jewish community were treated with disdain that equaled the Nazis, while of course many were in denial as to what the fate of the French Jewish community would be once rounded up. Some of the most shocking parts of the second episode are the treatment of women who were deemed, for whatever reason, as collaborators of the Nazis, whether they flirted with or were lovers or prostitutes for the German occupiers. In sham trials they publicly had there heads shaved or were beaten. Summary executions of others also took place. One witness’s testimony led to her imprisonment for years for allegedly denouncing resistors, apparently by a friend. Her denial may or may not be true but it does demonstrate how people in the name of retribution were incarcerated on the scantest of evidence.

Marcel Ophuls was a documentary maker who has a clear sense of irony with regards France’s history. That irony is evident during a screening Q&A with Ophuls made in 2004. Having previous to The Sorrow and the Pity made a lengthy documentary about the 1938 Munich Agreement called Munich, or Peace in Our Time about how the Allies sold Czechoslovakia downstream after the country’s invasion by Hitler, this later documentary caused more than a stir in France and remained controversial there for many years. By the director’s own admission this film was made in the wake of civil unrest in France following the student protests in Paris in May 1968 and the agenda for the film would in all likelihood not have been possible prior to this. Since this film Ophuls has returned to the subject of France’s role in the Second World War with the even lengthier documentary about the SS Gestapo officer Klaus Barbie, also known as ‘The Butcher of Lyon’ in Hotel Terminus (1988).

The Sorrow and the Pity is for many interminably long. That was not my experience. It was instead a gripping and brilliantly directed documentary that surgically analyses it’s subject. In the second part the interviewers push for answers, observations and opinions more than in the first part that makes for riveting viewing. Like the more than 10 hour documentary on the Holocaust, Shoah (1984), Ophuls film relies more on interviews than on footage. Fascinating stuff, even for those with a broad or a lesser knowledge on the subject. Extras also include a Q&A following the films first TV screening in France in 1981.

Chris Hick