Donbass (2018) Blu-ray Review

One thing that has regularly appeared with great consistency in European wars are films reflecting on the conflict what the effect has had on the national psyche. A whole new wave of films emerged from the former Yugoslavia and the Balkans during and after the collapse of the former country, each dealing with the allegorical parables of the war. Such films as Srđan Jagović’s Pretty Village, Pretty Flame (1996), Before the Rain (1994) and Grbavica – Esma’s Secret (2006) are all fine examples of this. Equally, the European/Ukranian film Donbass (2018) tackles the subject of identity in the war in a similar fashion. As the Ukranian conflict is both a civil war and one with a foreign actor, Donbass very much references identity. And, like the Balkan Wars it is a European conflict that in certain aspects reflects the worst or most iconic aspects of World War 2.

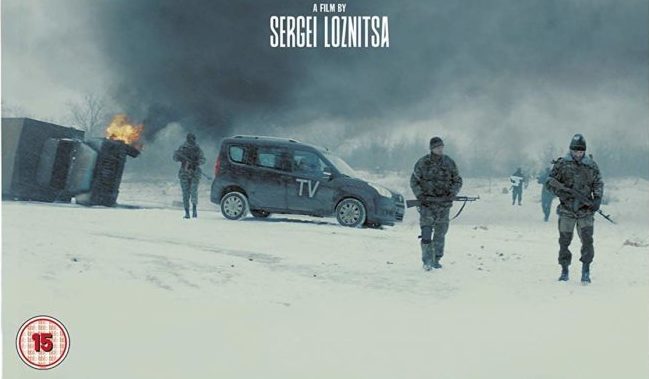

There is not much of a plot to Donbass, but instead a series of loosely connected vignettes with a bookended beginning and end. It starts off with a large older lady being dolled up in a trailer. We later learn that these are actors for hire as witnesses to an atrocity to create some fake news for the Russian backed eastern Ukranian media; Donbass is the name of the region in eastern Ukraine that has been under Russian occupation since March 2014 in which the Russian affiliated Ukranians rose up for alliance with Russia (and indeed the war had been stoked by Russia) and where much of the fighting has since taken place since Russia annexed Crimea. Throughout, there are scenes of mortar attacks, a wedding that seems to become a Nationalist rally, executions and, arguably the best scene, in which a Ukranian soldier is paraded through the streets by two armed militia with a sign around his neck denoting him as a “extermination squad volunteer”. He is tied to a lampost on a main city street where he is initially verbally abused and then physically, at first by track suit wearing youngsters and eventually old people. This scene gradually becomes more violent. This scene especially recalls those during the Second World War where locals and Jews are paraded in the street and given similar punishment. Elsehwere there is also a scene with a flat bed mobile rocket launchers that carry out a devastating attack on a convoy of buses and receives an attack itself. Clearly this demonstrates a breakdown in social norms and niceties.

Of course there are lots of aspects of the film that are only understandable to Ukranians or those with a specialist knowledge: the cossacks, the Nationalist songs, Novorussiya and other coded details. There are also many scenes including the final long and slow drawn out massacre in a trailer and the suspiciously quick arrival of TV crews and emergency services, demonstrating how manipulative the media and the propaganda machine is.

Donbass is a richly layered film deserving of repeat viweing, despite containing some slow and slowly developed scenes. It avoids being heavy handed with any of its own propaganda and leaves it deliberately vague as to whose side who is on which is slowly realised when we start to see Russian flags appearing. Released by Eureka Entertainment on their Montage Pictures sub-label it would be interesting to see more films of this quality emerging from the Ukraine. Directed by prolific director Sergei Loznitsa it also has some great stark cinematography by Romanian Oleg Mutu who perfectly brings out the grey look to the film on the snow and the old imperial buildings.

Chris Hick