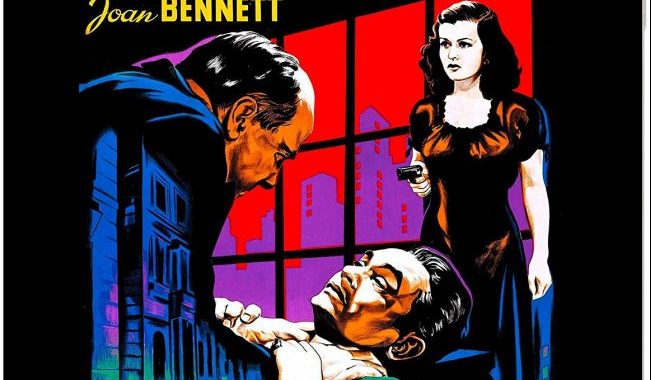

The Woman in the Window (1944) Blu-ray Review

While Eureka Entertainment promote their fantastic range of Weimar German releases, it is sometimes forgotten that there are two great ranges of director Fritz Lang’s oeuvre. There is the German Weimar Period of Destiny (1921), the Mabuse films, Die Niebelungen (1924), Metropolis (1926), Spione (1928), Frau im Mond (1929) and M (1931) (all of which are released by Eureka!) before he fled to France and then Hollywood to escape the Nazi dictatorship (despite being courted by Goebbels). His Hollywood films have been under represented by Eureka, but if the recently released Human Desire (1954) and the now released, The Woman in the Window (1944) are anything to go by that imbalance is starting to be redressed.

The Woman in the Window is one of the classic film noirs of the decade and although films that could be classed as film noir go back to John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon in 1941, it wasn’t until after World War Two that the term was first introduced, unsurprisingly by French film critics. This film was one of the genuine classics and made the same year as arguably the best of them all, Double Indemnity. It was also a film and I will, with some difficulty avoid a spoiler here, but needless to say, while the ending might now seem like a cliche this was the original. I will say no more on that.

This film also moved one of the recognised actors of gangster films, Edward G. Robinson into a maturer performance as a meek husband, something that he would continue to play many times. He would of course return to the tough guy roles he came to be famous for in such films as Huston’s Key Largo (1948). Here Robinson plays a psychology professor Richard Wanley who says goodbye to his loving wife and children as he sees them off at the station as they go on vacation. Interesting that the character is a psychology professor, given that psychoanalysis is one of the tools used to ready film noir. On his way back home, he is entranced by the portrait of a woman in a window display when in a reflection he turns to see a woman (Joan Bennett) strongly resembling the woman in the portrait. He gets chatting to her and she eventually invites him back to her apartment where they are disturbed by her older vulgar and violent lover (Arthur Loft). In an ensuing struggle, the woman, Alice Reed places a stiletto in Wanley’s hand and he stabs the man to death. Between them they plot to dispose of the body.

Wanley coolly takes control of the situation and covers his tracks and even stays close to his friend, a district attorney (Raymond Massey) who is put on to the case and plots to dispatch a blackmailer (a slimey character played by Dan Duryea). With this film, The Woman in the Window quite soon became one of Lang’s most celebrated films and the success of this film was repeated by the same team with Scarlet Street, another film noir thriller, the following year. Indeed Lang would go on to make several noirs. Neither film had the backing of a major studio and were made as indies and therefore making the critical and box-office success all the more remarkable.

Of course there are many elements that go up to make a film noir a film noir. They do not have to be thrillers. Film noirs could be Westerns, horror films or melodramas and each of these there are classic examples. But it is the thriller in which this genre mostly existed. There are many tropes that make up a film noir, but given that there had been no definition of what made a film noir, then the tropes can be fairly loose. The flashback is one trope, as is the femme-fatale, something that Bennett’s character projects, but is far more subtle than Barbara Stanwyck’s duplicitous woman in Double Indemnity.

The only extras on the disc in the latest Eureka Masters of Cinema series is a feature length audio commentary by film historian Imogen Sara Smith, author of ‘In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City’ and a visual essay by David Cairns.

Chris Hick