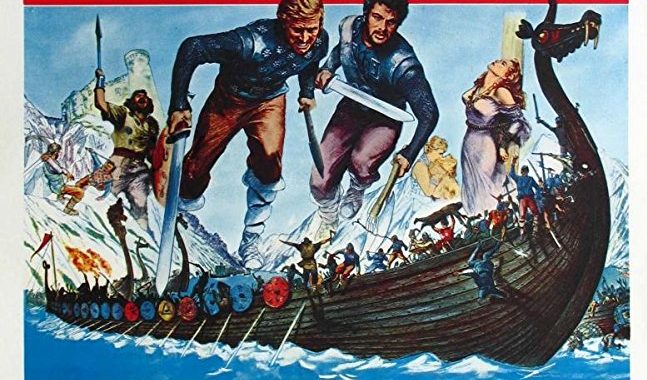

The Vikings (1958) Blu-ray Review

The Vikings was shot in 1957 and released in 1958. Director Richard Fleischer and executive producer Kirk Douglas were keen to make the film as accurate as possible in costume and the life and times and society of the vikings and Anglo-Saxon England, including shooting on location in Norwegian fjords. Made two years before Douglas and co-star Tony Curtis would appear again together in Spartacus, The Vikings did bring in a whole new generation of historical epics. Previous to this many historical epics lacked scope and ambition and were often little more than westerns with suits of armour and with the occasional “thee” or “thou” spoken; and usually shot in California. Not so with The Vikings. The film is gritty with lots of carousing and womanising that makes a Saturday night in Southend look like a WI tea party.

The prologue opens with some background intro to the vikings in the 8th and 9th century with narration by (an uncredited) Orson Welles a tale of how during a viking raid the King of Northumbria is killed by the viking king, Ragnar (Ernest Borgnine) who has also raped the queen. She gives birth to a child who is later kidnapped by vikings as a baby and enslaved. The story jumps forward 20 years with a viking raiding party led by Ragnar returning to their viking fjord village where he is to be greeted by his son, Einar (Douglas). With Ragnar is an English nobleman who had been helping the vikings (James Donald) and Einar falls foul with the nobleman’s slave, Eric (Curtis) who sets a hawk on Einar that tears open his face and Einar also results in the loss of an eye. Einar agrees to save Eric to torture him “over a 1000 nights”, indicating Einar’s fateful Freudian Death Drive. Ragnar and Einar plot, with the aid of the nobleman to go back to Britain and kidnap a bethroathed queen, Morgana (Janet Leigh), whom they wish to use as ransom against the wicked King Aella of Northumbria (Frank Thring). But of course the whole film is leading towards the final conflict between Einar and Eric.

Douglas had previously worked with Fleischer on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and here Douglas often overruled Fleischer in what he wanted on film as Douglas was using his own company (Brynaprod) to make the film through United Artists. As such Douglas is very much the lead actor which creates something of a conflict for the viewer as to who the hero is: the romantic hero played by Curtis or Douglas’s gruff viking, more traditionally should be the villain. This came to the fore during the production itself at Douglas’s behest.

Based off a novel called ‘The Viking’ (in the singular) by Edison Marshall, a work of mostly fiction, it was clearly a well researched film in costume and look: the metal gleems, the jewels sparkle and the rough leather has a 3D quality to it in its gorgeous HD presentation. Although it has a love interest it is not until later in the film that this is given much attention (with Douglas and real-life husband and wife Curtis and Leigh making up the love triangle. It wasn’t long after the film was finished that Leigh fell pregnant with Jamie Lee Curtis). The authenticity of the film is helped too by the locations, with much of the film shot with all the challenges of filming in a Norwegian fjord (as well as by Bavarian and Croatian lakes), interiors in Bavaria Studios, Munich and the final battle in Brittany at Fort La Latte – that finale battle scene looks lush. Aided in this of course, by the fact that it was shot by the foremost location cinematographer, Jack Cardiff.

Other aspects that work well and are apparently authentic include the memorable running of the oars sequence (a stunt Douglas himself volunteered himself for) that works well and of course the infamous plucking of the eye sequence by the hawk. Although this scene is quite violent, bloody and even shocking it is mistakenly remembered by people to have been a very violent and bloody film, but this is the only sequence with any significant amount of blood. The impression of bloody violence is also aided by Douglas’s ‘blind eye’ contact he wears throughout the film. Never the less the action is well staged with some great action sequences, especially the final castle siege against Aella; Thring is great as the villain of the piece and he’d make a good Guy of Gisbourne, even out camping Claude Rains in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). (Thring was a classical actor who often appeared in biblical epics.)

There are a couple of very good extras, each approximately 30 minutes in length. One is an interview with film historian Sheldon Hall, the other has director Fleischer discussing the making of the film with some good production shots.

Chris Hick