Grizzly (1976) Blu-ray Review

Nature goes wild! Again. Or, more accurately, creatures of the wild which have been projected onto our psychology and transformed into creatures a little bigger and a lot more aggressive than they are in reality. Grizzly (1976) followed hot on the heels of one of the best loved creature features of all time and one that fired my own imagination, a gateway film from my childhood – namely Jaws (1975). In Jaws the Great White Shark was some 30 feet and we are told the the grizzly in this film is 15 feet (emphasised throughout that this is a grizzly and not a bear). Jaws, while a huge success was not the first film where nature or rather creatures in nature go wild. One of the first and most influential was Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) in which innocuous fluttery things become aggressive killers. Later there was also Willard (1971) and Ben (1972) about a boy and his killer rat. Other films and animals attacking man that emerged in the 1970s included Frogs (1972), giant rabbits (Night of the Lepus, 1972), Day of the Animals (1973) about chemically imbalanced animals on the rampage (also directed by William Girdler, the director of Grizzly), cockroaches from hell (Bug 1975), big hybrids (Food of the Gods, 1976), sharks again (Mako, Jaws of Death, 1976), Barracuda (1977), ants (Ants! and Empire of the Ants, both 1977), spiders (of course) (Kingdom of the Spiders, 1977), killer whales (Orca, 1977), bees (Killer Bees, 1974 and The Swarm, 1978), an octopus (Tentacles, 1977), piranha fish (Piranha, 1978 and Killer Fish, 1979), Alligator (1980) and even worms (Squirm, 1976). And that’s before, as Calum Waddell reminds us in the sleeve notes before it went totally crazy with Sharknado (2013) and its many imitators and hybrids.

The format for Grizzly runs along the same pattern as Jaws and the comparisons are numerous: campers in the wood are killed and savaged by an aggressive oversized grizzly in a large national park, the sea is substituted by a national park, innocent kids are mauled and killed by the grizzly and there are plenty of severed limbs too. Even the cast of characters are types we saw in Jaws: the police chief is replaced by a park ranger (B movie hunk, Christopher George), a profits before people park supervisor (replacing the mayor), a hunter and a naturalist (Richard Jaeckel). And of course the grizzly is mostly seen in POV which is just as well as by the time we see more of it in the finale and later in the film, he looks rather cute and cuddly. Had this been more of a mainstream success maybe the marketing machine might have produced some cuddly toy version for the kids.

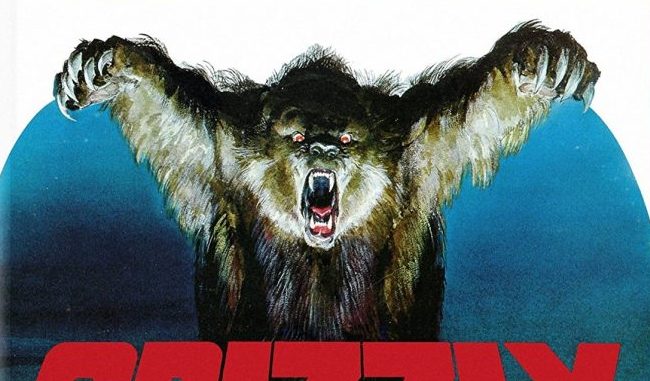

At times the film does look like a TV movie but then the violence turns nasty with severed limbs and blood flying everywhere. Sadly the dialogue is pretty awful and lacks much of the humour in the writing of Jaws; it would have benefitted more from a better rather than a clumsy script. Is it an unqualified classic? No, but the film is hugely enjoyable entertainment if taken for what it is and has since gained something of a cult status which the 88 Films release could help build. Other than a theatrical trailer and a reversible sleeve featuring two different original artwork posters the one extra is a talk on the film by David Del Valle who knew Christoper George and recalls his life as well as talking about the film.

Chris Hick