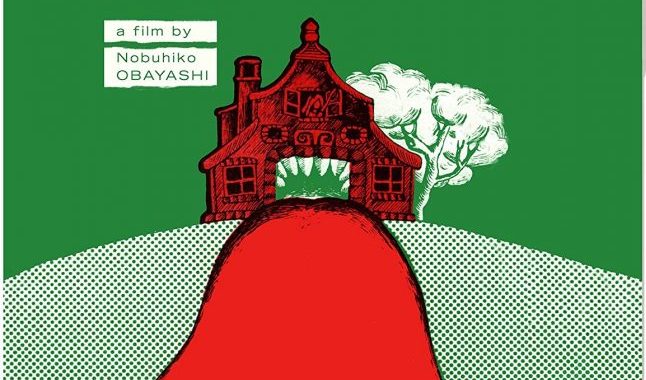

House (1977) Blu-ray Review

If there were a competition for the most bizarre film ever made, surely House (1977) would be a contender. This film certainly doesn’t follow any conventions of narrative cinema. Not only that but the entire mise-en-scène and look of the film is strange and irrational. The tag line for the film was “the cutest nightmare you ever had”, as it blends comedy with gory and supernatural horror and fantasy.

This was the first film for Japanese director Nobuhiko Obayashi who had previously come from making advertisement films. The story centres around Angel (Kimiko Igegami) and her six young school friends: Prof, Melody, Sweet, Mac, Kung-fu and Fantasy (almost like the 7 dwarves!). Angel wants to spend the summer holidays with her father but is disappointed to learn that her widowed father has a new fiancee. Upset, she and her friends decide to go and stay with Angel’s strange aunt at her (rather southern gothic) house in the countryside and journey there by train. From the get go nothing is naturalistic, particularly apparent with the almost cartoon like train journey the girls umdertake. They eventually arrive and are greeted by Angel’s aunt (Yoko Minamida). Although a veteran actress, the aunt looks too young to be playing a disabled Mrs Haversham like old lady in a wheelchair – but this will become clearer why this is later in the film. The aunt also has a big white cat called Snowy that adds presence to the house.

Not long after things start taking a very strange turn. One by one the girls begin to disappear. Melody, while playing the piano in an almost trance state has her fingers bitten off one by one followed by the rest of her limbs before being eaten whole by the piano (Obayashi was asked by Toho if he would make a film like Jaws, 1975 – I guess this was his response). In other scenes Fantasy gets attacked by a disembodied head that bites her on the butt before she kicks it down a well, while Sweet is attacked by a leaping ghost in white sheets (possibly a reference to the ghost film Kuroneko, 1968) before becoming trapped in a grandfather clock. We start to understand that the aunt is becoming younger by dining on the young girl’s blood and limbs.

To describe the film does not do justice to its overhaul strangeness and absurdity. The spfx are animated, and while they might look cartoon-like and amateurish it adds and distances the viewer further from any sense of reality. He not only exploits its lack of reality, but makes a clear statement that this is anti-reality. I would admit on viewing it the first time, the film was irritating, annoying and messy. Viewing it again and understanding what is going on in between its frenetic pace the viewer is urged to suspend any belief and view it as a crazy rollercoaster ride. Not only does it have a comedy style of its own (in a very Japanese brand of humour) but it also seems to be bringing all sorts of horror tropes into the equation. There’s almost a mash-up of horror styles here. On one of the extras on the disc, David Cairns highlights a book he sees on a chair. The book is ‘A Pictorial History of Horror Movies’ by Dennis Gifford, a classic book on horror films that I own and was the point that began my own childhood fascination with horror cinema. Cairns makes the link that the flash of horror images is like the imagery in Obayashi’s film. Other than Cairns’ brilliant contextualising new visual essay for the Eureka Entertainment Masters of Cinema re-release, there are also over 90 minutes of interviews with the cast and crew.

Chris Hick