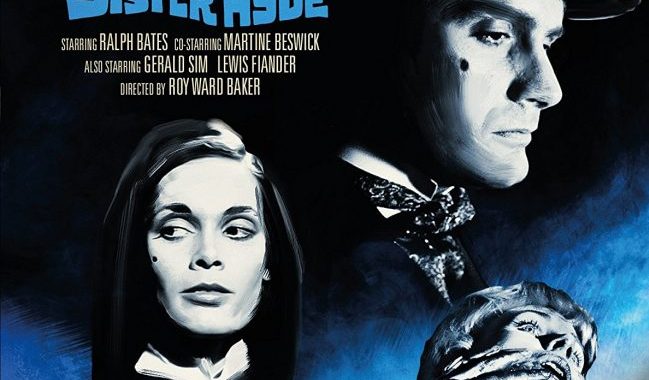

Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) Blu-ray Review

In 1971 Hammer Studios twice broached the subject of Jack the Ripper in a loose mythologizing of the notorious serial killings in Whitechapel at the end of 1888. One was Hands of the Ripper, a more obvious telling of the story without being bogged down with the facts as it fantasies about the Ripper’s daughter continuing his work. The other film was Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde, a grand guignol telling of the classic Robert Louis Stevenson novel that ends up being something of a gothic mash-up of Victorian horror, blending Jack the Ripper, Stevenson’s ‘Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde’ and even grave robbers Burke and Hare. Not to worry that Burke and Hare were operating in Edinburgh earlier in the 19th century. Only Sherlock Holmes seems to be missing as was acknowledged by scriptwriter Brian Clemens.

Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde, despite its laughable conceit is one of the studio’s better efforts in the early 1970s. The film is set in late Victorian Whitechapel, London. In the film Dr. Jekyll is squirreled away in his apartment experimenting with the discovery of an elixor of life. A new family, the Spencer’s have moved in upstairs. The young daughter, Susan (Susan Brodrick) is attracted to Henry Jekyll, but he seems not to notice her. Jekyll’s former colleague, Professor Robertson (Gerald Sim) laughs at his younger friend’s crazy experiments. Jekyll starts to seek hormones and body parts which he collects from corpses. He employs body snatchers Burke and Hare to provide him with bodies. Soon this is not enough and in his own driven madness he starts murdering and hacking up prostitutes in Whitechapel (sound familiar?). He creates the potion he’s been looking for, drinks it and eventually transforms – into a woman (Martine Beswick). The transformation between Henry Jekyll and his alter ego, his ‘sister’ Hyde becomes more regular and begins to take over the obsessive (and equally) wicked Jekyll. Susan, the girl upstairs gets jealous of this femme-fatale, while her brother is attracted to her. The sister half of him now becomes the murderer, diverting suspicion for the murders away from Jekyll.

It would come as little surprise to learn that the idea for the film came from a joke in the Hammer canteen overheard by Hammer Studios boss James Carreras (‘monkey tennis’ anyone?). The result is better than expected and strikes the right balance of being respectful to the material and bordering on some kind of pastiche of Victorian grand guignol. It plays well with the Victorian cliches of foggy Whitechapel streets. There is a deliberate artifice here that looks similar to Oliver! (1968) (the entire film was shot in the studio) with its fog drenched streets and brassy street walkers. The Burke and Hare characters too add some black humour to the proceedings, particularly the Burke character played by Philip Madoc. The script was written by Brian Clemens, who the following year also went on to direct Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter for Hammer here and does a good job with the script. Clemens was also the writer behind such succssful TV shows as ‘The Avengers’ (and ‘The New Avengers’) and ‘The Professionals’.

In an interview Maritine Beswick, in probably her best performance, suggested that the gender swap aspect could have been explored further but is perhaps a little timid in exploring this. The first transformation sequence when a brown tartan dressing gowned Jekyll becomes the sister Hyde is well done and looks as though it was shot in one sequence. What is immediately apparent is how both Bates and Beswick resemble each other that goes beyond the black hair and the facial birthmarks. She/he then begins to explore her body and discovers he/she has boobs (what every man fantasises about, no?). Contrary to popular myth there is not too much nudity in the film compared to many other films in this period from the studio. According to the interview with Beswick on the disc, she was under pressure to show more, but rightly refused, avoiding the film become exploitative. Never the less the film is ably directed by an old horror hand, Roy Ward Baker.

The film, although has the standard early 70s grain, looks good and the colours are particularly lush and deep. The music too sounds good, with David Whitaker’s score sounding great, perfectly matching the fantasy of this piece of Victoriana from the opening credits showing the candle on crimson satin. The accompanying extra on the disc, as with the other Studiocanal releases adds great context.

Chris Hick