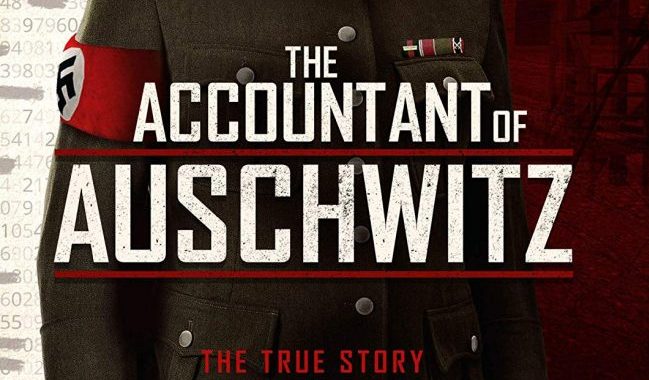

The Accountant of Auschwitz (2017) Review

There have been many documentaries that have dealt with the subject of the Holocaust. Through recent re-releases such as the documentaries by Claude Lanzmann following his epic Shoah (1985) film and follow-up documentaries where we heard the harrowing tales from survivors. Of course since these documentaries were made some 30-40 years ago, most of those survivors have now died. So too have nearly all the perpetrators. On one of those documentaries, ‘Auschwitz: The Nazis and the Final Solution’ made by the BBC, a contributor and an interviewed personality in the documentary was Oskar Gröning, the so-called accountant of Auschwitz. Gröning was quite frank and made no denials in these interviews and admitted how he selected the money and belongings of the victims who were being or had been sent to the gas chambers in the killing factories of Auschwitz. It was this frankness that both directly and indirectly led to him to be tried as a 93-year-old man a few years later and the subject of this documentary.

As already stated, Auschwitz or the Holocaust as a subject has been thoroughly covered, while this documentary looks at the ethics of trying an old man and the problems of Nazi war crime trials since Nuremberg. The documentary puts forward a couple of dilemmas the trials presented. One comes from Benjamin Ferencz, one of the chief prosecutors of the Nuremberg trials and himself in his 90s. He has no pity for Gröning as

Gröning had no pity for those old people and children who were gassed at Auschwitz. Nevertheless, this is a moral question that does trouble many. There is footage of Gröning’s small hometown of Lüneburg where the trial took place. Many of the locals felt sorry that an old man was going through this, others not being able to see the point, as well as those who think it absolutely necessary. Of course this sleepy small small town saw itself in the eye of a media storm as the media and Holocaust deniers all descended on the small town.

The film also looks back at the mistakes of the past, including the Nuremberg trials, as well as those that took place over the following years. Of course many of the ‘A’ list leading Nazis were tried in the first Nuremberg trials and were given lengthy sentences or the death penalty while there were also accusations this was a trial of the victors over the vanquished. Subsequent trials, including those of the heinous Einsatzgruppen (the killing squads that hunted Jews through Eastern Europe) led to many perpetrators receiving small sentences. Over the years Germany was keen to put it’s past behind it while, unlike Nuremberg, they were often being tried by former Nazi judges and lawyers themselves. The problems with these war crime trials have even surfaced with the trials over the wars in the former Yugoslavia, a much more recent war. It is something of a missed opportunity for the film not to highlight the issue of war crimes trials in this and other more recent conflicts and how future trials may broach this dilemma. As one commentator says in this documentary, “there should be no statute of limitations on genocide.”

The best known and most controversial trial in recent years was that of John Demjanjuk, the so-called “Ivan the Terrible”, the Ukranian guard who was alledged to have been a brutal sadist. He was extradited from the United States and whisked off to Israel in 1986 where he faced the death penalty if convicted. His trial collapsed which he gloated over before being re-arrested. Demjanjuk’s American citizenship was later revoked when new evidence came to light and was eventually tried in Germany in 2009. He was tried for crimes against humanity while a guard at the Sobibor Death Camp. During the trial much of the focus was on his alleged ill health and attempts to uncover his fraudulent reported ill health before he eventually died before the trial ended in 2012, aged 91.

This raised the question about putting these old frail men on trial. It looked like history was repeating itself with the Gröning case and history certainly played out that way. One witness and Holocaust survivor said upon seeing Gröning at the trial that she initially felt sorry for the now old man, but his defensive body language and the way he looked across at the survivors that this was the same old Nazi full of arrogance and his anti-Semitism. The documentary attempts to approach the subject from a different angle and this is what sets this film apart with a new set of moral questions, adding to the canon of black history studies, although it does feel in places that more could have been done with it.

Chris Hick