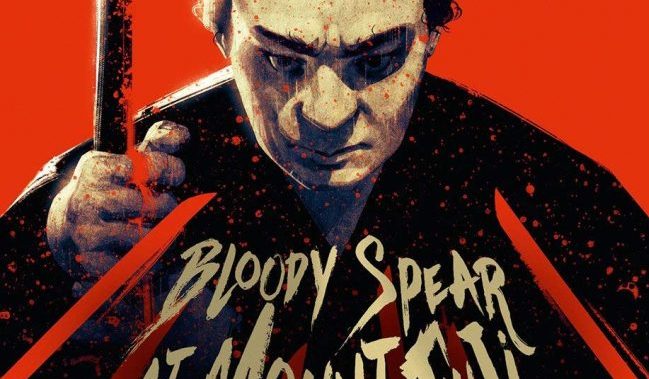

Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955) Blu-ray Review

Don’t let the title, Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955) fool you, this is not a re-release of a Shaw Brothers martial-arts film, but a slow, moody and thoughtful film from post World War II Japan, a golden age in Japanese cinema. This long forgotten classic was directed by Tomu Uchida, a director who doesn’t have the same weight in cinema history as say Yasujiro Ozu, Kenji Mizoguchi or the Master himself and the best known of all Japanese directors, Akira Kurosawa, in the West at any rate. In the West, other than with aficionados, Uchida is virtually unknown and I must admit to not being familiar with this director.

Uchida was a director who was very prolific before the Second World War, having worked for several of the major Japanese studios. During the war his career, like so many others was interrupted, eventually becoming a prisoner of war in Manchuria where he remained a prisoner until 1954. Because of this break, Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji was his first film after an almost 10 year hiatus.

A remake of a 1927 Japanese film, A Journey Full of Sorrow, the film is set in Edo Period Japan, about 300 years ago, this is a judai-geki road movie with Teruo Shimada playing a samurai, Sakawa Kojūrō who is traveling through the countryside and towns on the Tokaido road to Edo with a couple of servants, Genta (Daisuke Katō) and Genpachi (Chiezō Kataoka). He is a kind master, but gets a bit of a dog on when he has had too much sake. On the journey the party come across a full cross-section of society and social types, including an orphan boy who joins them on the journey and aspires to be a spear carrier and a samurai, a traveling singer and her child, a policeman, a group of three peddlers and a prostitute. They also find the road blocked when they come across a group of samurai taking tea and looking at the clouds moving across Mount Fuji in one of the more amusing scenes in the film.

It’s not until the films climax that we get to see the promised action of the title. For the action finale which, Uchida shot it from different angles, including a birds eye view lending the scene more power. With this film, Uchida is presenting us with a slow burning lyrical drama that leads us to this showdown, giving it so much more power than it would otherwise have were there more action. The manner in which the film is constructed puts Uchida up there with likes of other Japanese Master filmmakers (Ozu was a technical adviser on the film) and is in many ways similar to the style of Kurosawa; surprising therefore he is not given the credit he deserves. His magnum opus arguably came with the 3 hour epic, A Fugitive From the Past (1965) which covers Uchida’s war and post war experiences.

On a new makeover release by Arrow Academy, Uchida is given a fresh re-evaluation with 3 featurettes to support the feature. All these extras are archived from previous French releases. The aforementioned extras are a 52 minute interview with Uchida’s son who also worked in cinema, an interview with a Toei Studios publicist and a critical look at Uchida’s oeuvre.

Chris Hick