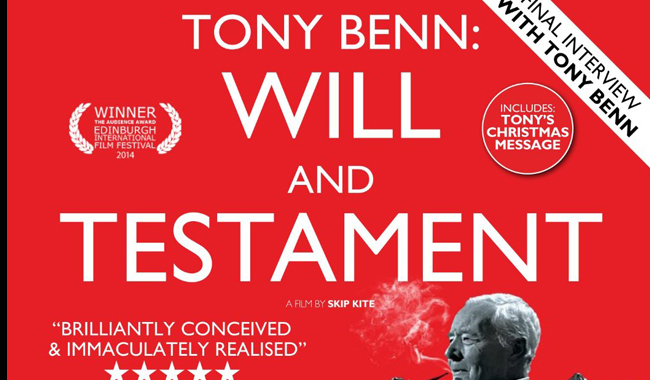

Tony Benn: Will And Testament Review

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014) has variously been described as “the most dangerous man in Britain”, “one of the country’s most extraordinary and controversial MPs” and “a national treasure”. Skip Kite’s documentary Tony Benn: Will and Testament most certainly does not agree with the first statement, but it tries not to simply concede the last either. It is, however, an admiring homage to its subject.

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014) has variously been described as “the most dangerous man in Britain”, “one of the country’s most extraordinary and controversial MPs” and “a national treasure”. Skip Kite’s documentary Tony Benn: Will and Testament most certainly does not agree with the first statement, but it tries not to simply concede the last either. It is, however, an admiring homage to its subject.

Will and Testament – the title makes no secret of whose version of history this is. It is Tony Benn’s reminiscence of his own life, narrated in a series of voice-overs and interviews shot in Benn’s kitchen and on set at Ealing Studios. Supplementing the audio are historical recordings, photographs, and footage of Benn’s private and political life. Far from being a simple history lesson or biography (although it is both), many of the issues that shaped Benn’s thinking, his convictions and politics are increasingly relevant again today.

At the same time, Skip Kite’s documentary is a history of things that Britain values very highly and that are currently under threat. There is obvious nostalgia for a time when people and politicians still remembered what democracy should mean: Benn’s re-election after a hereditary peerage prevented him from continuing in the Commons, and his subsequent campaign to renounce his title which led to the Peerage Act in 1963, are testimony to the power of the people.

The impact of Michel Duvoisin’s soundtrack is obvious not only in quiet, emotional moments but perhaps most so when the narrative reaches the time of the Thatcher government. Benn’s stark criticism of capitalism and New Labour’s endorsement of Thatcherism find visual expression in the Ealing set, the focus of which shifts from an old living room to a space cluttered with visual clues to modern capitalism (a big, golden dollar sign) and protest (tents that signify the occupy movement and anti-war demonstrations). Falling leaves may be a nod to what Benn himself described as “the blazing autumn” of his career outside Westminster. It is obviously Benn’s departure from the ideas of New Labour and his move further to the left that earned him characterisations like “Mad Marxist Werewolf”, “Dictator” or “The Most Dangerous Man in Britain” – quoted in overlaid images of newspaper front pages. Benn describes the press persecution of his family as frightening and the media as “a powerful assassination squad” but it is his characterisation as a “national treasure” he most takes issue with, saying that it makes him sound like a “kindly and harmless old gentleman”. Kind he may be, he acknowledges, a gentleman too, but never harmless.

To politics buffs, any film about the longest serving Labour MP in British politics is likely to sell itself. Film enthusiasts will be interested in the DVD’s extras: a feature-length commentary by director Skip Kite and director of photography Michael Miles gives further insight to the particular choices made about sets, narration and sound. Tony Benn’s very last interview before his death can serve almost as a “deleted scenes”, shedding some additional light on his relationship with his wife to whom Benn proposed within nine days of meeting her. A photo-montage of the images used in the film, tells its narrative in a nutshell of just under four minutes. An impressive piece of documentary film making, Tony Benn: Will And Testament is a respectful and compelling celebration of the life of an inspiring individual. Consistency is often amiss in politics and it is refreshing to see that Benn had it. Whatever anyone’s personal views on Benn, this brilliantly narrated biography of one of the most prominent figures in British politics should not be missed. Especially as it can serve as reminder of what Tony Benn believed democracy should be about: the power of the people to change their situation, and the responsibility that comes to politicians with being “lent” that power by their electorate. A reminder that seems much needed today.

Anne Korn