The Holy Mountain (1926) Blu-ray Review

This year is the 100th anniversary of the signing of the liberal and democratic Weimar Republic following the defeat of Germany in the First World War. This led to a flourishing in the arts, science and culture with Germany becoming a very progressive country. In the foreground of all this the country faced hyperinflation and political turmoil throughout much of the decade and became one of the big losers after the Wall Street Crash in 1929. However, not all films were like the arty Metropolis (1926), had the German Expressionism of Warning Shadows (1924) and Nosferatu (1922) or had the humanity of The Last Laugh (1924). There was also an entire genre of films particular to Germany that were known as Berg films. These were popular Alpine films that drew on conservative Bavarian culture. The leading lights of the Berg films were director Dr. Arnold Fanck and Leni Riefenstahl who made The Holy Mountain (1926) with this being the first film of Riefenstahl.

Riefenstahl of course was best known for her Nazi propaganda films, with Triumph of the Will (1934) being the most celebrated, her ground breaking documentary of the 1933 Nuremberg rally and the 1938 film Olympia but before this it was her Berg films. The Holy Mountain is probably the best known of these films but Fanck and Riefenstahl’s films were well liked by the Nazi leadership and continued to be seen when the totalitarian Nazi regime came to power in 1933, unlike many films made during the years of the Weimar Republic. Some read that the traditional Bavarian culture fed into Nazi nationalist ideology and continued to be made and seen in the early days of the Nazis. Ufa, the leading German film company who made the film also embraced their new masters after 1933.

It is essentially a love story driven by big misunderstandings, with the mountains being in someways ‘the other woman’. Riefenstahl, in her film debut, plays Diotima, a dancer who seduces her way to men’s hearts. The dance sequences in the film go some way to explain why the Nazis embraced this particular film, playing very much into their program of

Kraft durch Freude (Strengh Through Joy). There are some strange moves in Riefenstahl as she dances in her flowy Greek style robes showing off her athletic curves. Riefenstahl would repeat this some years later in her own opening dance sequence of the Greek torch bearers in Olympia. She falls in love with Karl (played by that other popular great star of the Berg films, Luis Trenker), an engineer and he takes her up to meet his (conservative) and elderly mother in her mountain cottage. Karl explains his love of skiing and conquering the mountains, enthralling Diotima. One day while Karl is out skiing he witnesses her in what he misinterprets the arms of another man, but can’t make out who it is. Meanwhile, the young man misunderstands Diotima’s friendliness as love.

What is without doubt is that The Holy Mountain is a film with some superb production values and a mixture of studio and location shooting in Switzerland, beautifully shot by Fanck, Hans Schneeberger, Sepp Allgeier and Helmar Lerski. The mountain scenes ratherthan the story are some of the outstanding aspects of this film and given the size of the cameras in the 1920s is a remarkable feat. Meanwhile, the ending and the ice palace of the holy mountain was built as an incredible set on the Ufa stages in Berlin.

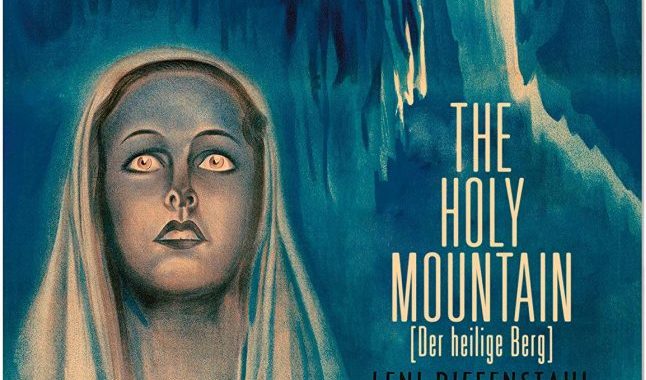

This would not be the last Berg film for Riefenstahl, nor indeed for Fanck with the actress, later director going on to make a further 6 Berg films including The White Hell of Pitz Palu (1929) and The Blue Light (1932) before her more distinguished films as documentary filmmaker during the years of the Third Reich. One significant extra on this Masters of Cinema release by Eureka! (with a wonderful illustrated poster adorning the cover) is the feature length 3 hour documentary, ‘The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl’ which covers her career, the controversy and the later nature documentaries of the director who, as an old lady almost in her 80s. Indeed, this documentary and the Eureka! release does clearly highlight how there were 3 sides to Riefenstahl’s film career: the Berg films, the Nazi propaganda and her nature work, with the middle career still casting a long shadow over her career.

Chris Hick