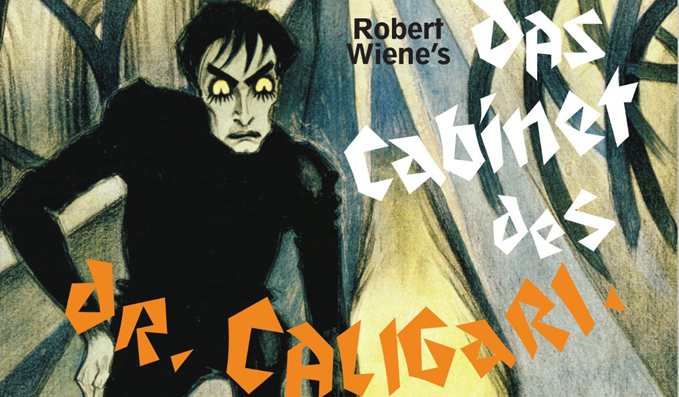

Das Cabinet Des Dr. Caligari Review

Made in 1919, Das Cabinet of Dr. Caligari can perhaps be called the first truly iconic film. This was before other iconic images or films of the silent era: Charlie Chaplin, the profile of Greta Garbo, Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera or Buster Keaton’s incredible stunts. This is all the more remarkable given that the film was made so soon after Germany’s defeat and subsequent humiliation following World War I. Immediately after the war, and before the Versailles drubbing of Germany by the victorious Allies Germany faced the abdication of the Kaiser, a Communist state in Bavaria, communist revolution brutally suppressed by the armed paramilitaries in Berlin, inflation and poverty. This was all before the formation of the liberal Weimar Republic, hyper-inflation and the onset of the Nazis. Many commentators and historians have written that these anxieties come to the fore in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in a story about a sleep walking killer after the film’s authors felt that Germany had been sleepwalking into murder in WWI at the behest of the Kaiser. It is a truly remarkable and unparalleled film that remains as fascinating today as it was on its release. A truly artistic achievement.

Made in 1919, Das Cabinet of Dr. Caligari can perhaps be called the first truly iconic film. This was before other iconic images or films of the silent era: Charlie Chaplin, the profile of Greta Garbo, Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera or Buster Keaton’s incredible stunts. This is all the more remarkable given that the film was made so soon after Germany’s defeat and subsequent humiliation following World War I. Immediately after the war, and before the Versailles drubbing of Germany by the victorious Allies Germany faced the abdication of the Kaiser, a Communist state in Bavaria, communist revolution brutally suppressed by the armed paramilitaries in Berlin, inflation and poverty. This was all before the formation of the liberal Weimar Republic, hyper-inflation and the onset of the Nazis. Many commentators and historians have written that these anxieties come to the fore in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari in a story about a sleep walking killer after the film’s authors felt that Germany had been sleepwalking into murder in WWI at the behest of the Kaiser. It is a truly remarkable and unparalleled film that remains as fascinating today as it was on its release. A truly artistic achievement.

The story opens in an asylum in which a man talks about the story of a German town on the day the fair arrives. One of the exhibitors is an eccentric professorial looking showman called Caligari (Werner Krauss) who promises the crowd that in a coffin on the stage is a man named Cesare, a 23-year-old man who has been a somnambulist sleepwalker for his whole life. Caligari opens the coffin on the stage to reveal Cesare (played by a young Conrad Veidt who would go on to play the German officer in Casablanca opposite Humphrey Bogart), black clad in tights, a white faced zombie-like character. Caligari tells the crowd that Cesare can predict and answer anyones questions from the past, present and future. One man in the crowd asks when he will die. A foolish question indeed. Cesare replies: “before the crack of dawn”. The man is clearly concerned, especially following a series of murders that have occurred in the town. Needless to say just before dawn the shadow of Cesare looms over the man’s bed and he is murdered with Cesare appearing to do Caligari’s bidding.

Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari is an original and unique film with a good twist at the end – probably the first film to have a twist ending refusing to follow normal narrative conventions. It does not, even today appear clichéd or hackneyed and will surprise. It is also a film that is very much a part of the zeitgeist, predicting an age over the next 10 or so years in which a number of bizarre murders and sex crimes occurred (Lustmord), during a period when Germany had a rather troubling obsession with horror and particularly Jack the Ripper. But the film is best remembered for its strange and very artistic sets. Throughout the next decade German cinema was expressionistic in nature and, following the painterly movement of German Expressionism that was perfectly captured through the sets and design of German cinema and theatre in the 1920s. The streets are all jagged, crooked windows, jagged, obtuse and sharply angled rooftops, overhanging street lamps and painted symbols and swirly patterns on the walls. Any sense of realism is suspended while the clothing remains realistic. Although shadows and these Expressionist sets continued to be seen in 1920s German cinema they never again were so Expressionistic or daringly exaggerated. Furthermore the intertitles are better on this release and more Expressionistic than previous prints, including the lettering on the screen where a haunted Caligari has the words “You are Caligari!” printed multiple times over his head.

This film has released in different versions over the years, including from Eureka! who are releasing the film for a limited cinema release from August 29th to the Blu-ray edition a month later. This version is about as definitive as you can get. Using digital 4K cleaning using different prints from around the world the film appears clear and sharp with all the lines, scratches and other imperfections that permeate extant films gone. This new version has been completed by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Munau Stiftung, who had also recently restored F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926) released by Eureka! last month. The restorers were clear to say that they wanted to omit the ageing imperfections but keep those technical problems that would have appeared on the films release through both the filming and printing processes to give the film its authenticity. This does reveal some interesting new views – such as Cesare’s black wig which looks more obviously a wig and gives added expression to Caligari’s make-up. However, the tinted tones of the film: the blues, yellows and oranges look deeper and richer than before and the set designs clearer.

This is a film that should be seen more than once and easily demands multiple viewings. It is unlikely that there will be a more definitive version than this one. There are still a few frames missing from the film causing the film to jump on occasions but the image has never been clearer. For those who have never seen this film before it is highly recommended with this film acting as the foundation to many films that were to follow in the lexicon of cinema.

Chris Hick