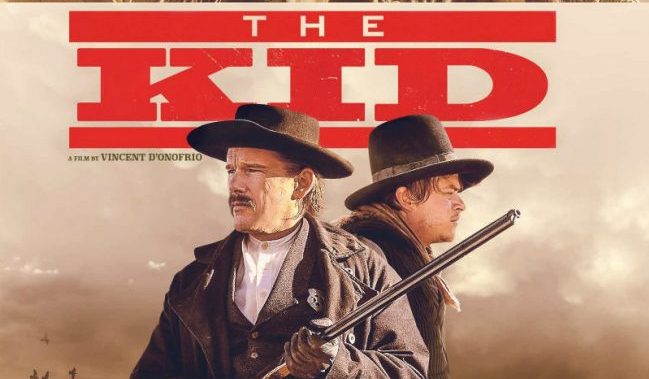

The Kid (2018) Blu-ray Review

Outlaws in Western mythology have a good deal of aura about them, whether it is the gunfight at the OK Corral at Tombstone, Jesse James, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid or Billy the Kid. Hollywood and cinema have been among the leading lights in continuing or maintaining the mythology. The press too helped promote these bad guys into the mythology. All these characters have been given many interpretations in Hollywood. The story of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid was arguably most famously played by James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson in Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 film of these legendary characters, accompanied by the music (and co-starring) Bob Dylan.

Over the past few years the Western, even the smaller low budget ones have had a greater sense of realism than ever before as the sadly little seen The Keeping Room, The Homesman (both 2014) and Hostiles (2017) attest to. This is in contrast to the golden era of the Hollywood Western which created or built a mythology. The film opens with a classic traditional firefight after Rio Cutler (Jake Schur) travels to save his sister Sarah (Leila George) after they’ve escaped from his their violent and dangerous Uncle, Grant Cutler (Chris Pratt). They are kept hostage by a gang of outlaws in a small house and get caught in a gun battle with outlaws. The man the other side of the firefight is legendary lawman, Pat Garrett (a rugged and well cast Ethan Hawke) who is after Billy the Kid (Dane DeHann). Rio and Sarah become witnesses to history and are caught in the middle of the struggle between these two legendary Western characters.

The Kid is directed by actor Vincent D’Onofrio who had been in Men in Black (1998) but most famously played the broken and doomed Private Pyle in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987). He also appears here in his own film as a sheriff. This isn’t his first film as director though, as he started this aspect of his career directing Renee Zellwegger in The Whole Wide World (1996) among a handful of other films. Like many of the aforementioned Westerns, The Kid demonstrates a realist and gritty moodiness that permeates the modern Western. There is an element to the film that is original though and that is the observations of young people to history. This story element has appeared in many Westerns from the fictitious story of Kim Darby witnessing John Wayne’s Rooster Cogburn in True Grit (1969) and the family in Wayne’s last film, The Shootist (1976); both films though said more about a younger people observing the legend that is Wayne himself or another fictitious one is the young boy witnessing and learning from a renowned gunfighter Shane (1953). Of course there is also the young adopted Indian Little Big Man (1970) who witnesses the historical characters of Wild Bill Hickock and General Custer’s demise at the Battle of Little Big Man.

In this sense the children in The Kid and the aforementioned films are not only witnesses to history but assist in writing the legend. Naturally, the film does end with a gunfight although the realism of much of the film does give way to some gunfight excesses veering towards that in Sam Raimi’s The Quick and the Dead (1995). If this was to make a real story more legendary in the eyes of the youngsters, it could have been done more subtly. Nevertheless, The Kid is a worthy addition to the canon of modern Westerns. The only extra on the disc is a Making Of documentary.

Chris Hick