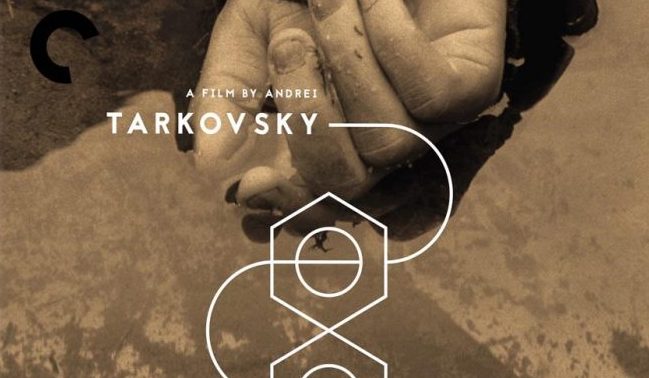

Stalker (1979) Blu-ray Review

Andrei Tarkovsky only made a handful of films including the three he made in the 1970s. Each one of them is a gem, long in length and very intense in detail. The first one of the decade was the pensive science-fiction film Solaris (1972), followed by the Proustian memory piece Mirror (1974) and finally his dystopian post-apocalyptic film, Stalker (1979). On an extra on the disc surviving members of the crew and production all mention Tarkovsky’s fragile ill health and his intensity and intelligence. It also has to be remembered that he was working under the aegis and watchful eye of the Soviet regime.

Stalker has that level of intensity that the above have attributed to Tarkovsky himself, evident in every shot. The story is fairly basic and a little obscure. Originally based off the science-fiction novel of the same name by Arkadiy and Boris Strugatskiy, it is set in a dystopian future in an undetermined country. Most of the opening and closing scenes are filmed in the protagonist’s house and filmed in sepia tone. The Stalker of the title (Alexander Kaidanovsky) lives with his wife who becomes angry at him for going on another job as a guide, taking a professor and a writer to the forbidden ‘Zone’ to a famed room in a building where anyone who enters have their wishes granted. The Zone is a place forbidden for people to go to and is apparently filled with danger and strange effects on the mind. In this place the normal laws of what appear as real don’t count. It would seem that there had at some point been a large meteor strike and those who have entered have never returned, suggesting radioactive poisoning. On an extra on the disc Geoff Dyer, author of ‘Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room’ astutely observes this does seem to predict the ‘real zone’ that became Chernobyl some 14 years later. Stalker journeys with the professor and the writer through the wastelands of abandoned industrial warehouses and derelict buildings as well as a military blockade. The travellers then travel on a rail trolley in a lengthy sequence as they enter the Zone. This is a beautifully filmed sequence, still in sepia with the focus on the three male faces while we hear the rhythmic sound of the trolley travelling over the tracks. Once they are into the (more rural) Zone the film turns to colour. Again there are signs of abandoned industry and traces of human existence, rusting barbed wire, abandoned tanks and half tracks and twisted metal in undergrowth. Stalker orders his clients to follow his lead, not to walk in a straight line and he throws a lead weight wrapped in material to guide the way when they find the abandoned house soaking in water.

There are so many captivating images in this film, the set-up of many were similarly seen in Mirror. Many of these images will remain in the memory for years. The so-called dream sequence in which the camera travels over everyday objects (including a gun and twisted metal) submerged in a few inches of water on a tiled floor played to Eduard Artemyev’s haunting electronic score is one memorable sequence that is similar to Mirror and haunts the imagination. The music of Artemyev is used sparingly in the film but as with his other films through the decade adds to the enduringly haunting images. Throughout, even in the (still) industrial city locations there is a sense of social collapse and decay.

Stalker is not an easy film to watch. It is deliberately slowly paced and at times for many viewers may seem painfully slow. For others the film might be pretentious. Yet for those willing to go on the journey the film will be rewarded and may want to return to the film time and time again. The images will endure like photographs in an art exhibition. The viewer may also seek clues and symbols and come unstuck. An extra on the disc, a discussion and homage to the film by the aforementioned Dyer talks about how he did not like the film when he first saw it on its first release and goes now goes back to it many times. It would be disingenuous to call it science-fiction as it never quite goes down this route. However, the strange perceptions of reality, what the room and the Zone mean and the psychological twists certainly suggest elements of this.

Andrei Tarkovsky is nothing if not an interesting filmmaker. Other extras on the disc give a very Russian sensibility to the way Tarkovsky is viewed. An interview on the disc was one of the last with the second cinematographer brought onto the film, Alexander Knyazhinsky, shot (as with all the extras except the one with Dyer) in 2002 not long before he died. Knyazhinsky, along with the others talk about the difficult shoot on the film, how he was brought after the first DoP was either dismissed or walked off and how after a years filming the whole thing was destroyed in the processing lab leading a very depressed Tarkovsky to re-shoot. Two other extras are with the composer Artemyev who discusses his relationship, or seeming lack of one with Tarkovsky and the set designer who talks about the director’s intensity and attention to detail. Stunningly shot and released in its 2K restoration, the film is one to return to again and again.

Chris Hick