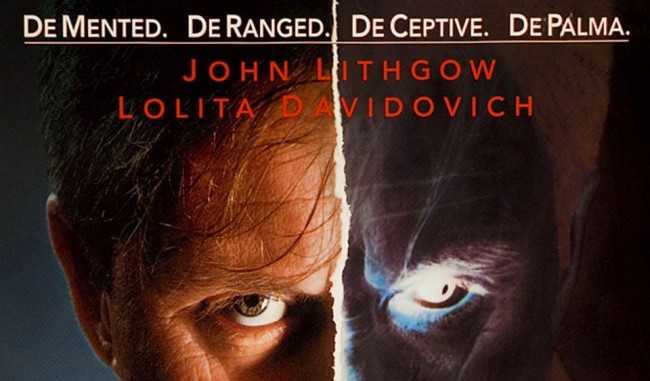

Raising Cain (1992) Blu-ray Review

The trouble with Raising Cain. Brian De Palma’s Raising Cain (1992) has always been problematic in its structure, either with De Palma himself, or with critics and audience alike. In one of the extras on the disc De Palma regular and star John Lithgow discusses the complexity of the plot including the work preparation before filming commenced. This new re-release by Arrow Video faces this challenge head on. Included on the disc is the original theatrical cut and the re-edited version by Dutch editor, Peet Belder Gelderblom, a self-confessed De Palma fan. He re-edited the film with the available material without any cutting or added new material, altering its structure roughly according to the original De Palma script. On viewing the new version in 2012 De Palma was pleased and endorsed it. When it was originally released in 1992, following test screenings De Palma had doubts that the audience would understand his original idea and instead re-cut it into a more chronological narrative. I would have to admit that the re-edited version is preferable and that is the one I will be re-viewing here.

The re-edited version opens with Jenny’s side of the story (in the original theatrical cut the Lithgow multi-character disorder comes out only several minutes in). The film opens in a clock shop where Jenny (Lolita Davidovich) is choosing a gift. Into the shop enters Jack (Steven Bauer), a handsome guy Jenny once had an affair with. She had met him at a hospital where she worked as a doctor, while his wife was dying and began the affair. Her heart is re-awoken on seeing Jack. Shortly after her husband, Carter (John Lithgow) comes in with their 5-year-old daughter, Amy. Carter, himself a child psychologist, on the surface seems the perfect husband and dotes on Amy perhaps at the expense of their marriage. Jenny too seems to have the perfect life. After Jack left his keys in the shop she goes to his hotel to leave a gift and return his keys. They renew their affair but she has some terrible dreams (the difference between the dreams and reality in the narrative allegedly confused viewers on test screenings). Carter learns of the affair and in a surprise moment goes to suffocate her before disposing of her body. Carter also, unknown to Jenny has a multiple personality disorder and this brings out his different personalities: wild brother Cain, his father, Dr. Nix, the child-like character of Josh and a female. The film becomes really twisted at this point and we learn that Carter/Cain is kidnapping children and murdering the mothers for an undisclosed reason, while Carter/Cain try to frame Jack.

De Palma’s films, particularly the thrillers are out there. He is a self-confessed Hitchcock obsessive, but takes away any subtlety while drawing in other film references. Think the excesses of Dressed to Kill (1980) or his Hitchcockian homage to Blow Up, Blow Out (1981). The conclusion of the film is pure De Palma in all its excesses including the music, editing and slow motions. Of course the influences of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) are the most obvious in this film, especially with Lithgow’s Norman Bates like multi-personality disorder, but in true De Palma fashion adds an excess of characters rather than just one. Again, like Psycho there are other elements of Hitchcock’s film drawn in such as the inclusion of a psychiatrist to try and explain Carter’s disorder and to draw the characters out. The other element, in the re-edited version at least focuses on the start with a character for whom the focus will be drawn away from through a traumatic moment. But it is not just Hitchcock De Palma references here but also the father element from Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1959) (itself proto-Hitchcock). The opening scene in the clock shop also raised a lot of questions of curiosity as to what the clock motif means in this scene. Is it a reference to the opening dream sequence in Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries (1957)? De Palma has made no secret on the influence of Hitchcock and Bergman in his films.

As ever with Arrow Video, the extras are plentiful. As well as both the new and original theatrical cut of the film there is a 30 minute documentary, ‘Father’s Day’ (the films original title) about the different versions of the film, an introduction to the new edit by Gelderblom and interviews with the cast, editor and musician (again classic De Palma). This is a film to enjoy not to be taken seriously. While his thrillers might not be his best films, they are his purest and most familiar, and what a fan would expect of De Palma. As John Lithgow says in an interview on the disc, this film is more Brian De Palma than Brian De Palma.

Chris Hick