Clint Eastwood at 90 years old

Originally published on the Extricate Blogspot.

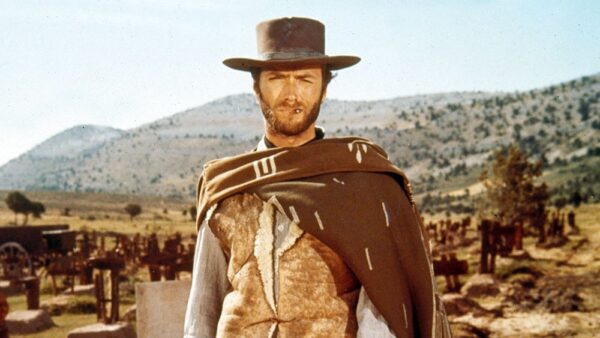

On Sunday 31st May movie icon Clint Eastwood turned 90. Going back more years than I care to remember; okay, for context, going back to the early 1980s when I was a teenager I discovered the wealth of cinema from international to arthouse to national, genre to Hollywood past and present. This coincided with the explosion of video shops popping up everywhere, when Radio Rentals were still in existence and VHS, Betamax and Phillips 2000 were battling for supremacy. This was before Blockbuster monopolised the market and video nasties were not yet called that, but readily available, and not under the counter. During this period there was one actor that stood out among them all – and that was Clint Eastwood. The sequel to Every Which Way But Loose (1977), Any Which You Can (1980) had recently been released in cinemas. Both films were slated by the critics at the time, but it was never really picked up neither then, nor since that both films seemed to reference exploitation cinema which were then earning a second life on the video shelves. In these films Clint had an ape, sorry orangutan companion, a foul mouthed Ma, an inept gang of Hell’s Angels and barroom brawls as well as plenty of country music. During this period every Monday night after the 9 o’clock news BBC1 would often show violent mainstream films from the 1960s and 70s and I would look forward to what was showing. Many of the films shown starred Clint Eastwood. After seeing for the first time such films as the Italian Dollar trilogy (the films that launched Eastwood’s career), Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Joe Kidd (1972), Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974) and The Eiger Sanction (1975) I thought he was the coolest actor around. He grizzled, sneered and ignored mainstream authority and would grow even more grizzled in his later years right up to his most recent performance in The Mule (2018) and in such films as Heartbreak Ridge (1986), Million Dollar Baby (2004) and Gran Torino (2008) among the best examples of Clint at his gruffest.

Nevertheless, Eastwood was no counter-culture anti-authoritarian figure as almost every film since his first starring role back in Hollywood in the western Hang ‘Em High (1968) demonstrated. This film was made to cash in on the success of the so-called ‘Spaghetti Westerns’. In it Eastwood plays a cowboy wrongfully hung by a lynch mob for cattle rustling. He survives the ordeal (saved by Western veteran Ben Johnson) and once he proves his innocence, dons a sheriff’s badge given to him by a hanging judge (Pat Hingle) he goes after those who had done him wrong. His next film was set in psychedelic San Francisco. In Coogan’s Bluff Clint plays an Arizona sheriff who pursues an escaped felon who has gone underground in the San Francisco hippy scene. From these two roles, made three years before he first holstered his Magnum .44 as ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan, Eastwood was honing his establishment figure playing by his own rules. He, like John Wayne, that iconic right-wing cowboy before him, would be critical of the “long hairs” and “punks” in contemporary set films and the wild young wild kids in the westerns. But it is in the iconic Dirty Harry (1971) that the image of Eastwood, going beyond the Man With No Name or enigmatic and quiet gunslinger, would be established. Harry Callahan is a San Francisco police Inspector who is after a serial killer (wonderfully played by Andy Robinson), using his own vigilante methods to get the killer. From the opening scenes in which he shoots a thief, the icon of Dirty Harry Callahan is set. Whether it were the westerns or Dirty Harry, Eastwood’s films were reflecting the violence prevalent in America at the time. Vigilantism became a thing, consolidated in these films and the likes of Michael Winner’s Death Wish, as well as countless Blaxploitation films such as Shaft (1971) or Pam Grier films like Coffy (1973). Eastwood would go on to play Harry Callahan a further four times in Magnum Force (1973), The Enforcer (1975), Sudden Impact (1983) and The Dead Pool (1988). Even in other films in which he plays a cop, such as The Gauntlet (1977) and Tightrope (1984), the character of Dirty Harry never seemed to be too far away.

For many years Clint Eastwood has been responsible for keeping the western alive as a genre when others had dismissed it, or rather when Hollywood decided westerns were no longer a box-office draw. Only a handful of westerns were made in the 1980s, and fewer still in the 1990s. Films such as Young Guns (1988) attempted to make the western appealing to a younger generation featuring the so-called Brat Pack of actors. Although a box-office hit, if not a critical hit, it did not rejuvenate the western as a genre. When Eastwood approached Universal with David Webb Peoples’ script for ‘The William Munny Killings’ he had to fight to get it made, although the project was kept on ice for some years until he felt the time was right. This story became Unforgiven (1992) and earned four Academy Awards including the top three, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Film. Unforgiven had been Eastwood’s first western since Pale Rider (1985) and re-booted his career as a front rank filmmaker, but although he did have recent critical success directing Bird (1988), the biopic of troubled jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker.

Of course it was in Italy that Eastwood first made his name with the Dollar trilogy: A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). With these three films he made in Europe, not only did they launch his career into stardom, but also the career of the Italian director Sergio Leone and the iconic music of Ennio Morricone. This was the birth of the Italian, or Spaghetti Westerns, European films that were shot in Spain, Italy or Yugoslavia to represent Wild West border towns. Over the next 10 years or so hundreds were made. When he returned to Hollywood his first westerns would emulate the Italian Western: Hang ‘Em High, Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970), Joe Kidd (1972) and High Plains Drifter (1973), but with The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) Eastwood changed direction and made the western more realistic, finally moving away from the style of the Italian western. Josey Wales was also made at a time when very few westerns were being made. With his next westerns, Pale Rider and Unforgiven, Eastwood maintained this mythologising of the west as tough, dusty and harsh frontiers.

Of course he is best known as an actor, but over the past few years he has become recognised as a front rank director. He had been influenced by Leone, but when he returned to America to make Hang ‘Em High he agreed to be directed by Ted Post. Post was a mostly routine director whom Eastwood had previously been directed by on ‘Rawhide’, the long running TV western series in which he played Rowdy Yates between 1959-1965. For his next film, Coogan’s Bluff, Clint was directed by Don Siegel, a director who would be the biggest influence on Eastwood becoming a director and would prove to be his mentor. Along with Sam Peckinpah, Siegel was a director who could handle action and violence probably better than any other director at the time. He went on to direct four more of Eastwood’s films: Two Mules for Sister Sara, The Beguiled (1971), Dirty Harry and Escape From Alcatraz (1979). On his return to Hollywood in 1968 Eastwood set up his own company, Malpaso (meaning “bad pass”) and within a couple of years he had autonomy to make what he wanted, with the films usually released through Warner Brothers. This gave him the opportunity to direct the psychological thriller, Play Misty for Me (1971), his first film as director, filmed around his home town of Carmel, California, where he eventually became the town’s Mayor in 1986. It wouldn’t be long before he was making some real bona fide classics such as High Plains Drifter, a classic revenge western. Many have labelled Eastwood the director as a good director, but not up there with the likes of John Ford, William Wyler or Anthony Mann. Films he has helmed, such as Bird, High Plains Drifter, The Outlaw Josey Wales, Unforgiven, Mystic River (2003) and Million Dollar Baby (2004) say otherwise. More recently, with his advancing years, Eastwood is mostly behind the camera rather than in front. This has in no way diminished his career, or his reputation as first flight director as Mystic River, the duo Iwo Jima films, Changeling (2008), Invictus (2009), J. Edgar (2011), American Sniper (2014) and Sully (2016) show, all of which starring the biggest names in Hollywood. Whatever he is thought of as a director, his impeccable instinct as a filmmaker and with his material shows that Eastwood has quality X, an undefinable ability to tune the right film as he showed with Unforgiven and more recently with 15:17 to Paris (2017). This latter film had the audacity to star the three US Marines: Spencer Stone, Anthony Sadler and Alex Skarlatos who were on leave and interrailing around Europe when they happened to be in the right place at the right time in 2015 and apprehended the Morrocan Islamic terrorist, El Khazzani who was about to cause mass casualties on a train and wrestled him to the ground. Months later they were awarded the highest honour in France with the Légion d’honneur. The final shot shows the three men and the British tourist Chris Norman who helped, being awarded the medal by French President Françoise Holland and is depicted in the film. This end is jarring as the events that took place in the film are re-created by Eastwood just a couple of years after the actual events and with the award ceremony is the realisation that these are the real life heroes as we follow their trials and tribulations from childhood to this defining event. Politics aside, it shows Eastwood’s ability to tap into making a film at the right moment, even as an octogenarian.

Of his later career, for my money, Gran Torino (2008) is his best film. Although not the first, nor the last film of his to do so, it is a realisation how an older, grizzled and cynical man overcomes the natural ageing process, his ingrained racism and prejudice to still make a difference. His most recent film is Richard Jewell (2019), another film that deals with terrorism: this time the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Centennial Stadium bombing. Hopefully, although he is now 90-years-old there is still life in the old dog yet. Even if Clint Eastwood makes no more films, his legacy as an actor, an icon and the 38 films he has directed will live on beyond his time on this mortal earth.

Chris Hick