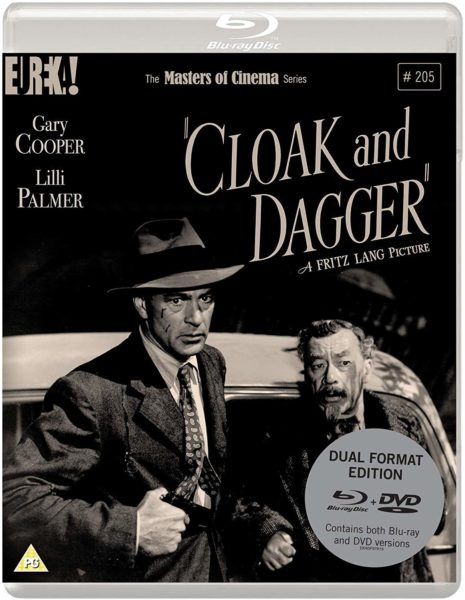

Cloak and Dagger (1946) Blu-ray Review

The story has it that German director Fritz Lang was a favourite of Nazi Reichs Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels. This is surprising given the artistry of Lang’s films, but probably goes back to his two Germanic epic Wagnerian films, Die Niebelungen (both 1924). Lang’s wife, Thea Von Harbou was a supporter of the Nazis, Lang reputedly not. Right up until Lang’s last film in Germany, The Testasment of Dr. Mabuse (1933) the director was making films in the country now ruled over by the Nazis (although the film was not released in West Germany until 1951). Before Goebbel’s could get his grubby mits on him, Lang fled Germany first for France and then Hollywood, making his first film there in 1936.

After a series of very good and diverse films, including a couple of highly acclaimed Westerns, Lang embarked on four war time films that had a film noir style to them with some of the style he brought over from his period of German Expressionism. The first of these films was Man Hunt (1941), loosely based off a true story about a British sniper holidaying in Bavaria before the war plotting to assassinate Hitler. By the time Lang made Hangmen Also Die! (1943) the United States had entered the war. This film was a fictionalised account of the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the Nazi overseer of Czechoslovakia. The third film was Ministry of Fear (1944), a noirish spy film before his post war resistance effort, Cloak and Dagger (1946).

What all these films have in common is that they are based off actual recent stories. Cloak and Dagger was bang up to date, dealing with the Nazi ambitions to build a nuclear bomb while the Americans were building their own. Made after the war, but still dealing with contemporary issues and concerns, Cloak and Dagger was one of the first films to deal directly with the race to build a nuclear bomb, pre-empting the Cold War. The plot sees the Nazis kidnapping nuclear scientists to help them in their ambitions to build a nuclear bomb. Of course in the film the specifics of the science is kept sketchy, as is the issue with many nuclear scientists being Jews. Here Professor Alvah Jesper (Gary Cooper) is approached at Midwest University by an agent of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, a pre-cursor of the CIA) and tells him that one of his former ‘science pin-ups’, Katerin Lodor (Helene Thimig) has made her way across the border to Switzerland where she is recovering in hospital. Jesper makes his way to Switzerland to meet her, but immediately gets the attention of German spies in the country who on more than one occasion attempt to entrap him. Lodor is kidnapped and murdered by Nazi spies setting Jesper on a dangerous mission and a learning curve as an apprentice spy as he undertakes a more dangerous mission to Italy where he joins the Partisans to kidnap another professor who is apparently working collaboratively with his fascist masters. With much risk they take Professor Polda (Vladimir Sokoloff) and try to escape with the professor. In the meantime of course Jesper falls in love with a war hardened partisan girl (played by German actress Lilli Palmer in her first Hollywood role) with an ending completely different from that originally intended.

As ever, Cooper’s performance is understated and the film is deliberately episodic, but this works well for the film. As with Lang’s other films, of this period it is very Hollywood with Max Steiner’s marching and dramatic score, a star performance and wartime romance, but there are many key Lang components in the film too, such as the close-up photography that emphasises violence as well as suspense, making Lang the closest director to Hitchcock as a Master of Suspense (hardly surprising as Hitchcock received his apprenticeship in Germany in the 1920s). A perfect example of this is the fight sequence between Cooper and an enemy agent in a building courtyard, one of the truly impressive set-pieces in the film with its close and finely cut and edited shots while the digetic sound of an accordian is heard on the street outside. It is a long and violent sequence that still looks impressive today.

The team of writers on the film were blacklisted not long after the film with most of the anti-nuclear war elements removed, although there is one speech after Jesper is recruited by the OSS that nuclear weapons will cause future devastation. This seems misplaced given the character in question has in the script been working with Oppenheimer with the speech very post-Hiroshima/Nagasaki (the film of course made after the film was released) in tone. It is an early example of Cold War and not the most celebrated of Lang’s film, but definately an interesting one released in dual format by Eureka Entertainment.

Chris Hick