They Came to a City (1944) Blu-ray Review

By 1944 Britain was already thinking about the aftermath of the Second World War. In June 1944 D-Day took place and with their American Allies were pushing up through Italy under what Churchill called Europe’s ‘tough old gut’. With the exception of a few fight backs by the Germans the Allies were rolling towards Berlin with the inevitable conclusion of the war being clear. Socialist playwright J.B. Priestley wrote his play ‘They Came to a City’ the previous year and as a result of the then current environment added a prologue that would speak to its audience about what sort of future world do we want to live in. The film version was released in August 1944 and the opening shots of the film shows a hill overlooking an industrial town. We hear a young couple, both in armed forces uniforms arguing about what would be an ideal town in a future, post-war world. Along comes a gentleman walker, J.B. Priestley himself, replete with a pipe in his mouth and interupts the young couple and tells them a story of his ideal Utopian city drawing on people from across different societies. One by one we see the 9 people disappear: a char lady from Walthamstow, a very middle-class bickering couple on their way by train to the countryside to the in-laws, Sir George Gedney, who is at the golf course and likes to talk a lot. There is also a mother and daughter, a business banker, a ship’s engineer and a single young woman among the strangers.

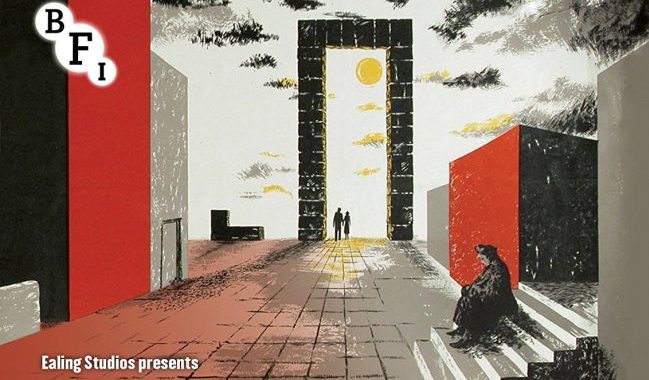

Each one of them walks through a doorway and finds themselves in a misty Neverland. All 9 gather in a mist filled citadel and eventually come together. “This isn’t Walthamstow is it?” asks Sir George (A.E. Matthews), having had his game of golf interrupteded and clearly having never visited that North East part of London. All of them come together, curious at the situation they find themselves in but oddly unperturbed by the mysterious transportation to an apparent alien place. They also see a big door and wonder what’s behind it. Later the door opens and leads down to the city below the citadel fortifications. We never see the city, but each one of them return with different impressions. Sir George wants to leave straight away while Joe, the ship’s engineer wants to stay in what he seems to interpret as a socialist Utopia.

They Came to a City was critically slammed on its release, surprising given its view of seeking a future after the fires of the war years. But in equal measure it is not surprising given both its clear Socialist ideals and also its lack of moving beyond its theatrical origins in an aesthetically uncinematic film; dull as some reviewers disparagingly labelled it. The film follows director Basil Dearden’s previous film in which a variety of people gather at a country inn in The Halfway House, released several months before this film. This is the only time that most socialist of all British playwrights, J.B. Priestley worked with Ealing Studios, a company that had come into its own during the Second World War and one that most assuredly wore its social conscience on its sleeve, following the films coming from the Britain in the 1930s in which everyone spoke with plummy accents. At the last minute Priestley added the prologue and epilogue giving a different perception to the characters in the play/film, making it clearer that the characters are literally figments of the writer’s imagination.

Released by BFI, this is the first time that this Ealing film has been released in the UK on home entertainment. It does seem a little dated today and has made little effort, much like Dearden’s previous film to move away from its theatrical origins and even used most of the same cast from the West End stage production. It includes an early performance from Googie Withers who went on to be an Ealing star in the 1940s gives a feist performance and while the cast do give some strong stand out performances the film otherwise feels a little stiff. Some of this is not helped by the cold, almost fascist architecture of the citadel, leading the viewer to question what’s so great about this place.

As ever with BFI releases they have pushed the boat out with contextual extras, less about the film than the subject of post-war re-generation in Britain. There is a fascinating NFT lecture from 1969 with Michael Balcon who talks about early British cinema and the development of Ealing. In addition there are a series of short films, including Britain at Bay (1940), a propaganda piece relying on archival footage, a documentary directed by Cavalcanti about society and communication in Switzerland and best of all, A City Reborn (1945), a short starring Bill Owen as a soldier returning from the war back to his war damaged city of Coventry and the hopes and aspirations as to how the city will be rebuilt. Other shorts are animated films promoting the creation and benefits of the new idea of the NHS being implemented – one that highlights its importance and how life was before the NHS and another about building New Towns.

Chris Hick