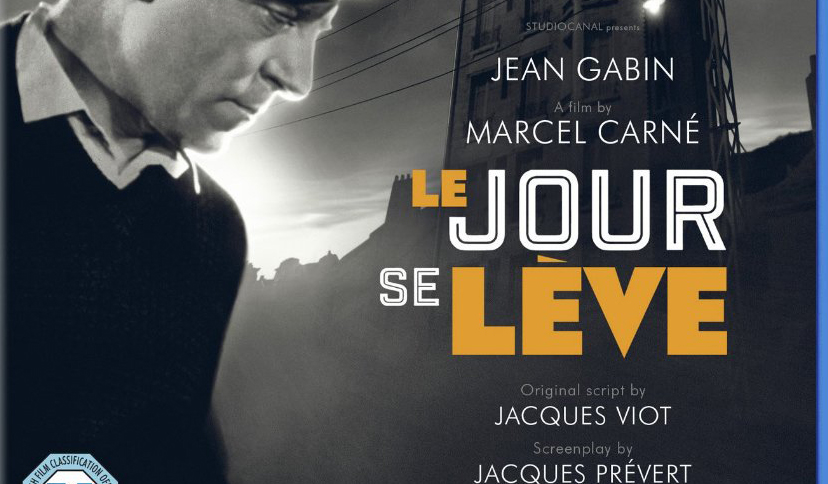

Le Jour Se Lève Blu-ray Review

The 1930s has often labelled as the golden age of French cinema and on viewing a film of this quality it is clear to see why. Many of the best French films of the decade starred the enigmatic Jean Gabin. Were he alive today he would still have the star appeal that would rank alongside many of the enigmatic rugged stars of now. This film ranks alongside two other great Gabin films of the 1930s: La Grande Illusion (1937) and Les Quai des Brumes (1938). The latter film was also directed by Marcel Carné with a script by the poet Jacques Prévert. Both these films are equal in stature in creating a poetic realism with their nocturnal settings and gritty but romantic stories set around an underclass.

The 1930s has often labelled as the golden age of French cinema and on viewing a film of this quality it is clear to see why. Many of the best French films of the decade starred the enigmatic Jean Gabin. Were he alive today he would still have the star appeal that would rank alongside many of the enigmatic rugged stars of now. This film ranks alongside two other great Gabin films of the 1930s: La Grande Illusion (1937) and Les Quai des Brumes (1938). The latter film was also directed by Marcel Carné with a script by the poet Jacques Prévert. Both these films are equal in stature in creating a poetic realism with their nocturnal settings and gritty but romantic stories set around an underclass.

The story of Le Jour Se Lève (roughly translated and originally released in the USA and UK as ‘Daybreak’) centres on working class folk in an unnamed city. It opens with a gunshot and a man stumbling out of a top floor boarding house room and falling dead down the stairs. The man who has shot the as yet unknown individual remains barricaded in his room when the police arrive. A crowd gathers and the police begin a siege beginning with a hail of bullets. François sits in his room apparently disinterested in the hail of bullets coming through and recalls the circumstances that led to the shooting. The rest of the film is a mixture of flashback and present situation. He flashes back to meeting the young and seemingly innocent Françoise (played by the young Jacqueline Laurent, lover of writer Prévert), a flower seller girl whom he falls in love with. She also seems to be involved with the seedy and flash Valentin, a Mountebank (Jules Berry) who runs a show in which dogs do tricks. François traces him to his show and is clearly wracked with jealousy. At the bar he meets Clara, the jaded ex-lover of Valentin and he begins an affair with her. Clara is played by one of the great French actresses of the time, Arletty, an actress with a lot of character on her face. The plot is now leading the viewer to the conclusion that it was the vulgar Valentin who was shot at the beginning. This film really highlights the acting ability of Gabin who was able to express many emotions through his minimal dialogue and subtle facial changes; the consummate movie actor.

Le Jour Se Lève is one of the standout films of the decade and all its artists converge to make a fine classic. Gabin’s facial expressions with Carné’s direction, Prévert’s screenplay along with the cinematography create a perfect example of a movement which became known as Poetic Realism. There is a certain style to these collective films with cinematography being very important as is the subtle use of music. The black and white photography of the rainy cobbled streets, the lighting over Gabin’s eyes and the nocturnal scenes are typical examples of this Poetic Realism. There is also an element of artifice in Poetic Realism such as the rooftops and smoking chimneys that do add to the artiness more than take anything away. The flashback, although it may seem hackneyed now was totally original then and with its strong lighting clearly anticipates Film Noir (itself a French definition) by some three or four years. This was Carné and Prévert’s fourth collaboration together (including the equally brilliant aforementioned Les Quai des Brumes which had also starred Gabin). Fewer screenwriters had as much power or control over films as Prévert who insisted that not one word of his script was to be altered.

There are some fascinating extras on the disc. There is a short doc about the restoration of the film as well as one about the scenes cut by the Vichy Government after Nazi occupation during World War II. This film is very frank with its dialogue; way more than one would expect in a Hollywood film; there are scenes of nudity as well as some frank exchanges between Clara and François where she is inviting him to sleep with her, but he says that he can’t stand make-up. “I don’t wear make-up in bed” is Clara’s reply. Another extra is 90 minute making of documentary that focuses a lot of detail on Prévert and his connections with Surrealism among other things. Many have also read the film as a statement on the Popular Front of France, a left wing politic party which lasted from 1936-1938 before collapsing. Critics have seen parallels between the Popular Front and Gabin’s working-class hero, an everyman pushed to extraordinary circumstances. When the film was made and probably since 1938 there was a sense that war was looming. By the time the film was released and after the Vichy Government became a puppet of the Nazis many scenes were cut before receiving an outright ban. Undoubtedly this is a masterful film that warrants many viewings with its perfect casting, lighting, direction and writing.

Chris Hick