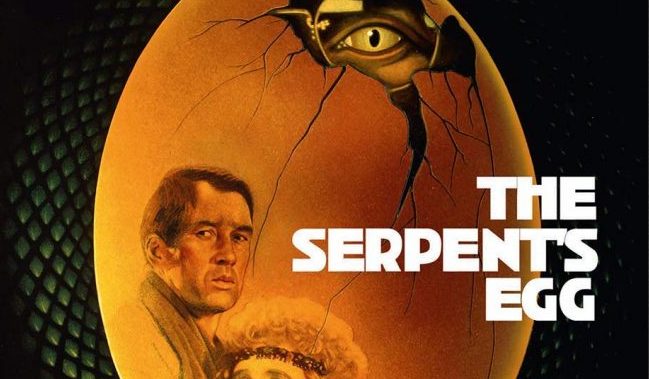

The Serpent’s Egg (1977) Blu-ray Review

Anyone approaching Ingmar Bergman’s The Serpent’s Egg (1977) with Bergman’s oeuvre in mind and expecting Bergmanesque psychological angst will be very disappointed with this film. Approaching with a different perspective will be a different experience for viewers. Author Marc Gervais confirms this in an archival interview extra on this Arrow Academy release, in which he invites the viewer to look at it from the perspective of 1920s Weimar German Expressionism rather than the usual dark night of the soul in many of the Swedish Master’s films. At the time of making The Serpent’s Egg, Bergman was living in self declared exile in Munich, Germany, disappointed and depressed at being hounded for alleged unpaid taxes in his beloved native Sweden, a country his work seemed so entwined with.

How appropriate therefore that the protagonist should be an outsider, an American born Jew called Abel Rosenberg (David Carradine) living in Berlin. The date is November 3rd 1923 and he and his family, former circus performers have recently arrived in Berlin during the period of hyperinflation. Rosenberg does not speak much German and is desperately looking for work. He is struggling with alcohol abuse to numb the pain of his circumstances. He learns that his brother has just committed suicide and sleeps with his sister-in-law, Manuela (Liv Ullmann) who is a cabaret performer. He also starts to learn because he is Jewish as well as an outsider that he is entitled to less than others and cast further out by society. Abel begins to steal from Manuela and take money from others in order to survive.

As the month goes on the crisis in Germany deepens with further anti-Semitic attacks and a deepening political crisis. People here of the Nazis and the plot of a putsch by Hitler in Munich, with the population further attracted to right-wing politics. Abel drifts further into alcohol abuse and becomes further abusive to Manuela.

Bergman continues with his dark themes in The Serpent’s Egg, but moves in a different direction with this film in that, unlike in some of his best known Swedish films, this is not the psychological deconstruction of a couple or a family, but rather of a whole country. The film does feel very set bound, but nevertheless, the director has managed to bring much of the fear that must have been present in Germany in 1923, the darkest days of the post-Great War period until Hitler took power. Suicide, Lustmord, decadence and abuse are all present in the film. Like in many of the director’s films he shows abuse and violence in a very graphic manner, such as when the Nazi thugs between up the Jewish owner of the cabaret in which the violence is captured just off camera, but is none the less still very graphic. Lustmord was very present in the sex crimes taking place in Germany during this period which became evident in films, art and literature at the time. Meanwhile, in one of the most unusual twists of a Bergman film, we see at the films conclusion a proto-Nazi doctor filming experiments of people dying in agony – even himself.

This is a very dark film indeed and not one given a great deal of credit or coverage in the director’s oeuvre; possibly because it was filmed in English and came during his exiled in years in West Germany, his last respected masterpiece had been Scenes From a Marriage (1973). Ullmann particularly demonstrates what an outstanding actress she is as she shows us real emotional pain as the grieving widow caught between the struggles of survival and the abuse at the hands of Abel. Carradine was an unusual choice and not the first, but, as the actor says on the extra, Bergman wanted his mystique (he was TV’s ‘Kung-Fu’ at the time).

Apparently it was not altogether a comfortable experience for Bergman (were any of his films) as he only had Liv and regular cinematographer Sven Nyqvist. The camerawork is very brown and earthy, almost sepia in its tone. I will admit that this was the second time viewing this film and did not particularly like it on the first viewing, but on second with different expectations, it was a much better experience with the director having cleverly depicted the breakdown of the social order in what is otherwise a very un-Bergman like film that pays much homage to Weimar German cinema.

Extras on the disc include archived interviews with Carradine and Ullmann and an interesting talk on the film by writer Barry Forshaw, as well as a commentary by Carradine.

Chris Hick