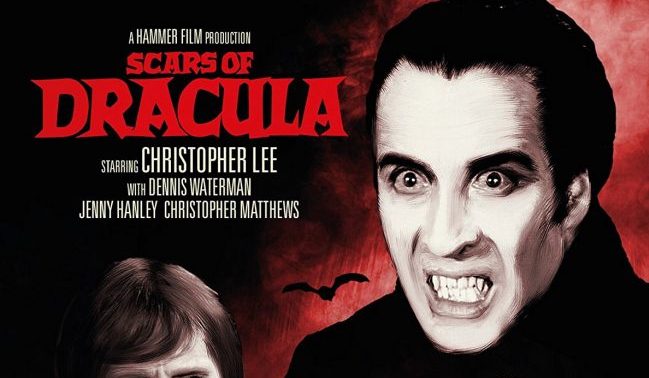

Scars of Dracula (1970) DVD Review

Scars of Dracula (1970) is the 5th of 7 ventures for the Hammer/Christopher Lee Dracula teaming (despite what cultural historian John J. Johnston claims as the 4th in an extra on the disc). It is also both the worst and the goriest of the franchise and, in many senses this film (and the film that it shared a double bill with, Horror of Frankenstein) represents the beginning of the end for the studio that by 1976 barely even existed following the studio’s loss of backing by a major Hollywood studio. This is one of the new round of Hammer Films released by Studiocanal in dual format and is the oldest of the 8, meaning that all the releases represent examples during the downfall. 4 of the films were released at the end of October, another 4 are set for release in January 2018.

Scars of Dracula (1970) is the 5th of 7 ventures for the Hammer/Christopher Lee Dracula teaming (despite what cultural historian John J. Johnston claims as the 4th in an extra on the disc). It is also both the worst and the goriest of the franchise and, in many senses this film (and the film that it shared a double bill with, Horror of Frankenstein) represents the beginning of the end for the studio that by 1976 barely even existed following the studio’s loss of backing by a major Hollywood studio. This is one of the new round of Hammer Films released by Studiocanal in dual format and is the oldest of the 8, meaning that all the releases represent examples during the downfall. 4 of the films were released at the end of October, another 4 are set for release in January 2018.

As a sequel Scars of Dracula totally dismisses the point where the previous more superior film, Taste the Blood of Dracula left off, having been released just 6 months before with the Count left as ashes in an Edwardian English church. Scars of Dracula is set in late 19th century Central Europe and opens with a lengthy prologue beginning with a bat dripping a dead girl’s blood onto some dried red powder representing Dracula’s dry blood, once again regenerating the Count. The discovery of the dead village girl incites torch carrying villagers to burn the castle down. Dracula’s castle is depicted as a dreadful and obvious painting and at best with some wobbly sets. Meanwhile, the Count is safely tucked up in his coffin. When the villagers return home they dicover that all the elderly and women folk have been savaged to death by vampire bats in a particularly gory scene taking advantage of the new BBFC rulings on the ‘X’ certification.

The film then lightens up with the supposed hero of the story, Paul Carlson (played by Christopher Matthews, an actor who only appeared in a couple of films but mostly worked on TV). Playing the role as a kind of Central European playboy doesn’t really work and is one of the most dreadful of all Hammer’s young heroes, along with a completely miscast Dennis Waterman, who is the other young hero, Paul’s brother, Simon. Paul narrowly escapes from the town Burgermeister (played by Benny Hill regular Bob Todd in another miscast role) after being caught red handed after bonking his daughter. He escapes across the border and arrives in at a village inn late at night near Castle Dracula where he is thrown out by the innkeeper (played by Hammer regular, Michael Ripper). He finds shelter in Castle Dracula to be greeted as a guest and is seduced by one of the Count’s captive vampires (Anoushka Hempel), but when the Count catches them the next morning he takes a (obviously rubber) dagger and kills her. (Since when did a vampire die from an ordinary dagger and why did Dracula use a blade when has a perfectly good set of teeth?) Now Paul, as Jonathan Harker was before him, is the Count’s prisoner. Naturally Paul’s brother, Simon and his beautiful fiancee, Sarah (Jenny Hanley) arrive at the castle and are given the same cordial welcome by Dracula. In fact it is only in these two scenes that Dracula actaully speaks.

It’s possible that Scars of Dracula was intended to be a re-launch of the franchise that may have also intended to star a new actor as the Count as Christopher Lee was become increasingly disenchanted in playing the role. If this was the case it fell at the first hurdle. Lee looks paler and whiter than ever before, while, as already mentioned the two young male heroes are very weak. Even Michael Gwynn as the local priest doesn’t seem to have a lot to do. The film is not entirely without merit though. Patrick Troughton is superb as Klove, the Count’s hard done by man servant who seems to enjoy some extreme sado-masochism at the hands of the Count. Troughton had the year before hung up his recorder as the 2nd Doctor Who and had appeared in many films in character parts as well as a successful TV career, but is here one of the best screen man servants of Count Dracula. The other noteworthy part is Hanley’s as the love, or lust interest in the case of the Count. She is delightful in her role, as have been many of Hammer’s female actresses but was sadly dubbed by another actress. On the accompanying documentary on the disc Hanley talks quite candidly about acting with Mr. Lee and how intolerant he was of her giggling when she was being acted by a bat on strings, giving some indication of how serious Lee would take any role and approached it professionally, if devoid of humour.

Directed by competent horror director, Roy Ward Baker he must have been disappointed with the results with possible interference by the studio and a lack of originality, other than of course the famed Dracula crawling up the castle walls sequence that he lifted directly from Bram Stoker’s original novel. This film would be Hammer’s last Dracula film set in a 19th century Central Europe before it made the next two films set in contemporary swinging Chelsea. The one main extra on the disc is well worth a watch as it contains interviews and comments by the likes of such experts on the subject as Jonathan Rigby, Alan Barnes and Kevin Lyons and is directed by Hammer expert, Marcus Hearn.

Chris Hick