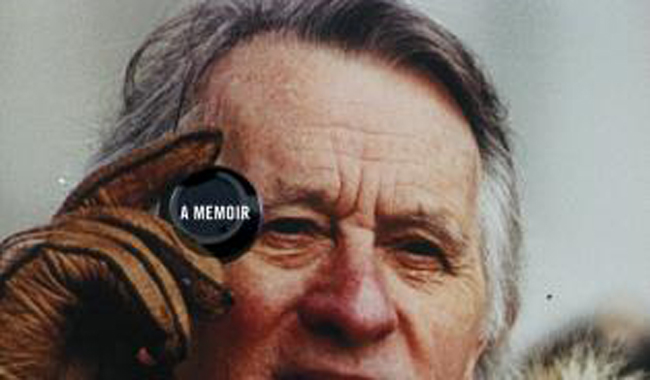

Freddie Francis: The Straight Story From Moby Dick to Glory

Author: Freddie Francis with Tony Dalton.

Sadly Freddie Francis, in many ways a British institution passed away in 2007. Francis had three careers: between the 1930s and 1960s he made the natural progression from being a camera operator in early British B features to major productions. His second career was in the 1960s and 70s when he became a distinguished director of some classic gothic horror films for Hammer and Amicus which often starred Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing before taking a nose dive with some terrible films in the 1970s. His career was saved by David Lynch who asked him if he would shoot The Elephant Man in 1980 allowing him to embark on a second career as a cinematographer.

Sadly Freddie Francis, in many ways a British institution passed away in 2007. Francis had three careers: between the 1930s and 1960s he made the natural progression from being a camera operator in early British B features to major productions. His second career was in the 1960s and 70s when he became a distinguished director of some classic gothic horror films for Hammer and Amicus which often starred Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing before taking a nose dive with some terrible films in the 1970s. His career was saved by David Lynch who asked him if he would shoot The Elephant Man in 1980 allowing him to embark on a second career as a cinematographer.

Of course as this is mostly an autobiography the book is spoken in Francis’s words and he writes the way he talks. He comes across as a typical English gent, despite his working-class upbringing, coming across not too dissimilar from the likes of those aforementioned horror film stars he regularly directed. He is reservedly honest about those he worked with, whether it is Joan Collins, whom he directed in two portmanteau horror films in the 1970s who he felt was spoilt and was above acting in these films (despite already having appeared in several low budget British horror films) and even with director Edward Zwick, the young whizz kid he worked with on the American Civil War/race war film Glory (1989) which won Francis his second Oscar. Francis thought Zwick saw the veteran cameraman as too old school and not his choice which made for an uncomfortable working relationship in an otherwise rewarding challenge of a film.

Freddie Francis was born into a working-class family in Islington near the Essex Road in 1917 to a hard working if cold mother and an alcoholic father (he died when Freddie was young). The one thing he was grateful for was when she bought him a camera sparking his interest in photography. He was then fortunate to get a job as a clapperboard boy for Quota Quickies for British studios at Elstree. His early years were interrupted by the Second World War where he had an easy ride working at a film processing lab in Wembley. After the war his career progressed quite quickly and he was soon a regular director for John Huston, a Hollywood director who often worked as an independent in Europe. Freddie Francis was responsible for the beautifully garish colouring in Huston’s biopic of Toulouse-Lautrec in Moulin Rouge (1952) and also shot the eccentric Beat the Devil (1953) for Huston with some great anecdotes connected connected with Robert Morley, Humphrey Bogart and the life loving Huston. His career progressed through the 1950s before became associated with the kitchen sink dramas culminating with his first Oscar for Sons and Lovers (1960)

The following year Francis made his first foray into the horror film when he shot the brilliant gothic haunted house chiller, The Innocents (1961) starring Deborah Kerr. Shot in widescreen, Francis was forced to use some innovative techniques and created an atmospheric film with more shocks, albeit subtle, than most films of the period. It was also on this film that the cinematographer met the person who became his third significant other, continuity lady, Pamela Mann. After being asked to complete the work on a couple of minor horror science-fiction films Francis was invited by Hammer to direct Paranoiac (1963), starring Oliver Reed, in what was to be his first of three psychological thriller horror cross-over films for Hammer. He also would go onto make one Frankenstein film and a Dracula film for the studio, starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee respectively. Shortly after this Francis would then go on to make several portmanteau horror films with a company that became a rival to Hammer, Amicus. Amicus was run by a couple of Americans, Milton Subotsky and Max J. Rosenberg who made films that starred many of the Hammer regulars (especially Lee and Cushing) and Francis’s films particularly proved successful.

By the 1970s his films became poor choices and third rate films, but he still attracted big names like Cushing and Hollywood actor Jack Palance, films that did nothing for anyones career (although in his own autobiography Cushing said that he was always grateful to Freddie to give him work and keep him busy following the death of his wife). Francis particularly has less than kind words for Ringo Starr who wanted him to direct Son of Dracula (1974) which starred singer Harry Nilsson as Dracula’s son who wants to be normal (Starr also appears as Merlin). A real horror. Francis thought his career over in a whimper until wunderkind David Lynch invited him to shoot the black and white The Elephant Man. This would be the first of three collaborations and Francis has absolute praise and gratitude to Lynch for giving him the opportunity to revive his career. He would also go on to work for Martin Scorsese on Cape Fear (1992), another great collaboration. Two other directors Freddie Francis also praises are Michael Powell, whom he also collaborated with on several occasions and Robert Mulligan whom he made two films with in the 1980s.

Freddie Francis is known for many either as a cinematographer or as a horror director but he says throughout that this was a term and even a genre he detested but scripts for these kind of films was much to his chagrin all he was offered. Still he made a pretty good career with horror films and there are some films that he was surprisingly proud of such as Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny and Girly (sometimes known simply as Girly, 1969) which was a little seen independent comedy horror about a dysfunctional family but was slated by the critics. Never the less this is an easy and enjoyable read and although for horror fans it may only add a snippet of fresh stories and interest it will no doubt be a good read for them, for film historians and those interested in cinema technique – although he admits there is little technical info here but just enough.

Chris Hick