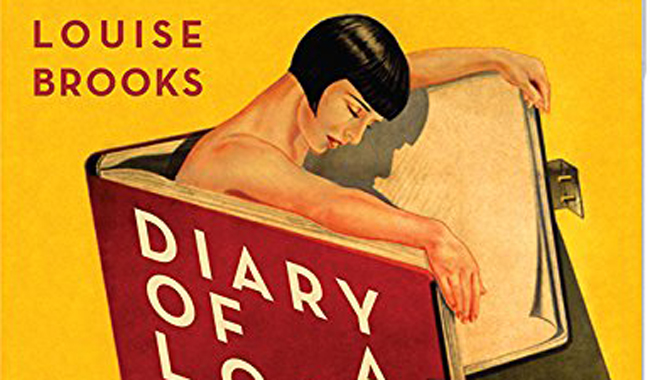

Diary Of A Lost Girl Blu-ray Review

There are icons and there are icons. Louise Brooks is one, or should I say more readily her bobbed hair and perfect profile was iconic. But Louise Brooks was something much more than an iconic actress; she was an actress largely untapped talent. Except, that is the two films she made in Germany directed by the great G.W. Pabst. Pabst recognised the talent of Brooks and invited her out to Germany when the country (or more precisely Berlin) was going through a golden and intense artistic period in a more liberal society (for the time being). Added to this there was a sexual tension between Pabst and Brooks, much like there was between Josef Von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich at about the same time. While Brooks is an icon to many she is still considered to be in the shadow of the likes of Dietrich and Garbo. It is interesting that to be a male who likes Garbo and Dietrich is considered effeminate or certainly appeals to the gay community yet to be a fan of Brooks is quite heterosexual. There is probably to do with roles where she seems more sexually available or even vulnerable.

There are icons and there are icons. Louise Brooks is one, or should I say more readily her bobbed hair and perfect profile was iconic. But Louise Brooks was something much more than an iconic actress; she was an actress largely untapped talent. Except, that is the two films she made in Germany directed by the great G.W. Pabst. Pabst recognised the talent of Brooks and invited her out to Germany when the country (or more precisely Berlin) was going through a golden and intense artistic period in a more liberal society (for the time being). Added to this there was a sexual tension between Pabst and Brooks, much like there was between Josef Von Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich at about the same time. While Brooks is an icon to many she is still considered to be in the shadow of the likes of Dietrich and Garbo. It is interesting that to be a male who likes Garbo and Dietrich is considered effeminate or certainly appeals to the gay community yet to be a fan of Brooks is quite heterosexual. There is probably to do with roles where she seems more sexually available or even vulnerable.

The film opens with an innocent looking Louise Brooks, almost baby doll like in her white confirmation outfit preparing to be confirmed, indicating that she is virginal. The character she plays is called Thymian and that day her family is turned upside down when the housekeeper is sacked after being made pregnant by her father. Later the housekeeper commits suicide and Thymian is seduced and taken advantage of by her father’s assistant, played beautifully by the slimy looking Fritz Rasp (who had previously appeared in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, 1926). She is swooned by him, deflowered and has a baby from him who later dies. In the meantime Thymian is logging the events of her life in her diary which causes her family to catch her out. As a result Thymian is cruelly sent to the care of a despotic boarding school run by a sadistic bald headed man and an old lesbian. She rebels and runs away on them discovering her diary and makes the not so great leap to working in a brothel as a prostitute where she finds a much more honest system.

Pabst at some point turned to Brooks and said to her that she would probably end up like Thymian. How art reflects reality. During the sound period Brooks’s career petered out until she was in support roles in low budget westerns and disappeared into obscurity for many years and rumoured to have become an escort. As artistes the difference between Pabst and Brooks is that Pabst made many great films but for Brooks she only made a couple of truly classic films: Pandora’s Box (1928) and The Diary of a Lost Girl, both of which already mentioned were made by G.W. Pabst. Louise Brooks only made a couple of dozen films from when her career started in 1925 through to the end in the late 1930s but it is really only these films and one underrated Hollywood film, Beggars of Life (1928) that strike out. I have personally seen almost all these films and they are by and large unremarkable. But in both these German films Brooks stands out. This is the Masters of Cinema series and therefore it really is Pabst who puts his stamp on the film reflecting Weimar Germany’s both liberal society and its indictment of the sexual awakening and corruption of an innocent girl. Pabst presents this melodramatic story as poetic realism, not too dissimilar to what was going on in France in the 1930s. The beauty of Pabst’s work also lies with the cinematography, here by Sepp Allgeier, who Brooks had an affair with along with Rasp.

The tones of the film are brought out by the multi-national restoration carried out by the Murnau Stifftung as well as the film archives in Montevideo among other places. The opening of the film quite clearly states through inter-titles the difficulty faced as parts of the film, brought in from all over the world were damaged and were restored to seem seamless but of course some parts were better than others. There are also clear indications on the film that some frames are still missing with some jump cuts. Overall, given the limitations the transfer is very good despite some obvious differences in the quality of grain on the film. On Blu-ray it is of course clearer but also, as usual points out some of the films shortfalls such as the small plaster on Louise Brooks’ neck where she had a small wart removed on Pabst’s instructions.

The one extra on the disc includes a wonderful David Cairns written pictorial essay which at 11 minutes gives an excellent contextual narrative to the film and its relationship with Brooks and Pabst. The viewer is left not feeling cheated or that there could have been more and instead gives a concise context to The Diary of a Lost Girl. Also included is the usual wonderful booklet to add to the package.

Chris Hick